Chapter 3 JavaScript Basics

Last updated: 2018-11-11 20:44:58

3.1 What is JavaScript?

So far we learned how to define the content (Chapter 1) and style (Chapter 2) of web pages, with HTML and CSS, respectively. We now move to the third major web technology: JavaScript.

JavaScript is a programming language, mostly used to define the interactive behavior of web pages. JavaScript allows you to make web pages more interactive by accessing and modifying the content and markup used in a web page while it is being viewed in the browser. JavaScript, along with HTML and CSS, forms the foundation of modern web browsers and the Internet.

JavaScript is considered, unofficially, to be the most popular programming language in the world (Figure .). Numerous open-source mapping and data visualization libraries are written in JavaScript, including Leaflet, which we use in this book, OpenLayers, D3, and many others. Many commercial services of web mapping also provide a JavaScript API for building web maps with their tools, such as Google Maps JavaScript API, Mapbox-GL-JS and ArcGIS API for JavaScript (more on that in Section 6.4).

3.2 Client-side vs. server-side

When talking about programming for the web, one of the major concepts is the distinction between server-side and client-side.

- The server is the location on the web that serves your website to the rest of the world

- The client is the computer that is accessing that website, requesting information from the server

In server-side programming, we are writing scripts that run on the server. In client-side programming, we are writing scripts that run on the client, that is in the browser.

This book focuses on client-side programming, though we will say a few words on server-side programming in Chapter 5. JavaScript can be used in both server-side and client-side programming, but is primarily a client-side language, working in the browser on the client computer.

As we will see later on, there are two fundamental ways for using JavaScript on the client-side -

- The first is executing scripts when the web page is being loaded, such as scripts that instruct the browser to download data from an external location and display them on the page

- The second is executing scripts in response to user input or interaction with the page, such as performing a calculation and showing the result when the user clicks a button

When JavaScript code is executed in a web page, it can do many different types of things, such as -

- Modify the contents of the page

- Change the appearance of content, or how it is displayed

- Send information to a server

- Get information from the server

In Chapter 3 (this Chapter) we will learn the basic principles of the JavaScript programming language. All of the examples we will see work in isolation, not affecting anything on any web page, yet. In Chapter 4 we will see how to associate our JavaScript code with the web page content, and how to modify the content in response to user input. Then, in Chapters 6-13, we will apply the techniques we learned in the context of web mapping, using JavaScript to create customized web maps and control their behavior.

3.3 JavaScript console

When loading a web page which is associated with one or more scripts, the JavaScript code is automatically interpreted and executed by the browser.

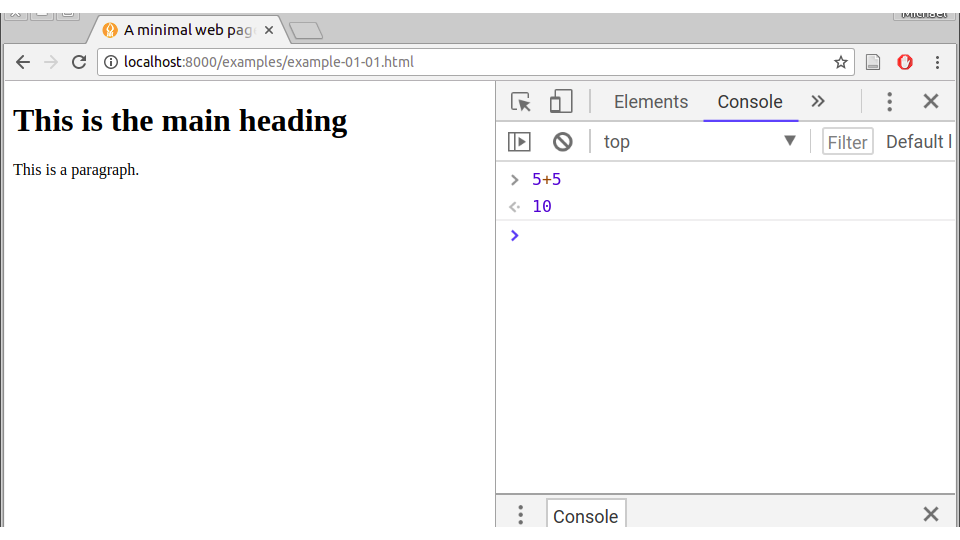

We can also manually interact with the browser’s interpreter using the JavaScript console, or command line, which is built into all modern web browsers. This is useful for experimenting with JavaScript code, such as quickly testing short JavaScript code snippets. This is exactly what we are going to do in this Chapter.

