Chapter 10 Combining rasters and vector layers

Last updated: 2020-08-12 00:39:38

Aims

Our aims in this chapter are:

- Crop and mask a raster according to a vector layer

- Switch from vector to raster representation, and vice versa

- Extract raster values from locations defined by a vector layer

We will use the following R packages:

sfstarsunits

10.1 Masking and cropping rasters

10.1.1 Introduction

Masking a raster means turning pixels values outside of a an area of interest—defined using a polygonal layer—into NA (Figure 10.1). Cropping a raster means deleting whole rows and/or columns, so that raster extent is reduced to a new (smaller) rectangular shape, also according to the extent of a vector layer. The [ operator can be used for masking or masking and cropping (the default).

Figure 10.1: Masking a raster48

10.1.2 Masking and cropping

For an example of masking and cropping, we will prepare a raster of average NDVI over the period 2000-2019, based on MOD13A3_2000_2019.tif. The following code section combines what we learned in Sections 6.3.2, 6.6.1.3 and 9.3:

library(stars)

r = read_stars("MOD13A3_2000_2019.tif")

names(r) = "NDVI"

r = st_warp(r, crs = 32636)

r_avg = st_apply(r, 1:2, mean, na.rm = TRUE)

names(r_avg) = "NDVI"

dates = read.csv("MOD13A3_2000_2019_dates2.csv", stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

dates$date = as.Date(dates$date)

r = st_set_dimensions(r, 3, values = dates$date, names = "time")We will also read a Shapefile with a polygon of Israel borders, named israel_borders.shp:

