Chapter 4 JavaScript Interactivity

Last updated: 2018-11-11 20:44:58

4.1 The Document Object Model (DOM)

In Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 we mentioned that JavaScript is primarily used to control the interactive behavior of web pages. However, in our introduction to JavaScript in Chapter 3 we used the language in isolation: none of the code we executed in the console had any relation with the content of the web page where it was run. Indeed, how can we link our code with page content, to interactively modify it? This is precisely the subject of the current Chapter: employing JavaScript to query and modify page content. As we will see, the mechanism which makes the link possible is the Document Object Model (DOM).

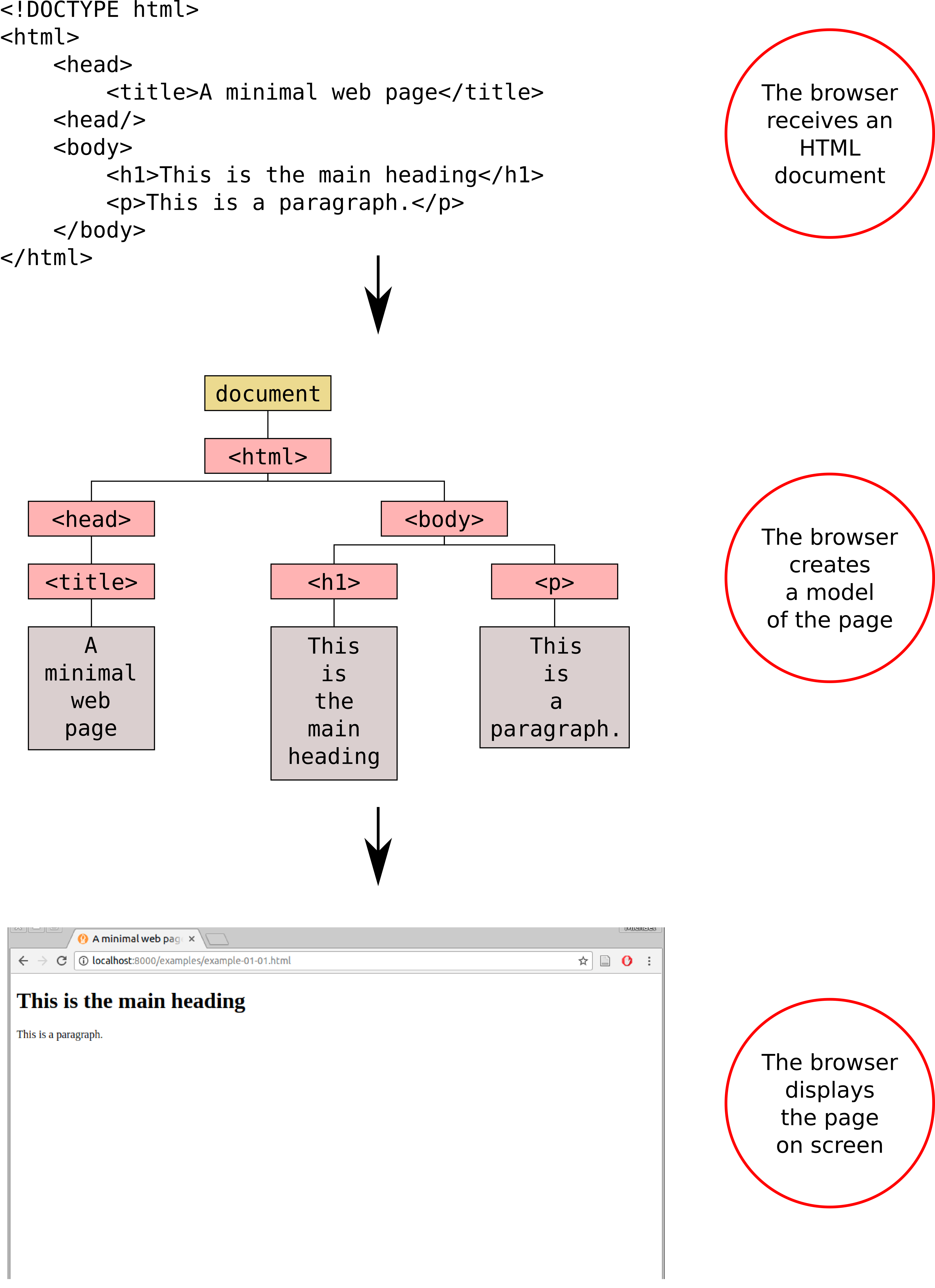

When a web browser loads an HTML file, it displays (renders) the contents of that file on the screen, possibly styled according to CSS rules. But that’s not all the web browser does with the tags, attributes, and text contents of the file. The browser also creates and memorizes a “model” of that page’s HTML. In other words, the web browser remembers the HTML tags, their attributes, and the order in which they appear in the file. This representation of the page is called the DOM.

FIGURE 4.1: The Document Object Model (DOM) is a representation of an HTML document, constructed by the browser on page load

The DOM is sometimes referred to as an Application Programming Interface (API) for accessing HTML documents with JavaScript. An API is a general term for methods of communication between software components. The DOM can be considered an API as it bridges between JavaScript code, and the displayed page content in the browser. The DOM basically provides the information and tools necessary to navigate through, make changes or additions, to the HTML on the page. The DOM itself isn’t actually JavaScript - it’s a standard from the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) that most browser manufacturers have adopted and added to their browsers.