- Open the Chrome browser

- Open the JavaScript console by pressing Ctrl+Shift+J (or opening the Developer tools with F12, then going to the Console tab)

- Type

5+5and press Enter- You have just typed JavaScript expression, which was interpreted and the returned value

10was printed- The expression sent to the interpretor is marked with the

>symbol. The returned value being printed is marked with the<-symbol- Use Ctrl+L to clear the console

Figure 3.1 shows a screenshot of the JavaScript console with the entered expression 5+5 and the response 10.

FIGURE 3.1: JavaScript console in the Chrome browser

The console is basically a way to type code into a computer and get the computers answer back.

In this Chapter, we will be using the console to get familiar with the JavaScript language. We will be typing expressions and examining the computer’s responses. In the following Chapters in this book (Chapters 4-13) instead of typing our JavaScript code will be loaded using the <script> element, either from files or embedded scripts (Section 1.5.3). Nevertheless, will use still use the console when loading scripts, to interactively explore function behavior on currently loaded objects, or interactively debug our script when it contains errors.

3.4 Assignment

Assignment to variables is one of the most important concepts in programming, since it lets us keep previously calculated results in memory for further processing. Variables are containers that hold data values, simple or complex, that can be referred to later in your code.

In JavaScript, variables are defined using the word var, followed by the variable name. For example, the following two expressions define the variables x and y -

var x;

var y;Note that each JavaScript expression should end with ;. Ending statements with semicolon is not strictly required, since statement ending can also be automatically determined by the browser, but it is highly recommended to use ; in order to reduce ambiguity.

Values can be assigned to variables using the assignment operator =.

Assignment can be made during variable definition -

var x = 5;

var y = 6;Or later on -

x = 5;

y = 6;Either way, we have now defined two variables x and y. The values contained in these two variables are 5 and 6, respectively.

In your JavaScript console, to see a current value of a variable, type its name and hit Enter. The current value will be returned and printed.

x; // will return 5The above code uses a JavaScript comment. We already learned to write HTML and CSS comments in the previous two Chapters. In JavaScript -

- Single line comments start with

// - Single or multi-line comments start with

/*and end with*/(like in CSS)

There are several short-hand assignment operators, in addition to the basic assignment operator =.

For example, another commonly used assignment operator is the addition assignment operator +=, which adds a value to a variable.

The following expression uses the addition assignment operator += -

x += 10;This is basically a shortcut for the following assignment -

x = x + 10;More information on assignment operators can be found in the Assignment Operators reference by Mozilla.

3.5 Data types

In the above examples we defined variables holding numeric data. JavaScript variables can also hold other data types. JavaScript data types are divided into two groups -

- Primitive data types

- Objects

Primitive Data Types include the following -

- String - Text characters that are delimited by quotes, for example:

"Hello"or'Hello' - Number - Any integer or floating-point value, for example:

5and-10.2 - Boolean - Logical values,

trueorfalse - Undefined - Specifies that a variable is declared but has no value,

undefined

Objects are basically collections of the primitive data types and/or possibly other objects, plus the special empty object null -

- Array - Multiple variables in a single variable, for example:

["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"] - Object - Collections of

name:valuepairs, for example:{type:"Fiat", model:"500", color:"white"} - Null - Specifies an empty object,

null

Data types in JavaScript are summarized in Table 3.1.

| Group | Data type | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Primitive | String | "Hello" |

| Number | 5 |

|

| Boolean | true |

|

| Undefined | undefined |

|

| Objects | Array | ["Saab", "Volvo"] |

| Object | {type: "Fiat", model: "500"} |

3.5.1 Primitive data types

3.5.1.1 String

Strings are collections of text characters, inside single (') or double (") quotes.

For example, the following expressions define two variables which contain strings, s1 and s2 -

var s1 = 'Hello';

var s2 = "World";Strings can be concatenated using the + operator -

s1 + s2; // Returns "HelloWorld"

s1 + " " + s2; // Returns "Hello World"For more information on strings, see the Strings reference by Mozilla.

3.5.1.2 Number

Numbers can be integers or decimals.