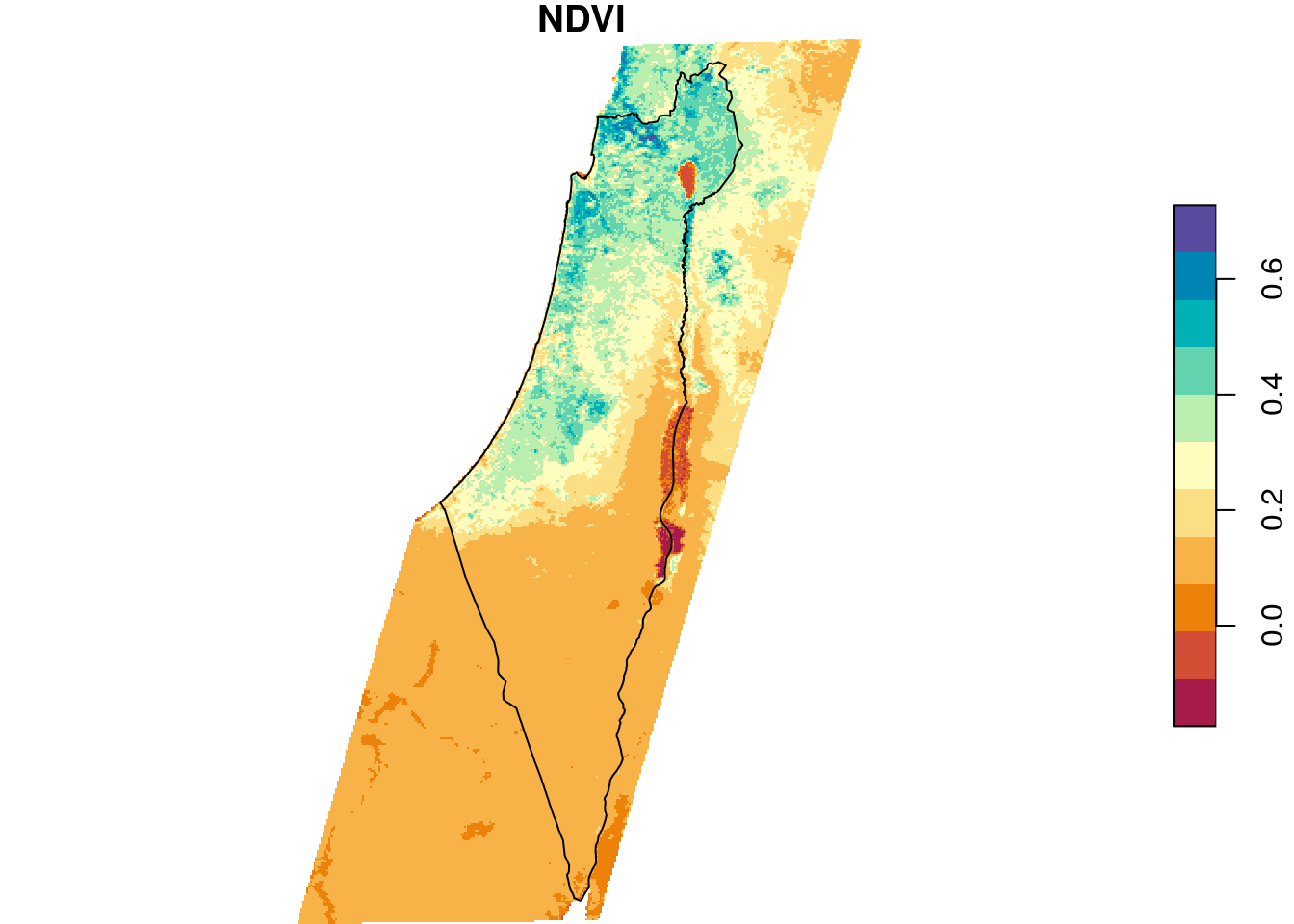

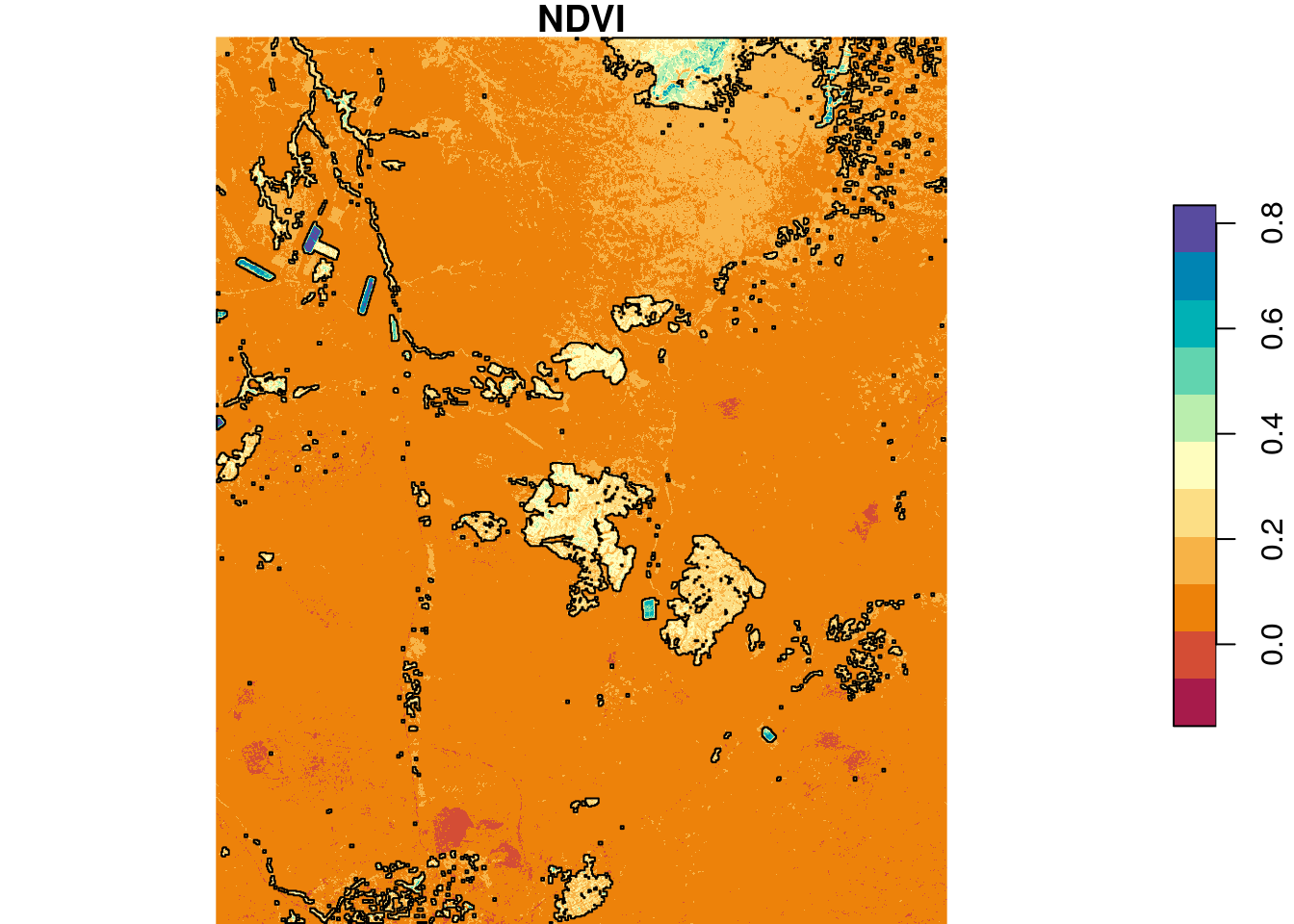

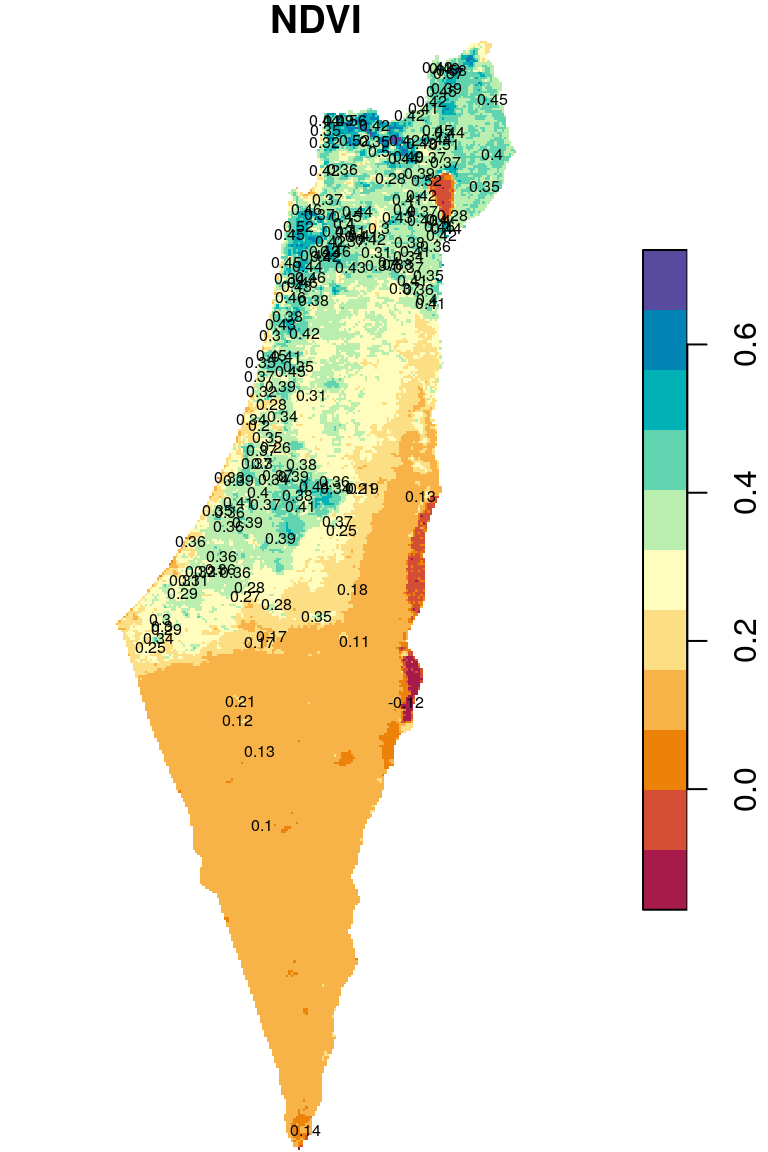

Figure 10.2 shows the average NDVI raster and the borders polygon:

plot(r_avg, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(11, "Spectral"), reset = FALSE)

plot(st_geometry(borders), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.2: Raster and crop/mask geometry

Masking and cropping a raster based on an sf layer can be done with the [ operator, as follows:

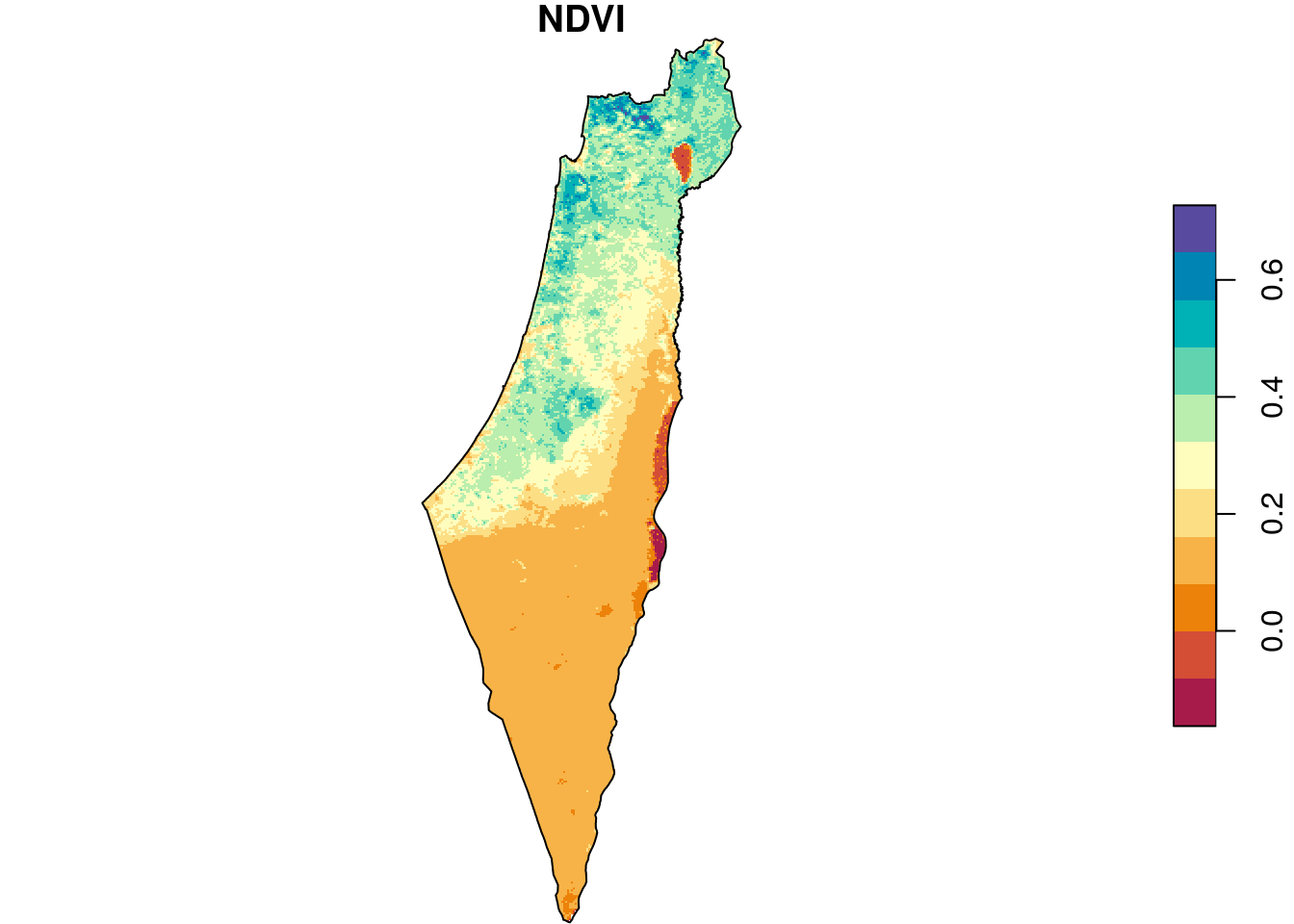

As we can see in Figure 10.3, all pixels that were outside of the polygon are now NA (this is called masking). It’s difficult to see, but the raster extent is also slightly reduced according to the extent of borders (this is called cropping):

plot(r_avg, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(11, "Spectral"), reset = FALSE)

plot(st_geometry(borders), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.3: Raster after cropping and masking