4.2 Accessing and modifying elements

All of the properties, methods, and events of the DOM available for manipulating web pages are organized into objects, which are accessible through JavaScript code. Two of the most important objects are -

- The

windowobject, which represents the browser window - The

documentobject, which represents the document itself.

document is, in fact a property of window, i.e. document is a shortcut for window.document.

Using the properties and methods of the window and document objects, we are able to access document element content or their display settings, and also dynamically adjust them.

For example, the document object has a property named title, containing the text within the <title> element, or the page title. We can access this property, as a string, or modify it by assigning a new string.

- Browse to any web page in the browser

- Open the JavaScript console and try typing

document.titleandwindow.location.href- Check the type of returned values, using the

typeofoperator- Try assigning a new string into

document.title. The new title should appear on top of the browser window!- Go to any page (other then http://www.google.com) and type

window.location="http://www.google.com"into the console. What do you think has happened?

4.2.1 Accessing elements

The document.title property was just an example, referring to the specific <title> element. We need a more general method if we want to locate, and modify, specific elements in our document. The document object indeed contains several methods for finding elements in the DOM. These methods are called DOM selectors or DOM queries.

The following two expressions are examples of DOM selectors. Note that both are methods of the document object.

- The first selector uses the

.getElementByIdmethod to select an individual element with a specific ID,id="firstParagraph" - The second selector uses the

getElementsByClassNamemethod to select all elements with a specific class,class="important"

document.getElementById("firstParagraph");

document.getElementsByClassName("important");4.2.2 Modifying elements

The result of a DOM query is a reference to an element, or set of elements, in the DOM. That reference can be used to update the content or behavior of the element(s).

For example, the innerHTML property of a DOM element refers to the HTML code of that element. The following expression uses the innerHTML property to modify the HTML content of the element which has id="firstParagraph", replacing the current content with <b>Hello!</b>.

document

.getElementById("firstParagraph")

.innerHTML = "<b>Hello!</b>";Note that in this example the expression is split into three lines to fit on the page. However, remember that spaces and new-line symbols are ignored by the JavaScript interpreter. You can imagine the characters being merged back into a long single-line expression, then executed. In other words, the computer still sees a single expression here, where we assign a string into the .innerHTML property of an element selected using document.getElementById.

It is important to understand that the HTML source code and the DOM are two separate entities. While the HTML source code sent to the browser is constant, the DOM, which is initially constructed from the HTML source code, can be dynamically altered using JavaScript code. As long as no JavaScript code that modifies the DOM is being run, the DOM and the HTML source code are identical. However, when JavaScript code does modify the DOM, the DOM changes and the displayed content in the browser window changes accordingly.

The current DOM state can be examined, for example, using the Elements tab of the Developer tools (in Chrome). The HTML source code can be shown Ctrl+U (in Chrome), as we have already discussed in Section 1.2. Again, the source code remains exactly the same as initially sent from the server, no matter what happens on the page. This means that the HTML source code does not necessarily match the DOM once any JavaScript code was executed.

- While running the examples in this Chapter, you can compare these two locations to see how the DOM changes in response to executed JavaScript code, while the HTML source code maintains its initial version

4.2.3 Event Listeners

Sometimes we want to change the DOM at once, for example on page load. In many cases, however, we want to change the DOM dynamically, in response to user actions on the page, such as clicking on a button.

Each of the things that happens to a web page is called an event. Web browsers are programmed to recognize various events, including user actions such as -

- Mouse movement

- Pressing on the keyboard

- Resizing the browser window

An event represents the precise moment when something happens inside the browser. This is sometimes referred to the event being fired. There are different types of events, depending on the type of action taking place. For example, when you click a mouse, the precise moment you release the mouse button, the web browser signals that a "click" event has just occurred. In fact, web browsers fire several events whenever you click the mouse button. First, as soon as you press the mouse button, the "mousedown" event fires; then, when you let go of the button, the "mouseup" event fires; and finally, the "click" event fires.

To make your web page interactive, you need to write code that runs and does something useful in response to the appropriate type of event occurring on the appropriate element(s). This binded code is known as an event listener or event handler.

For example, we may wish to set an event listener which responds to user click on an interactive map by adding a marker in the clicked location (Section 11.2.2). In such case, we need to bind an event listener -

- to the map object,

- with a function for adding a marker

- which is executed in response to a mouse

"click"event

A mouse click is just one example, out of many event types the browser can detect. Table 4.1 specifies some commonly used ones.

| Type | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse | click |

Click |

"dblclick" |

Double click | |

"mousedown" |

Mouse button pressed | |

"mouseup" |

Mouse button released | |

"mouseover" |

Mouse cursor moves into element | |

"mouseout" |

Mouse cursor leaves element | |

"mousemove" |

Mouse moved | |

"drag" |

Element being dragged | |

| Keyboard | "input" |

Value changed in <input> or <textarea> |

"keydown" |

Key pressed | |

"keypress" |

Key pressed (character keys only) | |

"keyup" |

Key released | |

| Focus and Blur | "focus" |

Element gains focus (e.g. typing inside <input>) |

"blur" |

Element loses focus | |

| Forms | "submit" |

Form submitted |

"change" |

Form changed | |

| Document/Window | "load" |

Page finished loading |

"unload" |

Page unloading (new page requested) | |

"error" |

JavaScript error encountered | |

"resize" |

Browser window resized | |

"scroll" |

User scrolls on page |

In this book we will mostly use the "click", "mouseover", "mouseout" and "drag" events, all from the Mouse events category, as well as form "change" from the Forms category (Table 4.1). However, it is important to be aware of the other possibilities, such as events related to window resize or scrolling, or keyboard key presses.