The usual mathematical operators +, -, * and / can be used with numeric variables -

var x = 5, y = 6, z;

z = x + y; // returns 11In this example, we defined two variables x and y and assigned their values (5 and 6). We also defined a third variable z without assigning a value. Note how we defined x, y and z in the same expression, separated by commas; this saves typing the var keyword three time. In the last expression we calculated x+y and assigned the result of that calculation into z.

JavaScript also has increment ++ and decrement -- operators. The increment operator ++ adds one to the current number. The decrement operator -- subtracts one from the current number.

For example -

var x = 5;

x++; // same as: x=x+1; the value of x is now 6

x--; // same as: x=x-1; the value of x is now 5When running the last two expressions, you will see 5 and 6 (not 6 and 5) printed in the console, respectively. This is because the increment ++ and decrement -- expressions return the current value, before modifying it.

For more information on numbers, see the Numbers and Operators reference by Mozilla.

3.5.1.3 Boolean

Boolean (logical) values are either true or false.

var found = true;

var lost = false;In practice, boolean values are usually created as the result of comparison operators.

For example -

9 >= 10 // returns false

11 > 10 // returns trueJavaScript comparison operators are summarized in Table 3.2.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

== |

Equal to |

=== |

Equal value and equal type |

!= |

Not equal |

!== |

Not equal value or not equal type |

> |

Greater than |

< |

Less than |

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

<= |

Less than or equal to |

You may have noticed there are two versions of the equality (==, ===) and inequality (!=, !==) operators. The difference between them is that the former ones consider just the value, while the latter ones consider both value and type. What do the terms equal value and equal type mean? Consider the following example, where 5 and "5" have equal value (5) but unequal type (number vs. string). Comparing these two values gives different results when using the == and === operators. This is because == considers just the value, while === is more strict and considers both value and type.

"5" == 5 // Returns true

"5" === 5 // Returns falseBoolean values can be combined with logical operators.

&&- AND operator,trueonly if both values aretrue||- OR operator,trueif at least one of the values istrue!- NOT operator,trueif value isfalse

For example -

var x = 6;

var y = 3;

(x < 10 && y > 1); // Returns true

(x == 5 || y == 5); // Returns false

!(x == 5 || y == 5); // Returns trueBoolean values commonly used for flow control, which we learn about later on (Section 3.9).

3.5.1.4 Undefined

Undefined (undefined) means a variable has been declared but has not yet been assigned a value yet.

var x;

x; // Returns undefined3.5.2 Objects

3.5.2.1 Array

JavaScript arrays are used to store an ordered set of values in a single variable.

The values are assigned to the array inside a pair of square brackets ([ and ]), and each value is separated by a comma (,).

var a = []; // empty array

var b = [1, 3, 5]; // array with three elementsArray items can be accessed using the brackets ([) along with a numeric index. Note that index position in JavaScript starts at 0. (This is similar to Python, but different from R where position starts at 1.)

For example -

b[0]; // Returns 1

b[1]; // Returns 3

b[2]; // Returns 5An array can composed of different types of values, though this is rarely useful -

var c = ["hello", 10, undefined];An array element can also be an array, or an object (see below). For example, an array of arrays can be thought of as a multi-dimensional array -

var d = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]];To access an element inside a multi-dimensional array we can combine several array access operations -

d[2][1]; // Returns 8Note that with d[2] we are accessing the element in position 2 of d, which is [7, 8, 9]. This is the third element of d, since, as you remember, JavaScript index positions start at 0. Then, with d[2][1] we are accessing the second element of [7, 8, 9], which gives us the final value of 8.

For more information on arrays, see the Arrays article by Mozilla.

3.5.2.2 Objects

JavaScript objects are collections of named values. (This is comparable, for example, to dictionaries in Python or lists in R.)

An object can be defined using curly braces ({ and }). Inside the braces, there is a list of name:value pairs, separated by commas ,.

For example -

var person = {

firstname : "John",

lastname : "Smith",

age : 50,

eyecolor : "blue"

};The above expression defines an object named person. This object is composed of four named values, separated by comma. Each named value is composed of a name (such as firstname) and a value (such as "John"), separated by :.