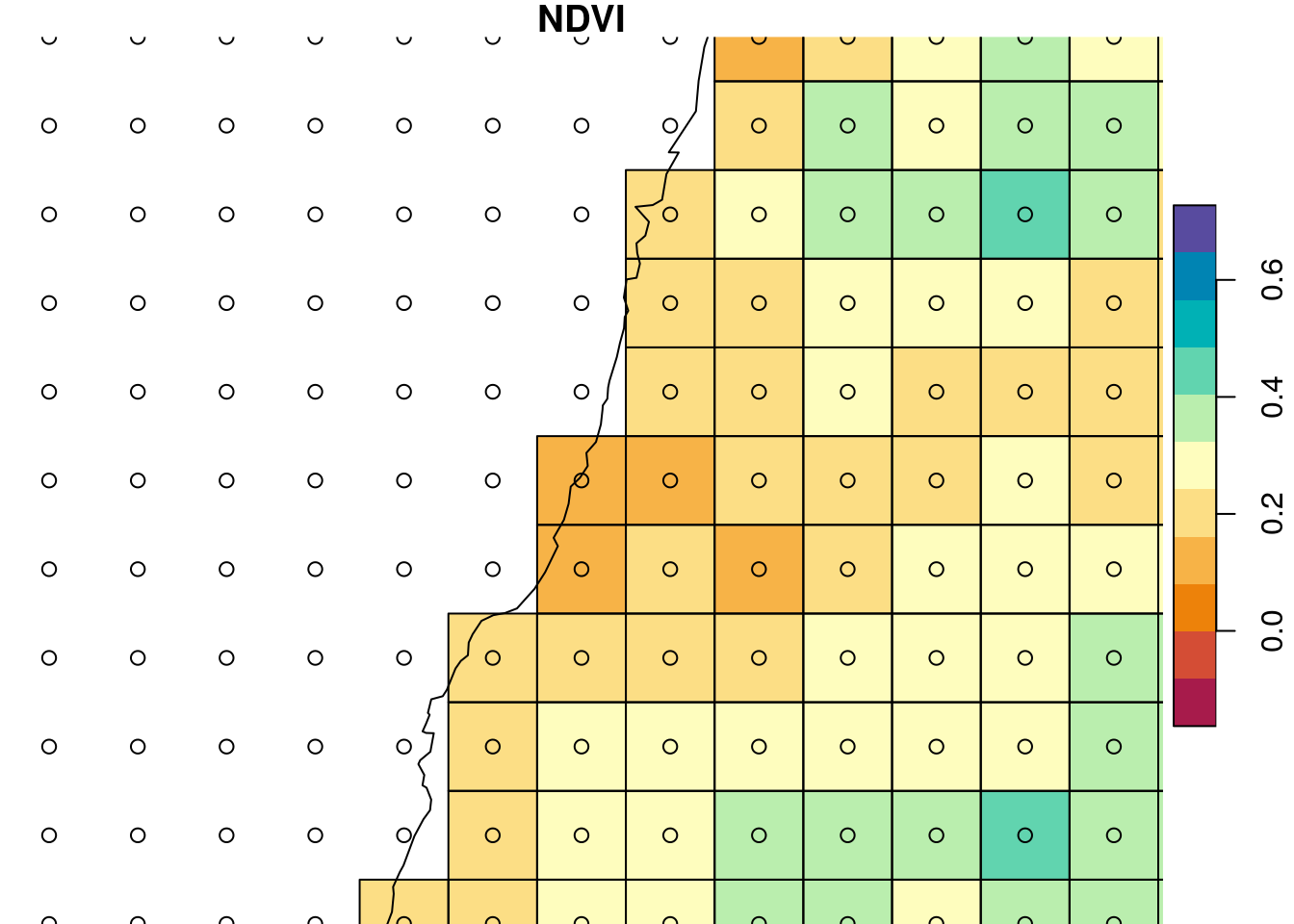

Zooming in on a small portion of the masked raster (Figure 10.4) demonstrates that pixels whose center is not inside polygon were converted to NA:

x = r_avg[, 50:60, 150:160]

plot(

r_avg, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(11, "Spectral"), reset = FALSE,

xlim = range(st_coordinates(x)[,1]), ylim = range(st_coordinates(x)[,2])

)

plot(st_as_sfc(r_avg, as_points = TRUE), add = TRUE)

plot(st_geometry(borders), add = TRUE)

plot(st_geometry(st_as_sf(r_avg)), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.4: Raster after cropping and masking