4.2.4 Hello example

The next two examples demonstrate the idea of event listeners using plain JavaScript. We will not go into details in terms of syntax, because later on in this Chapter (Section 4.3), as well as throughout the book, we will learn an easier way of doing the same thing with the jQuery library.

Consider the following example -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello JavaScript</title>

</head>

<body>

<h2>JavaScript</h2>

<p id="demo">What can JavaScript do?</p>

<input type="button" value="Click Me!" id="change_text">

<script>

function hello() {

document

.getElementById("demo")

.innerHTML =

"JavaScript can change page contents!";

}

document

.getElementById("change_text")

.addEventListener("click", hello);

</script>

</body>

</html>In this example, we have a web page with an <h2> heading (without an ID), as well as two other elements with an ID -

- A

<p>element withid="demo" - An

<input>button element withid="change_text"

In the end of the <body>, we have a <script> element containing JavaScript code. We mentioned the <script> element in Section 1.5.3. Since the <script> element is in the end of the <body>, it will be executed by the browser after the HTML code is loaded and processed.

Let’s look at the last line in the JavaScript code -

document

.getElementById("change_text")

.addEventListener("click", hello);This above expression does several things -

- Selects the element which has

id="change_text"(the button), using thedocument.getElementByIdmethod - Attaches an event listener to it, using the

addEventListenermethod - The event listener specifies that when the element is clicked, the

hellofunction will be executed

What does the hello function do? According to its definition at the beginning of the <script>, we see that it has no parameters and just one expression -

function hello() {

document

.getElementById("demo")

.innerHTML =

"JavaScript can change page contents!";

}What this function does is -

- Selects the element with

id="demo"(the paragraph), again using thedocument.getElementByIdmethod - Replaces its HTML contents with

"JavaScript can change page contents!", by assignment into theinnerHTMLproperty

The complete code is given in example-04-01.html, and the result is shown on Figure 4.2.

FIGURE 4.2: example-04-01.html (Click to view this example on its own)

- Run the above example with the the Elements tab in Developer Tools open

- Click the

id="change_text"button and observe how the DOM is being modified- Note how the affected part of the DOM is momentarily highlighted each time the button is pressed

4.2.5 Poles example

The second example is slightly more complex, but the principle is the same -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Earth poles</title>

</head>

<body>

<h2>Earth Poles Viewer</h2>

<img id="myImage" src="images/north.svg"><br>

<input type="button" value="North Pole" id="north">

<input type="button" value="South Pole" id="south">

<script>

function showNorth() {

document

.getElementById("myImage")

.src = "images/north.svg";

}

function showSouth() {

document

.getElementById("myImage")

.src = "images/south.svg";

}

document

.getElementById("north")

.addEventListener("click", showNorth);

document

.getElementById("south")

.addEventListener("click", showSouth);

</script>

</body>

</html>In this example we add two event listeners, one for the North pole button and one for the South pole button. Both event listeners change the src attribute of the <img> element on the webpage. The North pole button sets src='images/north.svg', while the South pole button sets src='images/south.svg'. The resulting effect is that the displayed globe is switched from viewing the north pole or the south pole.

The result of example-04-02.html is shown on Figure 4.3.

FIGURE 4.3: example-04-02.html (Click to view this example on its own)

4.3 jQuery

So far we introduced the DOM, and saw how it can be used to (dynamically) modify page content. In the remainder of today’s Chapter, we will learn about the jQuery library which simplifies these (and other) types of common tasks.

A JavaScript library is a collection of pre-written JavaScript code which allows for easier development of JavaScript based applications. There are a lot of JavaScript libraries that simplify common tasks (e.g. DOM manipulation) or specialized tasks (e.g. web mapping), to make life easier for web developers. Often, you will be working with a library that is already written, instead of “reinventing the wheel” and writing your own JavaScript code for every single task.

jQuery is a JavaScript library that simplifies tasks related to interaction with the DOM, such as selecting elements and binding event listeners, such as what we did in the last two examples. Since this type of tasks is very common in JavaScript code, jQuery is currently the most widely deployed JavaScript library, by a large margin.

The main functionality of jQuery consists of -

- Finding elements using CSS-style selectors

- Doing something with these elements using jQuery methods

In the following Sections 4.4 through 4.9 we will introduce these two concepts while writing alternative implementations of the “Hello” and “Poles” examples from above (Sections 4.2.4 and 4.2.5, respectively). In the new versions, we will be using jQuery, instead of plain JavaScript, for selecting elements and binding event listeners.

In addition to its main functionality, jQuery has functions and methods to simplify other types of tasks in web development. For example, the $.each function, which we learn about in Section 4.11, simplifies the task of iterating over arrays and objects. Later on, in Section 7.6 we will learn about a technique for loading content into our web page called Ajax, which can also be simplified using jQuery.

4.4 Including the jQuery library

4.4.1 Including a library

Before using any object, function or method from jQuery, the library needs to be included on our web page. Practically, this means that the jQuery script is being run on page load, defining jQuery objects, functions and methods, which you can subsequently use in the other scripts on that page.

To include the jQuery library, or any other script for that matter, we need to place a <script> element referring to that script in our HTML document. Scripts for loading libraries are commonly placed inside the <head> of our document. Placing a <script> in the <head> means that the script is loaded before anything visible (i.e. the <body>) is loaded. This can be safer and easier for maintenance, yet with some performance implications. Namely, page load is being halted until the <scripts> elements have been processed. Since the jQuery script is very small (~90 kB), there is no noticeable delay for downloading and processing it, so we can safely place it in the <head>.