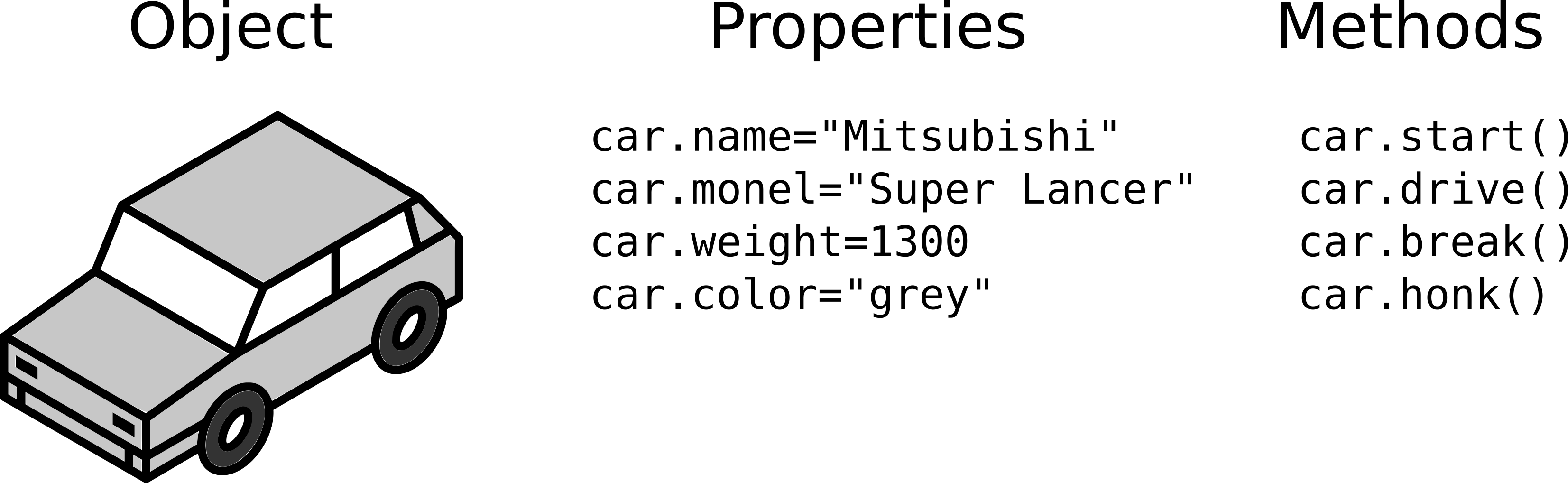

The named values are also called object properties. For example, the above object has four properties: firstname, lastname, age and eyecolor. The values can be of any data type, including primitive data types (as in the above example, "John", "Smith", 50, "blue"), arrays and other objects. They can also be functions, in which case the respective property is also known as a method (Section 3.7).

Objects are fundamental to JavaScript and almost everything we work with in JavaScript is an object. The rationale of an object is to bind related data and/or functionality into a single collection. The collection usually consists of several variables and functions - which are called properties and methods when they are inside objects, respectively.

A JavaScript object is comparable to a real-life object. For example, a car can be thought of as an object (Figure 3.2). The car has properties like weight and color that are set to certain values, and it has methods, like starting and stopping.

FIGURE 3.2: A JavaScript object has properties and methods, just like a real-life object

Object properties can be accessed using either of the following two methods -

- The dot notation (

.) - The bracket notation (

[)

In both cases we need to specify the object name and the property/method name.

For example, getting the person properties using the dot notation -

person.firstname; // Returns "John"

person.age; // Returns 50

person.firstname + " is " + person.age + " years old.";

- What do you think will be returned by the third of the above expressions?

- Create the

personsobject in the console and run the expression to check your answer

The same thing can be accomplished with the bracket notation as follows -

person["firstname"]; // Returns "John"

person["age"]; // Returns 50

person["firstname"] + " is " + person["age"] + " years old.";As shown above, when using the bracket notation property names are specified as strings. This means the dot notation is shorter, but the bracket notation is useful when the property name is specified with a variable -

var property = "firstname";

person[property]; // This works

person.property; // This doesn't workAs we already mentioned, an object property value can be another object or an array rather than a value of a primitive data type. For example, we could arrange the person object in a different way -

var person = {

name: {firstname : "John", lastname : "Smith"},

age : 50,

eyeColor : "blue"

};Instead of having a firstname and lastname properties, we now have a name property value which is an object, containing internal firstname and lastname properties.

To access objects within objects, the dot notation can be repeated several times in the same expression. For example -

person.name.firstname; // Returns "John"This is typical syntax that you will see a lot in JavaScript code -

[object1].[object2].[property];

- Note the auto-complete functionality, which can make it easier to interactively construct this type of expressions interactively in the console

- For example, create the

personobject in the console, the start typingperson.orperson.name.to see the auto-complete suggestions

Object properties can also be modified via assignment. For example, we can change the person name from "John" to "Joe" as follows -

person.name.firstname = "Joe";

person.name.firstname; // Returns "Joe"For more information on objects, see the Objects reference by Mozilla.