10.1.3 Masking-only

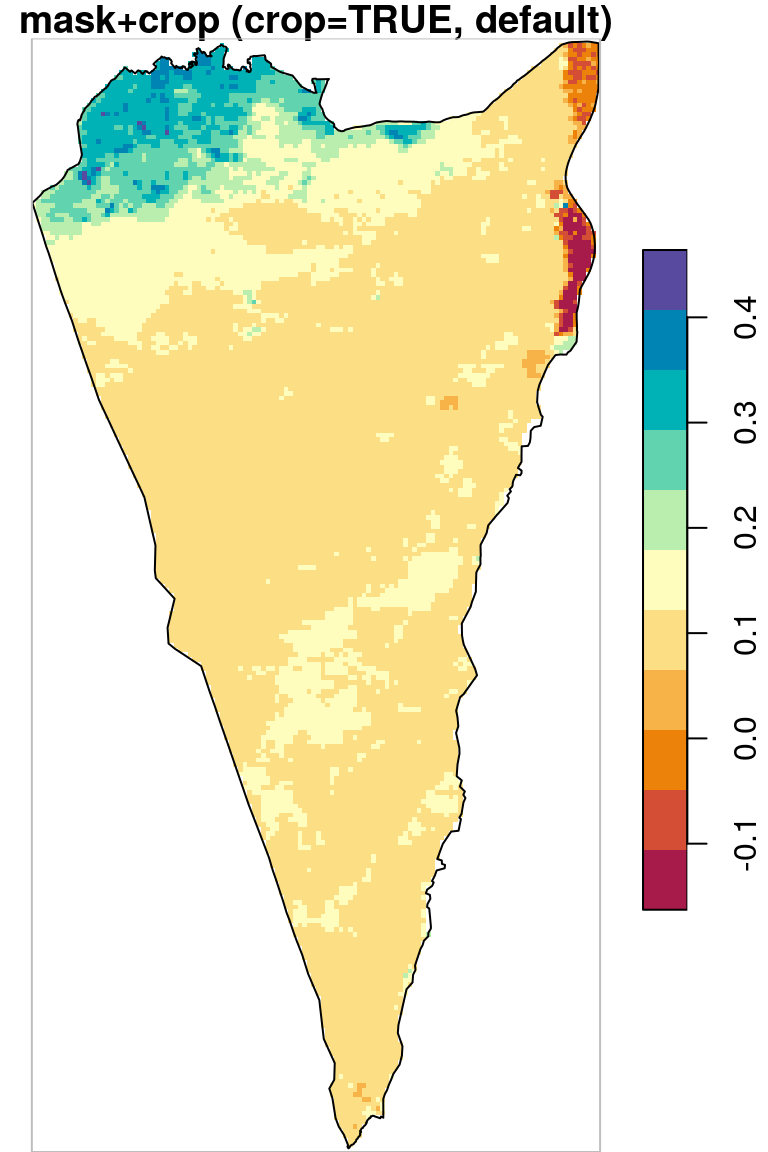

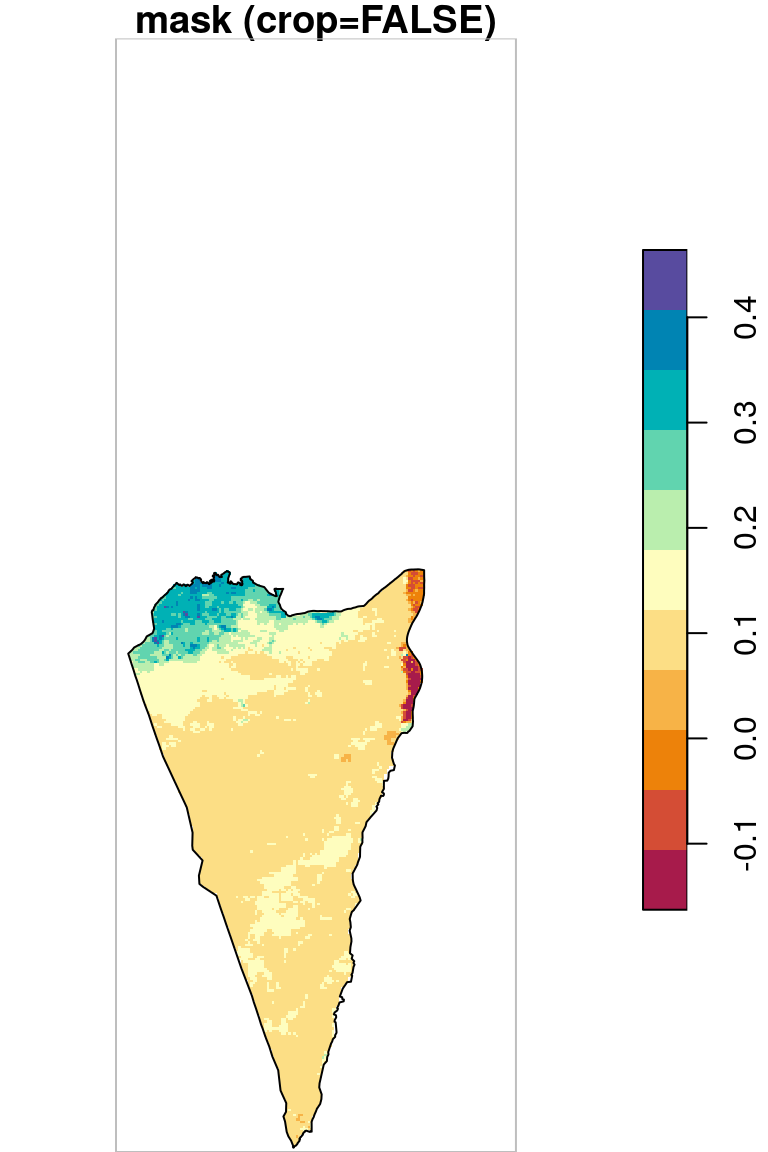

Masking-only is done with the same operator ([), using the (non-default) argument crop=FALSE. To demonstrate the difference between masking+cropping (which we just did) and masking only, consider the following example where r_avg is masked and cropped (r_avg1), or just masked (r_avg2), according to the "Negev" administrative area. First we prepare the polygon used for masking and cropping, obtained from a Shapefile named nafot.shp:

nafot = st_read("nafot.shp", stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

nafot = st_transform(nafot, st_crs(r))

pol = nafot[nafot$name_eng == "Be'er Sheva", ]Then we produce the masked+cropped (r_avg1) and masked (r_avg2) rasters:

As we can see in Figure 10.5, masking transforms pixel values to NA (left panel) while cropping reduces raster extent by deleting whole rows and columns (right panel).

plot(r_avg1, key.pos = 4, reset = FALSE, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(11, "Spectral"), main = "mask+crop (crop=TRUE, default)")

plot(st_geometry(pol), add = TRUE)

plot(st_as_sfc(st_bbox(r_avg1)), border = "grey", add = TRUE)

plot(r_avg2, key.pos = 4, reset = FALSE, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(11, "Spectral"), main = "mask (crop=FALSE)")

plot(st_geometry(pol), add = TRUE)

plot(st_as_sfc(st_bbox(r_avg2)), border = "grey", add = TRUE)

Figure 10.5: Cropping and masking (left) vs. masking (right), raster extent is shown in grey

Note that for plotting the raster extents (grey boxes in Figure 10.5), the above code section uses a combination of st_bbox and st_as_sfc. The combination returns the bounding box of a stars (or sf) layer as an sfc (geometry) object. For example, the following expression returns a geometry column with a single polygon, which is the bounding box of r_avg1:

10.2 Vector layer → raster

10.2.1 Introduction

The st_rasterize function converts a vector layer to a raster, given two arguments:

sf—The vector layer to converttemplate—A raster “template” (if missing it can be generated automatically)

The resulting raster retains the original values (from the template) in pixels that do not overlap with the vector layer (Figure 10.6). In those pixels that do overlap with the vector layer, the value of the (first) vector layer attribute is “burned” into those pixels. The values are burned sequentially, according to the order of features. Therefore, when there are more than one vector features coinciding with the same pixel, the last feature “wins”.