As mentioned in Section 1.5.3, when using the <script> element to load an external script file, we use the src attribute to specify file location. The location specified by src can be either a path to a local file, or a URL of a remote file hosted elsewhere on the web.

4.4.2 Loading a local script

When loading a script from a local file, we need to have an actual copy of the file on our server (more on that in Section 5.5). Basically, we need to download the jQuery code file, e.g. from the download section on the official jQuery website, and save it along with our HTML file. The first few lines of the document can then look as follows -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script src="jquery.js"></script>

<head/>

...4.4.3 Loading a remote script

When loading a remote file, hosted on the web in some other location other than our own computer, we need to provide a URL where the jQuery code file can be loaded from. A reliable option is to use a Content Delivery Network (CDN), such as the one provided by Google. A CDN is a series of servers designed to serve static files very quickly. In case we are loading the jQuery library from Google’s CDN, the first few lines of the document may appear as follows -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script src="https://ajax.[...]/jquery.min.js"></script>

<head/>

...The src attribute value is truncated with [...] to save space. Here is the complete URL that needs to go into the src attribute value -

https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/3.3.1/jquery.min.js

- Browse to the above URL to view the jQuery library contents. You can also download the file by clicking Save as… to view it in a text editor instead of a browser.

- You will note that the code is formatted in a weird way, with very few space and new line characters, which makes it hard for us to read.

- Can you guess what is the reason for this type of formatting?

Whether we refer to a local or remote file, the jQuery code will be loaded and processed by the browser, which means we can use its functions and methods in other scripts on that page.

4.5 Selecting elements

As mentioned above, the main functionality of jQuery involves selecting elements and then doing something with them.

With jQuery, we usually select elements using CSS-style selectors. To make a selection, we use the $ function defined in the jQuery library. The $ function can be invoked with a single parameter, the selector.

Most of the time, we can apply just the three basic CSS selector types (which we covered in Section 2.3) to get the selection we need. Using these selectors we target elements based on their element type, ID or class. For example -

$("a"); // Selects all <a> elements

$("#choices"); // Selects the element with id="choices"

$(".submenu"); // Selects all elements with class="submenu"The result of these expression is a jQuery object, which contains a reference to the selected DOM elements along with methods for doing something with the selection. For example, the jQuery object has methods for modifying the contents of all selected elements, or adding event listeners to them. These two types of methods will be discussed below in Sections 4.6 and 4.7, respectively.

It should be noted that jQuery also lets you use a wide variety of advanced CSS selectors to accurately pin-point the specific elements we need inside complex HTML documents. We will not be needing such selectors in this book. To get an impression of the various selector types in jQuery, check out the interactive demonstration by W3Schools, where the first few examples show basic selectors while the other examples show advanced ones.

4.6 Operating on selection

jQuery objects are associated with numerous methods for acting on the selected elements, from simply replacing HTML, to precisely positioning new HTML in relation to a selected element, to completely removing elements and content from the page. Table 4.2 lists some of the most useful jQuery methods for operating on selected elements, which we cover in the following sections.

| Type | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Getting/Changing content | .html() |

Get or set the content as HTML |

.text() |

Get or set content as text | |

| Adding content | .append() |

Add content before closing tag |

.prepand() |

Add content after opening tag | |

| Attributes and values | .attr() |

Get or set specified attribute value |

.val() |

Get or set value of input element |

There are many more jQuery methods that you can use. For other examples see the Working with Selections article by jQuery.

The following small webpage will be used to demonstrate the jQuery functionality discussed above: selecting elements and acting on selection.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>jQuery operating on selection</title>

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>

<head/>

<body>

<div id="page">

<h1 id="header">List</h1>

<h2>Buy groceries</h2>

<ul>

<li id="one" class="hot"><i>fresh</i> figs</li>

<li id="two" class="hot">pine nuts</li>

<li id="three" class="hot">honey</li>

<li id="four">balsamic vinegar</li>

</ul>

<h2>Comments</h2>

<input type="text" id="test3" value="Mickey Mouse">

</div>

</body>

</html>Figure 4.4 shows how this page appears in the browser.

FIGURE 4.4: example-04-03.html (Click to view this example on its own)

You can open the webpage and run the following expressions in the console to see their effect on page content.

4.6.1 .html()

The .html() method can both read the current HTML inside an element, and replace the current contents with some other HTML.

To retrieve the HTML currently inside the selection, just add .html() after the jQuery selection. For example, you can run the following command in the console where example-04-03.html is loaded -

$("#one").html();This should give the following output -

"<i>fresh</i> figs"In this example we were using a selector to select those elements with id="one", then we are using the .html() method on the selection which returns its HTML contents.

Note that if the selection contains more than one element, only the content of the first element is returned by the .html() method. For example, the following expression returns the same value as the previous one because the first <li> element on the page is also the one having id="one" -

$("li").html();If you supply a string as an argument to .html(), you replace the current HTML contents inside the selection. This can be seen as the jQuery alternative for assignment into the innerHTML property, which we saw in Section 4.2.2.

$("#one").html("<i><b>Not very</b> fresh</i> figs");In case the selection contains more than one element, the HTML contents of all elements is set to the new value. For example, the following expression will replace the contents of all list items on the page -

$("li").html("<i><b>Not very</b> fresh</i> figs");

- Open

example-04-03.htmland run the above expression in the console- Compare the HTML source code (Ctrl+U) and the DOM (Elements tab in the Developer tools)

- Which one reflects the above change, and why?