3.5.2.3 Null

Null (null) is a special type of object, representing lack of a value.

var object = null;3.5.3 Checking type of variables

The typeof operator can always be used to query the type of variable we are working with.

The following expressions demonstrate the use of typeof for primitive data types -

typeof 1; // Returns "number"

typeof "a"; // Returns "string"

typeof false; // Returns "boolean"

typeof undefined; // Returns "undefined"Note that arrays, objects and null values are collectively considered as objects -

typeof {a: 1}; // Returns "object"

typeof [1,5]; // Returns "object"

typeof null; // Returns "object"3.6 Functions

A JavaScript function is a block of code designed to perform a particular task. If different parts of our JavaScript code need to perform the same task, we do not need to repeat the same code block multiple times. Instead, we define a function once, then call it multiple times whenever necessary.

A function is defined with -

- The

functionkeyword - A function name of our choice, such as

multiply - Parameter names separated by commas, inside parentheses

(and), such as(a, b) - The code to be executed by the function, curly brackets

{and}, such as{return a * b;}

The code may contain one or more expressions. One or more of those can contain the return keyword, followed by a value the function returns when executed. When a return expression is reached the function stops, and the value after return is returned by the function. In case there is no return expression in the function code, the function returns undefined.

For example, the following expression defines a function named multiply. The multiply function has two parameters a and b. The function returns the result of a multiplied by b.

// function definition

function multiply(a, b) {

return a * b;

}Once the function is defined, you can execute it with specific arguments. This is known as a function call.

For example, the following expression is a function call of the multiply function (returning 20).

// function call

multiply(4, 5); Note the distinction between parameters and arguments. Function parameters are the names listed in the function definition. Function arguments are the real values passed to the function when it is called. For example, the parameters of the multiply function are a and b. The arguments in the above function call of multiply were 4 and 5.

A function does not necessarily have any parameters at all, and it does not necessarily return any value. For example, here is a function that has no parameters and does not return any value -

function greeting() {

console.log("Hello!");

}The code in the greeting function uses the console.log function, which we have not met until now. The console.log function prints text into the console.

greeting(); // Prints "Hello!" in the consoleThe console.log function is very helpful when experimenting with JavaScript code, and we will use it often. For example, when running a long script we may wish the current value of a variable to be printed out, to monitor its change through our program.

To keep the returned value of a function for future use, we use assignment -

var x;

x = multiply(4, 5);For more information on functions, see the Functions article by Mozilla.

3.7 Methods

When discussing objects (Section 3.5.2.2 above), we mentioned that an object property value can be a function, in which case it is also known as a method.

For example, a method is defined when creating an object, in case the property value is set to a function definition -

var objectName = {

...,

methodName: function() { expressions; }, // method definition

...

}Note that the function is defined a little differently - there is no function name between the function keyword and the list of parameters (). This type of function is called an anonymous function.

Once defined, a method can be accessed just like any other property -

objectName.methodName(); // method accessThe parentheses () at the end of the last expressions imply we are making a function call for the method.

For example, let us define a car object that has several properties with primitive data types, and one method named start -

var car = {

make: "Ford",

model: "Mustang",

year: 2013,

color: "Red",

start: function() {

console.log("Car started!");

}

};Generally, methods define the actions that can be performed on objects. Using the car as an object analogy, the methods might be start, drive, brake, and stop. These are actions the car can perform.

For example, starting the car can be done like this -

car.start(); // Prints "Car started!"As a more relevant example, think of an object representing a layer in an interactive web map (Section 6.6). The layer object may have properties, such as the layer geometry, symbology, etc. The object may also have methods, such as for adding it to or removing it from a given map, adding popup labels to it, exporting its data as another format (such as GeoJSON, see below), and so on.

- Add another method to the

carobject, namedstop, which prints a"Car stopped!"message to the console- Try using the method with

car.stop()

3.7.1 Array methods

In JavaScript, primitive data types and arrays also have several predefined properties and methods, even though they are not objects. (The mechanism which makes this happen is beyond the scope of this book).

In this section, we look into a few useful properties and methods of arrays: length, pop and push.