Figure 10.6: Conversion of points, lines and polygons to raster49

10.2.2 Rasterizing polygon attributes

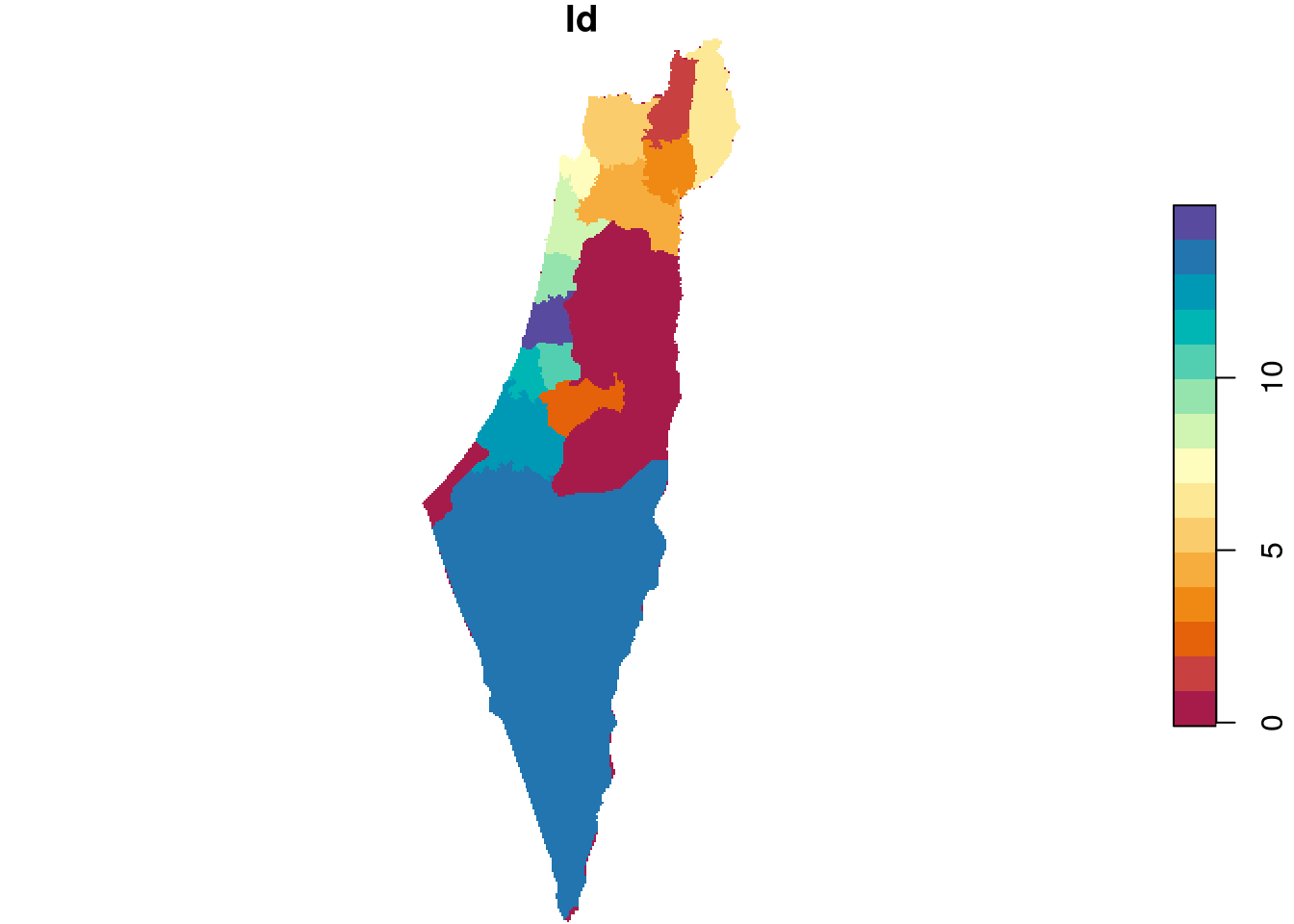

For example, let’s rasterize the nafot vector layer to a raster, using r_avg as a template. The attribute which will be burned into the raster is the Id of the administrative area:

The resulting raster s has the same dimensions of r_avg but different values, as shown on Figure 10.7. We can see that those areas not covered by the nafot layer retained their original value (average NDVI). All pixels that were covered by nafot got the attribute value (Id).