4.6.2 .text()

The .text() method works like .html(), but it does not accept HTML tags. It is therefore useful when you want to replace the text within a tag.

For example -

$("#two").text("pineapple");

- What do you think will happen if you pass text that contains HTML tags to the

.textmethod?- Try it in the console to check your answer

4.6.3 .append()

The .append() and .prepend() methods add new content inside the selected elements.

The .append() method adds HTML as the last child element of the selected element(s). For example, say you select a <div> tag, but instead of replacing the contents of the <div>, you just want to add some content before the closing </div> tag. The .append() method, when applied on the <div>, does just that.

The .append() method is also a great way to add an item to the end of a bulleted (<ul>) or numbered (<ol>) list. For example, the following expression adds a new list item at the end of our <ul> element -

$("ul").append("<li>ice cream</li>");4.6.4 .prepend()

The .prepend() method is like .append(), but adds HTML content as the first child of the selected element(s), that is, directly after the opening tag.

For example, we can use .prepend() to add a new item at the beginning, rather than the end, of our list -

$("ul").prepend("<li>bread</li>");4.6.5 .attr()

The .attr() method can get or set the the value of a specified attribute.

To get the value of an attribute of the first element in our selection, we specify the name of the attribute in the parentheses. For example, the following expression gets the class attribute value of the element which has id="one" -

$("#one").attr("class"); // Returns "hot"To modify the value of an attribute for all elements in our selection, we specify both the attribute name and the new value. For example, the following expression sets the class attribute of all <li> elements to "cold" -

$("li").attr("class", "cold");4.6.6 .val()

The .val() method gets or sets the current value of input elements such as <input> or <select> (see Section 1.5.12).

Note that .attr("value") is not the same as .val(). The former method gives the attribute value in the DOM, such as the initial value set in HTML code. The second gives the real-time value set by the user, such as currently entered text in a text box, which is not reflected in the DOM.

For example, the page we are experimenting with example-03-04.html contains the following <input> element -

<input type="text" id="test3" value="Mickey Mouse">The following expression gets the current value of that element, which is equal to "Mickey Mouse" unless the user interacted with the text area and typed something else.

$("#test3").val(); // Returns "Mickey Mouse"If you modify the contents of the text input area, and run the above expression again, you will see the new, currently entered text.

The following expression sets the input value to "Donald Duck", replacing the previous value of "Mickey Mouse" or whatever else that was typed into the text area -

$("#test3").val("Donald Duck");We will get back to another practical example using .val() and <input> elements later on in Section 4.13.

4.7 Adding event listeners

In addition to querying and modifying content, we can also add event listeners to the elements in our selection. At the beginning of this Chapter we added event listeners using plain JavaScript. In this section, we will do the same thing (in a simpler way) using jQuery.

jQuery objects contain the on method, which can be used to add event listeners to all elements in the respective selection. Similarly to the addEventListener method in plain JavaScript which we saw above (Section 4.2.4), the jQuery on method accepts two arguments -

- A specification of the event type(s) (Table 4.1) which are being listened to, such as

"click" - A function which is executed each time the event fires

For example, to bind a "click" event listener to all paragraphs on a page, you can do this -

$("p").on("click", myFunction);Where myFunction is a function which defines what should happen each time the user clicks on a <p> element.

The function we pass to the event listener does not need to be a predefined, named one. You can also use an anonymous function definition (see Section 3.7). For example, here is another version of the above event listener definition, this time using an anonymous function -

$("p").on("click", function() {

// code goes here

});We can also add multiple event listeners to the same element selection, in order to trigger different responses for different events.

In the following example-04-04.html two event listeners are attached to the id="p1" paragraph. The first event listener responds to the "mouseover" event (i.e. mouse cursor entering the element), printing "You entered p1" in the console. The second event listener responds to the "mouseout" event (i.e. mouse cursor leaving the element), printing "You left p1" in the console.

$("#p1")

.on("mouseover", function() {

console.log("You entered p1!");

})

.on("mouseout", function() {

console.log("You left p1!");

});As a result, the phrases the "You entered p1!" or "You left p1!" are interchangeably printed in the console whenever the user moves the mouse into the paragraph or out of the paragraph.

At this stage you may note our code starts to have a lot of nested brackets of both types, ( and {. This is typical of JavaScript code, and a common source of errors while learning the language. Make sure you keep track of opening and closing brackets. Advanced text editors, such as Sublime, automatically highlight opening/closing bracket pairs, which may help with structuring the code and avoiding mistakes.

The small web page implementing the above pair of event listeners (example-04-04.html) is shown on Figure 4.5.

FIGURE 4.5: example-04-04.html (Click to view this example on its own)

- Open the above example in the browser and open the console

- Move the mouse cursor over the

#p1paragraph and check out the messages being printed in the console- Try modifying the source code of this example so that the messages are displayed on the web page itself, instead of the console. Hint: create another paragraph for containing the messages, and use the

.textmethod

4.8 Hello example

We have now covered everything we need to know to translate the “Hello” and “Light Bulb” examples to jQuery syntax.

We will start with the “Hello” example where clicking on a button modifies the HTML content of a <p> element (Section 4.2.4).

First of all, we need to include the jQuery library. We add the jQuery library from a CDN with the following line of code inside the <head> element. We are using a local file named jquery.js, which is stored in a directory named js placed along with our index.html file, which is why the file path is specified as js/jquery.js. We will elaborate on file structures and file paths for loading content in websites in Section 5.5.