The length property of an array gives the number of items it has -

var a = [1, 7, [3, 4]];

a.length; // Returns 3

a[2].length // Returns 2The pop and push methods can be used to to remove or to add an item at the end of an array, respectively. The pop() method removes the last element from an array -

var fruits = ["Orange", "Banana", "Mango", "Apple"];

fruits.pop(); // Removes the last element from fruitsNote that the pop method, like many other JavaScript methods, modifies the array itself, rather than creating and returning a modified copy of it. The returned value by the pop() method is in fact the item which was removed. In this case the returned value is "Apple".

The push() method adds a new element at the end of an array -

var fruits = ["Orange", "Banana", "Mango", "Apple"];

fruits.push("Pineapple"); // Adds a new element to fruitsAgain, note that the push method modifies the original array. The returned value, in this case, is the new array length. In this example the returned value is 5.

3.8 Scope

Variable scope is the region of a computer program where that variable is accessible, or “visible”.

In JavaScript there are two types of scope -

- Global scope

- Local scope

Variables declared outside of a function have global scope. All expressions, inside or outside of functions, on the same script can access global variables. Variables defined inside a function have local scope. Local variables are only accessible from expressions inside the same function where they are defined.

In the following code section, carName is a global variable. It can be used inside and outside of the myFunction function -

var carName = "Suzuki";

// code here can use carName

function myFunction() {

// code here can use carName

}Here carName is a local variable. It can only be used inside myFunction, where it was defined -

// code here can *not* use carName

function myFunction() {

var carName = "Suzuki";

// code here can use carName

}If you assign a value to a variable that has not been declared, it will automatically become a global variable. In the following code example, carName is a global variable though the value is assigned inside a function -

// code here can use carName

function myFunction() {

carName = "Suzuki";

// code here can use carName

}It is not recommended to create global variables unless you intend to, since they can conflict (override) other variables with the same name in the global environment.

3.9 Flow control

By default, the expressions our script is composed of are executed in the given order, top to bottom.

This behavior can be modified using flow control expressions. There are two types of flow control expressions: conditionals and loops.

- Conditionals are used to condition code execution based on different criteria

- Loops are used to execute a block of code a number of times

3.9.1 Conditionals

The if conditional is the most commonly used one. It is used to specify that a block of JavaScript code will be executed if a condition is true.

An if conditional is defined as follows -

if (condition) {

// Code to be executed if the condition is true

}For example, the following conditional sets greeting to "Good day" if the hour is less than 18:00 -

if (hour < 18) {

greeting = "Good day";

}The else statement can be added to specify a block of code to be executed if the condition is false -

if (condition) {

// Code to be executed if the condition is true

} else {

// Code to be executed if the condition is false

}For example, the following conditional sets greeting to "Good day" if the hour is less than 18:00, or to "Good evening" otherwise -

if (hour < 18) {

greeting = "Good day";

} else {

greeting = "Good evening";

}Decision trees of any complexity can be created by combining numerous if else expressions. For example, the following set of conditionals defines that if time is less than 10:00, set greeting to "Good morning", if not, but time is less than 18:00, set greeting to "Good day", otherwise set greeting to "Good evening" -

if (hour < 10) {

greeting = "Good morning";

} else {

if (hour < 18) {

greeting = "Good day";

} else {

greeting = "Good evening";

}

}This type of code can be used to create a customized greeting on a website.

As another example, think of the way you can toggle layers on and off in a web map by using an if statement to see whether the layers is visible. If visible is true, hide the layer, and vice versa.

Conditionals can also be used in map symbology. Consider the following example of a function that determines color based on an attribute (Section 8.4). The function uses conditionals to return a color based on the “party” attribute: "red" for Republican, "blue" for Democrat, and "grey" for anything else -

function party_color(p) {

if(p == "Republican") return "red"; else

if(p == "Democrat") return "blue"; else

return "grey";

}Note that in the above example the {} brackets around conditional code blocks are omitted to make the code shorter, which is legal when they consist of a single expression.

- Define

party_colorfunction in the console be pasting the above code- Try running the

party_colorfunction three times, each time with a different argument, to see how you can get all three possible returned values

For more information on conditionals, see the Making decisions in your code — conditionals article by Mozilla.

3.9.2 Loops

Loops are used to execute a piece of code a number of times.

JavaScript supports several types of loops. The most useful kind of loop within the scope of this book is the for loop.

The standard for loop has the following syntax -

for (statement 1; statement 2; statement 3) {

// code block to be executed

}Where -

- Statement 1 is executed once, before the loop starts

- Statement 2 defines the condition to keep running the loop

- Statement 3 is executed each time after the code block executed

For example -

var text = "";

for (var i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

text += "The number is " + i + "<br>";

}From the example above, you can read -

- Statement 1 sets a variable before the loop starts (

var i=0). - Statement 2 defines the condition for the loop to keep running (

i<5must betrue, i.e.imust be less than five). - Statement 3 increases the value of

i(i++) each time the code block in the loop has been executed.

As a result, the code block is executed five times, with i values of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4.

A loop is an alternative to repetitive code. For example, the above for loop is an alternative to the following code section, which gives exactly the same result without using a loop -

var text = "";

text += "The number is " + 0 + "<br>";

text += "The number is " + 1 + "<br>";

text += "The number is " + 2 + "<br>";

text += "The number is " + 3 + "<br>";

text += "The number is " + 4 + "<br>"; Here is another example of a for loop. In this example the code will be executed 1000 times -

for(var i=0; i<1000, i++) {

// code here will run 1000 times

}Since i gets the values of 0, 1, 2, etc., up to 999.

In addition to the standard for loop syntax shown above, there is a syntax to iterate over elements of arrays or objects. In the iterative syntax, instead of the three statements we define the loop with -

for (var i in object) {

// code block to be executed

}Where i is a variable name (of our choice) and object is the object which we iterate over.

In each iteration, i is set to another object element name. In case object is an array, i gets the index values: "0", "1", "2", and so on. In case object is an object, i gets its property names.

For example -

var obj = {a: 12, b: 13, c: 14};

for (var i in obj) {

console.log(i + " " + obj[i]);

}This loop runs three times, once for each property of the object obj. Each time, the i variable gets the next property name of obj. Inside the code block, the current property name (i) and property value (obj[i]) are being printed, so that the following output appears in the console -

a 12

b 13

c 14For the next for loop example, we define an object named directory.

var directory = {

musicians: [

{firstname: "Chuck", lastname: "Berry"},

{firstname: "Ray", lastname: "Charles"},

{firstname: "Buddy", lastname: "Holly"}

]

};This object has just one property, named musicians, which is an array. Each element in the directory.musicians array is an object, with firstname and lastname properties.

Using a for loop we can go over the musicians array, printing the full name of every musician -

for(var i in directory.musicians) {

fname = directory.musicians[i].firstname;

lname = directory.musicians[i].lastname;

console.log(fname + " " + lname);

}This time, since directory.musicians is an array, i gets the array indices "0", "1" and "2". These indices are used to select the current item in the array, with directory.musicians[i].

As a result, the following output is printed in the console -

Chuck Berry

Ray Charles

Buddy HollyFor more information on loops, see the Looping code article by Mozilla.

3.10 JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)

3.10.1 JSON

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) (Bassett 2015) is a data format closely related to JavaScript objects. It is a plain text format, which means that a JSON instance is practically a character string, which can be saved in a plain text file (usually with the .json file extension), in a database or in computer memory. Other well-known plain text data formats are, for instance, CSV and XML.

JSON and JavaScript objects are very similar and easily interchangeable. For that reason, JSON is the most commonly used format for exchanging data between the server and the client in web applications.

The principal difference between JSON and JavaScript objects is as follows -

- A JavaScript object is a data type in the JavaScript environment. A JavaScript object does not make sense outside of the JavaScript environment.

- A JSON instance is a plain text string, formatted in a certain way according to the JSON standard rules. A JSON string is thus not limited to the JavaScript environment. It can exist in another programming language, or simply stored inside a plain text file or a database.

For example, we already saw that a JavaScript object can be created using an expression such as the following one -

var obj = {a: 1, b: 2};The corresponding JSON string can be defined and stored in a variable as follows -

var json = '{"a": 1, "b": 2}';Again, a JSON instance is a string, therefore enclosed in quotes. The JSON standard requires double quotes ("), so we need to enclose the entire string with single quotes (').

The other difference between how the above two variables are defined is that with JSON the property names are enclosed in quotes: "a" and "b" (we will immediately explain why).

To make JSON useful within the JavaScript environment, the JSON string can be parsed to produce an object. The parsing process - JSON→object - is done with the JSON.parse function -

JSON.parse(json); // Returns an objectThe JSON.parse function can thus be used to convert a JSON string (e.g. coming from a server) to a JavaScript object.