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>Next we can replace the following <script> contents -

function hello() {

document

.getElementById("demo")

.innerHTML =

"JavaScript can change page contents!";

}With the equivalent jQuery version -

function hello() {

$("#demo").html("JavaScript can change page contents!");

}

$("#change_text").on("click", hello);In the last expression, the #change_text element is selected to add a click event listener to it. Whenever the user clicks on the button, the hello function is executed. The contents of the hello functions also uses a selector, this time accessing the #demo element. Once selected, the .html function changes the HTML content of the element to the "Hello JavaScript!" text.

Note that for a shorter, though perhaps less manageable code, we could use an anonymous function inside the event listener definition -

$("#change_text").on("click", function() {

$("#demo").html("JavaScript can change page contents!");

});Here is the complete code of the modified “Hello” version given in example-04-05.html -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello JavaScript (jQuery)</title>

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<h2>JavaScript</h2>

<p id="demo">What can JavaScript do?</p>

<input type="button" value="Click Me!" id="change_text">

<script>

function hello() {

$("#demo")

.html("JavaScript can change page contents!");

}

$("#change_text").on("click", hello);

</script>

</body>

</html>Figure 4.6 shows that the new version is visually (and functionally) the same; only the underlying code is different, using jQuery rather than plain JavaScript.

FIGURE 4.6: example-04-05.html (Click to view this example on its own)

4.9 Poles example

Let’s modify the Poles example to use jQuery too. Again, we need to include the jQuery library in the <head> element. Then, we replace the original <script> which we saw in Section 4.2.5-

function showNorth() {

document

.getElementById("myImage")

.src = "images/north.svg";

}

function showSouth() {

document

.getElementById("myImage")

.src = "images/south.svg";

}

document

.getElementById("north")

.addEventListener("click", showNorth);

document

.getElementById("south")

.addEventListener("click", showSouth);Into the following alternative version -

function showNorth() {

$("#myImage")

.attr("src", "images/north.svg");

}

function showSouth() {

$("#myImage")

.attr("src", "images/south.svg");

}

$("#north").on("click", showNorth);

$("#south").on("click", showSouth);The concept is similar to the previous example, only that instead of changing the HTML content of an element with html(), we are changing the src attribute with attr().

Here is the complete code of the modified “Poles” version given in example-04-06.html -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<h2>Earth Poles Viewer</h2>

<img id="myImage" src="images/north.svg"><br>

<input type="button" value="North Pole" id="north">

<input type="button" value="South Pole" id="south">

<script>

function showNorth() {

$("#myImage")

.attr("src", "images/north.svg");

}

function showSouth() {

$("#myImage")

.attr("src", "images/south.svg");

}

$("#north").on("click", showNorth);

$("#south").on("click", showSouth);

</script>

</body>

</html>The result is shown on Figure 4.7.

FIGURE 4.7: example-04-06.html (Click to view this example on its own)

4.10 The event object

So far the functions which we used inside an event listener did not use any information regarding the event itself, other than the fact the event has happened. Sometimes, however, we may be interested in functions which can have a variable effect, depending on event properties: such as where and when the event happened.

In fact, every time an event happens, an event object is passed to any event listener function responding to the event. We can use this object to construct functions which have variable effects depending on event properties.

The event object has methods and properties related to the event that occurred. For example -

.type- Type of event ("click","mouseover", etc.).key- Button or key was pressed.pageX,.pageY- Mouse position.timeStamp- Time, as number of milliseconds from Jan 1st, 1970

A list of all standard event object properties can be found in the HTML DOM Events reference by W3Schools.

Every function that responds to an event can take the event object as its parameter. That way, we can use the event object properties in the function body, to trigger a specific action according to the properties of the event.

The following small page example-04-07.html uses the .pageX and .pageY properties of the "mousemove" event to display up-to-date mouse coordinates every time the mouse moves on screen.

Note how the event object (conventionally named e, but you can choose another name) is now a parameter of the event listener function. Also note that we are using the $(document) selector, since we want to “listen to” mouse movement over the entire document.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<p id="position"></p>

<script>

$(document).on("mousemove", function(e) {

$("#position").text(e.pageX + " " + e.pageY);

});

</script>

</body>

</html>The result is shown on Figure 4.8.

FIGURE 4.8: example-04-07.html (Click to view this example on its own)

Keep in mind that different types of events are associated with different event object properties, and that custom event types and event properties can be defined in different JavaScript libraries.

For example, later on in the book we will use the map click event to detect the clicked coordinates on an interactive map, then to trigger specific actions regarding that location. This is made possible by the fact that the "click" event on a map contains a custom property named .latlng, which can be read by the event listener function. We will see how this technique can be used for several purposes, such as -

- Displaying the clicked coordinates (Section 6.9)

- Adding a marker in the clicked location on the map (Section 11.2)

- Querying data based on proximity from the clicked location (Section 11.4)

In Chapter 13 we will see another group of custom events referring to drawing and editing shapes on the map, such as draw:created which is fired when a new shape is drawn on the map.

4.11 Iteration over objects

As mentioned earlier, the jQuery library has several functions for tasks other than selecting elements and operating on selection. One such function is $.each. The $.each function is a general function for iterating over JavaScript arrays and objects. This function can be used as a cleaner and shorter alternative to for loops (Section 3.9.2), in cases when we need to do something on each element of an array or an object.