As we just saw, a JSON string should have quoted property names, as in '{"key":"value"}' and NOT '{key:"value"}'. The purpose of this convention is to avoid parsing errors in case when a key name is a reserved JavaScript keyword. For example, the following will result in an error -

JSON.parse('{while: 5}');Because while is a reserved keyword in JavaScript.

The following will work fine, since the word while is enclosed in quotes -

JSON.parse('{"while": 5}');The opposite conversion of object→JSON is done with JSON.stringify -

JSON.stringify(obj); // Returns a JSON stringThe JSON.stringify function is commonly used when sending an object from the JavaScript environment to a server. Since, like we said, JavaScript objects cannot exist outside of the JavaScript environment, we need to convert the object to a string with JSON.stringify before the data are sent elsewhere. For example, we use JSON.stringify in Chapter 13 when sending drawn layers to permanent storage in a database (Section 13.5).

Finally, keep in mind that JSON is limited in that it cannot store undefined values or functions. The only values that JSON can contain are all other data types -

- Strings

- Numbers

- Booleans

- Arrays

- Objects

null

For more details on the difference between a JavaScript object and a JSON string, check out the following StackOverflow question.

3.10.2 GeoJSON

GeoJSON is a spatial vector layer format based on JSON. Since GeoJSON is a special case of JSON, it can be easily processed in the JavaScript environment using the same methods as any other JSON string, such as using JSON.parse and JSON.stringify. For this reason, GeoJSON is the most common data format for exchanging spatial (vector) data on the web.

Here is an example of a GeoJSON string -

{

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [125.6, 10.1]

},

"properties": {

"name": "Dinagat Islands"

}

}This particular GeoJSON string represents a point layer with one attribute called name. The layer has just one feature, a point at coordinates [125.6, 10.1].

Don’t worry about the details of the GeoJSON format at this stage. We will cover how the GeoJSON format is structured in Chapter 7.

A variable containing the corresponding GeoJSON string can be created with the following expression -

var pnt = '{' +

'"type": "Feature",' +

'"geometry": {' +

'"type": "Point",' +

'"coordinates": [125.6, 10.1]' +

'},' +

'"properties": {' +

'"name": "Dinagat Islands"' +

'}' +

'}';Note that the string is defined piece by piece, concatenating with the + operator, for making the code more readable. We could likewise define pnt as a long string without needing +.

GeoJSON can be parsed with JSON.parse just like any other JSON -

pnt = JSON.parse(pnt); // Returns an objectNow that pnt is a JavaScript object, we can access its contents using the dot (or bracket) notation just like with any other object -

pnt.type; // Returns "Feature"

pnt.geometry.coordinates; // Returns [125.6, 10.1]

pnt.geometry.coordinates[0]; // Returns 125.6

pnt.properties; // Returns {name: "Dinagat Islands"}Going back to a GeoJSON string is done with JSON.stringify -

JSON.stringify(pnt); // Returns a stringGives the following result -

'{"type":"Feature","geometry":{"type":"Point", [...]'(Some of the characters are omitted and replaced with [...] to fit on the page)

Note that JSON.stringify takes further arguments to control the formatting of the object. For example, JSON.stringify(pnt, null, 4); will create the following indented, multi-line string much like the one we began with. This is much easier to read than the default one-line version shown above.

{

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [

125.6,

10.1

]

},

"properties": {

"name": "Dinagat Islands"

}

}3.11 Exercise

- Write a piece of JavaScript code, as follows

- The code starts with defining two arrays

- The first array represents a single coordinate

A, such as[100, 200]- The second array is an array of coordinate pairs

B, such as[[0, 3], [0, 4], [1, 5], [2, 5]]- The code then creates a new array, where the individual coordinate

Ais attached to each of the coordinates inB, so that we get an array of coordinate pairs -[[[100, 200], [0, 3]], [[100, 200], [0, 4]], [[100, 200], [1, 5]], [[100, 200], [2, 5]]].- Such an array can be useful for drawing line segments between a single points and a second set of points (Figure 11.8)

- Hint: Create an empty array

result, then run a loop that goes over the second arrayB, each time adding theAelement plus the currentBelement intoresult

References

Bassett, Lindsay. 2015. Introduction to Javascript Object Notation: A to-the-Point Guide to Json. “ O’Reilly Media, Inc.”