The $.each function accepts two arguments -

- The array or object

- A function that will be applied on each element

The second argument, that is the function passed to $.each, can also take two arguments -

key- The index (for an array) or the property name (for an object)value- The contents of the element (for an array) or the property value (for an object)

Note that, like with e for “event”, the parameter names key and value are chosen by convention. We could choose any pair of different names. The important point is that the first parameter refers to the index or property name, and the second parameter refers to the contents or the property value.

For example, check out the following code -

var a = [52, 97, 104, 20];

$.each(a, function(key, value) {

console.log("Index #" + key + ": " + value);

});In the first expression, an array named a is defined. In the second expression, we are applying an (anonymous) function on each item of a. The function takes two arguments, key and value, and constructs a text string which is printed in the console for each item. Note that the .each() method returns the array itself, which is why it is also being printed in the console.

- Open a web page where the jQuery library is loaded, such as

example-04-07.html- Run the above code and examine the printed output

4.12 Modifying page based on data

One of the most important use cases of JavaScript is dynamically generating page content based on data. The data we wish to display on the page can come from various sources, such as an object in the JavaScript environment, a file, or a database. JavaScript code can be used to process the data into HTML elements, which can then be added to the DOM (as shown in Section 4.6 above) and consequently displayed in the browser. Modifying page contents based on data is also a use case where iteration (Section 4.11) turns out to be very useful.

For our next example, let’s assume we need to dynamically create a list of items on our page, and we have an array with the content that should go into each list item. We will use the jQuery $.each() function for iterating over an array and adding its contents into an <ul> element on the page.

For example, suppose we have the following array named data, including the Latin names of eight Oncoyclus Iris species found in Israel -

var data = [

"Iris atrofusca",

"Iris atropurpurea",

"Iris bismarckiana",

"Iris haynei",

"Iris hermona",

"Iris lortetii",

"Iris mariae",

"Iris petrana"

];In the DOM, we may initially have an empty <ul> placeholder -

<ul id="species"></ul>Which we would like to fill with the following HTML content based on the array, using JavaScript -

<ul id="species">

<li><i>Iris atrofusca</i></li>

<li><i>Iris atropurpurea</i></li>

<li><i>Iris bismarckiana</i></li>

<li><i>Iris haynei</i></li>

<li><i>Iris hermona</i></li>

<li><i>Iris lortetii</i></li>

<li><i>Iris mariae</i></li>

<li><i>Iris petrana</i></li>

</ul>(Note that each species name is shown in italics)

Why not embed the above HTML code directly into the HTML document then, instead of constructing it with JavaScript? Two reasons why the former may not always be a good idea -

- The content can be much longer, e.g. tens or hundreds of elements, which means it is less convenient to type the HTML by hand. Though we can use various tools, such as Pandoc, to programmatically convert text plus markup to HTML, thus reducing the need to manually type all of the HTML tags, but then it is probably more flexible to do the same with JavaScript anyway

- We may want to build page content based on real-time data, loaded each time the user accesses the website, and/or make it responsive to user input. For example, a list of headlines in a news website can be based on a real-time news stories database and/or customized to user preferences

To build the above HTML code automatically, based on the data array, we can use the $.each() method we just learned. First, recall that $.each accepts a function that can do something with the key and value of each array element, such as printing them into the console -

$.each(data, function(key, value) {

console.log([key, value]);

});Check out the printed output (below). It includes eight arrays. In each array, the first element is the key (the index: 0, 1, …) and the value (the species name string).

[0, "Iris atrofusca"]

[1, "Iris atropurpurea"]

[2, "Iris bismarckiana"]

[3, "Iris haynei"]

[4, "Iris hermona"]

[5, "Iris lortetii"]

[6, "Iris mariae"]

[7, "Iris petrana"]

- Replace the

dataarray with thedirectoryobject from Section 3.9.2- Run the above code to print the

keyandvalueof each item indirectory- How did the

keyandvaluechange?- Repeat the exercise with

directory.musicians. What happened now?

Now that we know how to iterate over our array data, we just need to modify the function that is being applied so that instead of printing the array contents in the console it will add a new <li> with the species name.

To do that, we can -

- Create the empty

<ul>placeholder element in our document (using HTML), as shown above - Iterate over the

dataarray, each time adding a<li>element as the last child of the<ul>(using JavaScript)

To create an empty <ul> element, we can add the following inside the <body> of the HTML document -

<p>List of rare <i>Iris</i> species in Israel:</p>

<ul id="species"></ul>Note that we are using an ID to identify the particular <ul> element, in this case id="species". This is very important since we need to identify the particular element which our JavaScript code will operate on!

Next, to add a new <li> element inside the <ul> element, we can use the append() method, which inserts specified content at the end of the selected element(s).

For example, the following expression will add a <li> element at the end of the <ul> element (which is initially empty) -

$("#species")

.append("<li><i>A list item added with jQuery<i></li>");

- Open

example-04-08.htmlin the browser- Run the above expression several times, to see more and more items being added to the list

Replacing the constant <li> with a dynamic one, based on current value, and encompassing it inside the $.each iteration, the final expression looks like this -

$.each(data, function(key, value) {

$("#species").append("<li><i>" + value + "</i></li>");

});The above means we are iterating over the data array, each time adding a new <li> at the bottom of our list, with the content being the current element value (in italics).

Here a small web page example-04-08.html implementing all of the above -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Populating list</title>

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<p>List of rare <i>Iris</i> species in Israel:</p>

<ul id="species"></ul>

<p>It was created dynamically using jQuery.</p>

<script>

var data = [

"Iris atrofusca",

"Iris atropurpurea",

"Iris bismarckiana",

"Iris haynei",

"Iris hermona",

"Iris lortetii",

"Iris mariae",

"Iris petrana"

];

$.each(data, function(key, value) {

$("#species")

.append("<li><i>" + value + "</i></li>");

});

</script>

</body>

</html>The result is shown on Figure 4.9.

FIGURE 4.9: example-04-08.html (Click to view this example on its own)

Again, in this small example the advantage of generating the list with JavaScript, rather than writing the HTML code by hand, may not be evident. However, this technique is very powerful in more realistic settings, such as when our data is much larger and/or needs to be constantly updated. For example, in Section 10.4.4 we will use this technique to dynamically generate a dropdown list with dozens of plant species names according to real-time data coming from a database.

4.13 Working with user input

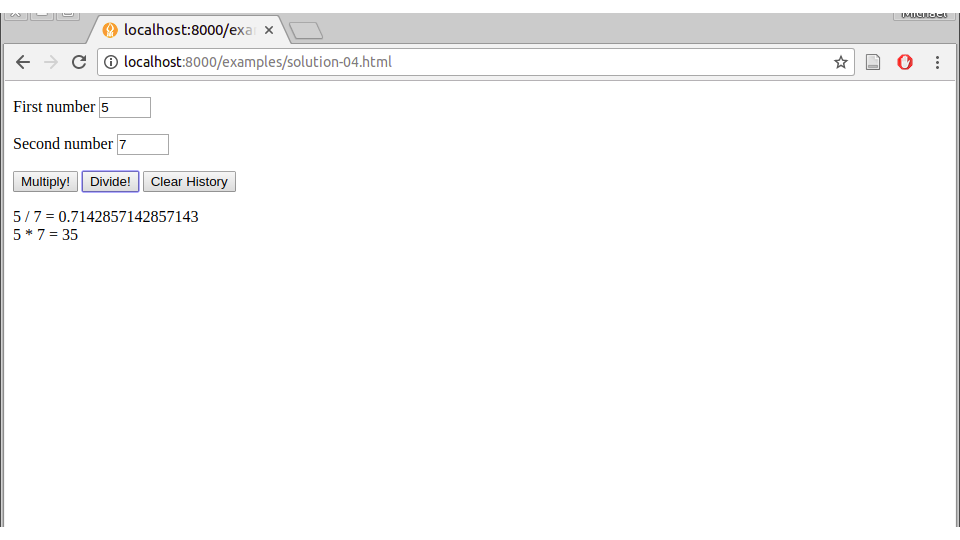

Our last topic in this Chapter concerns dynamic responses to user input on the page. As an example, we will build a simple calculator app where clicking on a button multiplies two numbers the user entered, and prints the result on screen (Figure 4.10).

In fact, we already covered everything we need to know to write the code for such an application. The only thing different from the previous examples is that we are going to use the .val() method (Section 4.6.6 above) to query the currently entered user input.

As usual, we start with HTML code. Importantly, the code contains three <input> elements -

- The first number (

type="number") - The second number (

type="number") - The Multiply! button (

type="button")

Here is the code of just those <input> elements -

<input type="number" id="num1" min="0" max="100" value="5">

<input type="number" id="num2" min="0" max="100" value="5">

<input type="button" id="multiply" value="Multiply!">Note that all input elements are associated with IDs: num1, num2 and multiply. We need those for referring to the particular elements in our JavaScript code.

Below the <input> elements, we will have an empty <p> element. This element will hold the multiplication result. Initially, the paragraph is empty, but it will be filled with content using JavaScript code.

<p id="result"></p>The only scenario where the contents of the page changes is when the user clicks on the Multiply! button. Therefore, our <script> is in fact composed of just one event listener, responding to "click" events on the Multiply! button -

$("#multiply").on("click", function() {...});The function being passed to the event listener modifies the text content of the <p> element. The new text content contains the multiplication result, using the .val() method to extract both input numbers $("#num1").val() and $("#num2").val() -

$("#multiply").on("click", function() {

$("#result")

.text(

"The result is: " +

$("#num1").val() * $("#num2").val()

);

});It is important to note that all input values are returned as text strings, even in numeric <input> elements. You can see this by opening example-04-09.html and typing $("#num1").val() in the console. However, when using the multiplication operator * strings are automatically converted to numbers, which is why multiplication still works.

Here is the complete code for our multiplication web page example-04-09.html -

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Working with user input</title>

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<p>First number

<input type="number" id="num1" min="0" max="100" value="5">

</p>

<p>Second number

<input type="number" id="num2" min="0" max="100" value="5">

</p>

<input type="button" id="multiply" value="Multiply!">

<p id="result"></p>

<script>

$("#multiply").on("click", function() {

$("#result")

.text(

"The result is: " +

$("#num1").val() * $("#num2").val()

);

});

</script>

</body>

</html>The result is shown on Figure 4.10.

FIGURE 4.10: example-04-09.html (Click to view this example on its own)

4.14 Exercise

- Modify

example-04-09.htmlby adding the following functionality- Make calculator history append at the top (Figure 4.11), to keep track of the previous calculations. For example, if the user multiplied 5 by 5, then 5*5=25 will be added on top of all other history items. If the user made another calculation, it will be added above that, and so on.

- Add a second button for making division of the two input numbers.

- Add a third button for clearing all previous history from screen. Hint: you can use

.html("")to clear the results.

FIGURE 4.11: solution-04.html