Figure 10.7: Rasterizing the Id of the nafot administrative areas layer into the average NDVI raster

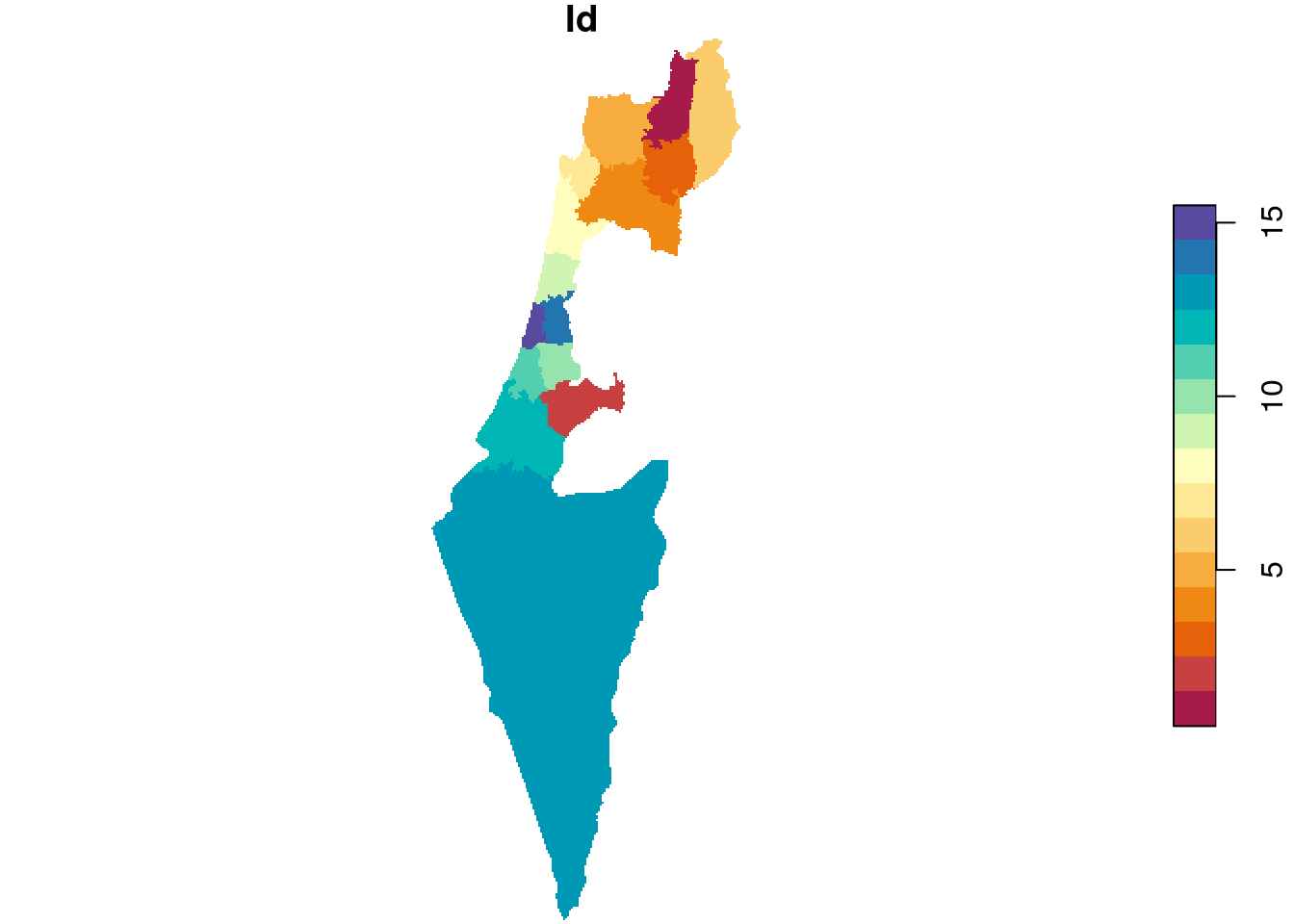

Often we want to start with an empty template, so that the only values in the resulting raster are those “burned” from the vector layer. For example, we can use a copy of the r_avg raster, where all of the pixel values are replaced with NA, as the template:

The result is shown in Figure 10.8:

Figure 10.8: Rasterizing into an empty template

10.2.3 Rasterizing point counts

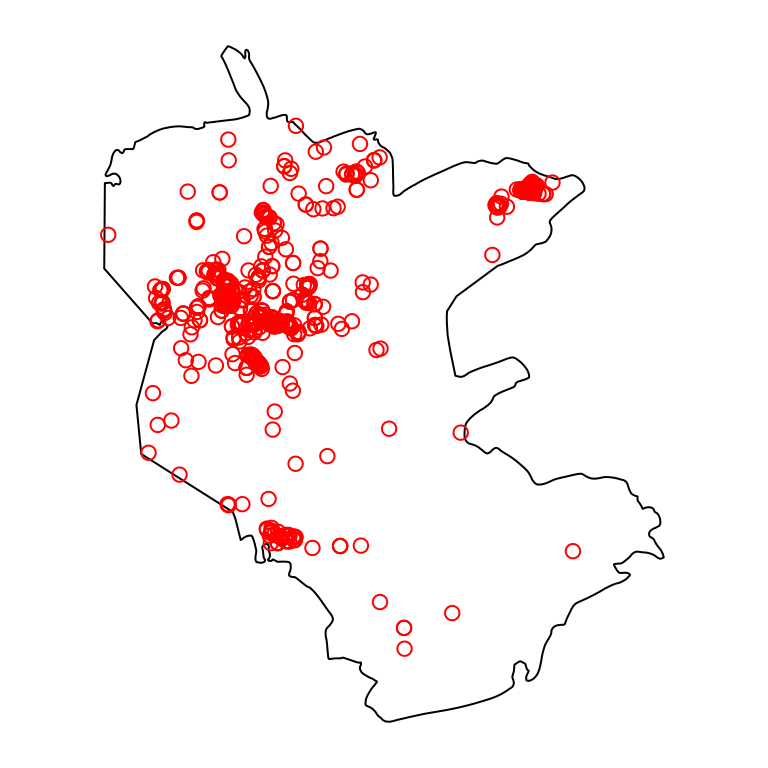

Sometimes we want to add up attribute values from overlapping features coinciding with the same pixel, rather that take the last value. This is useful, for instance, when calculating a point density raster. For example, let’s read the plants.shp and reserve.shp Shapefiles, containing a point layer of rare plants observations and a polygon with the borders of a nature reserve in the Negev:

plants = st_read("plants.shp", stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

reserve = st_read("reserve.shp", stringsAsFactors = FALSE)We will also reproject both layers to UTM, and subset only those plants that are inside the reserve:

plants = st_transform(plants, 32636)

reserve = st_transform(reserve, 32636)

plants = plants[reserve, ]Figure 10.9 shows both layers—the polygonal layer reserve and the point layer plants:

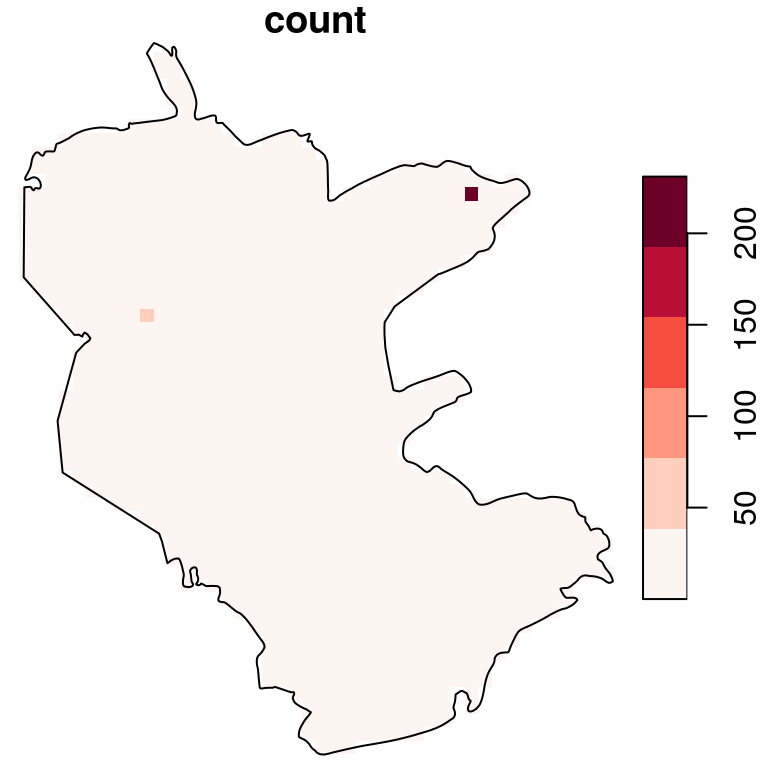

Figure 10.9: Nature reserve and rare plants observations

How can we calculate a raster expressing the density of plants points across the nature reserve? First, we set up a empty template raster, but this time the area of interest—the nature reserve—is given an initial value of zero:

Then, we create a new attrubute named count, with a value of 1 for each plant observation:

Finally, we rasterize the "count" attribute into the template raster, with an additional option options="MERGE_ALG=ADD". The "MERGE_ALG=ADD" option acts as a flag instructing st_rasterize to add up any overlapping attributes “burned” into the same pixel:

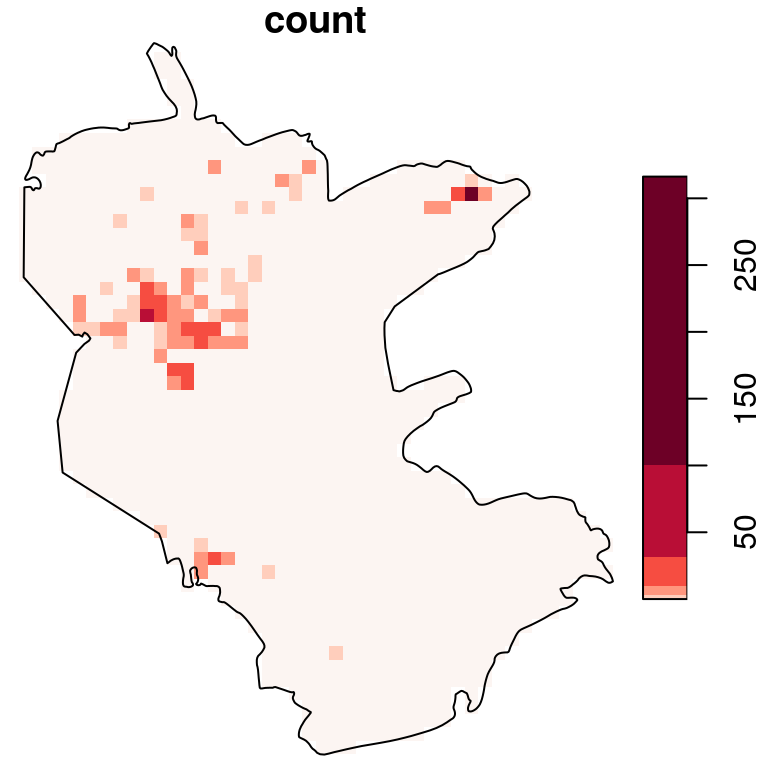

The resulting raster gives the number of rare plant observations per pixel (Figure 10.10):

plot(s, reset = FALSE, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(6, "Reds", rev = TRUE))

plot(st_geometry(reserve), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.10: Density (observations per pixel) of rare plants in the nature reserve

The raster coloring is almost uniform, because the distribution is highly skewed (try running hist(s[[1]])). We can use a logarithmic scale to visualize the density pattern more clearly (Figure 10.11):

b = c(0, 10^(seq(0, 2.5, 0.5)))

plot(s, breaks = b, reset = FALSE, col = hcl.colors(6, "Reds", rev = TRUE))

plot(st_geometry(reserve), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.11: Density (observations per pixel) of rare plants in the nature reserve, with a logarithmic scale

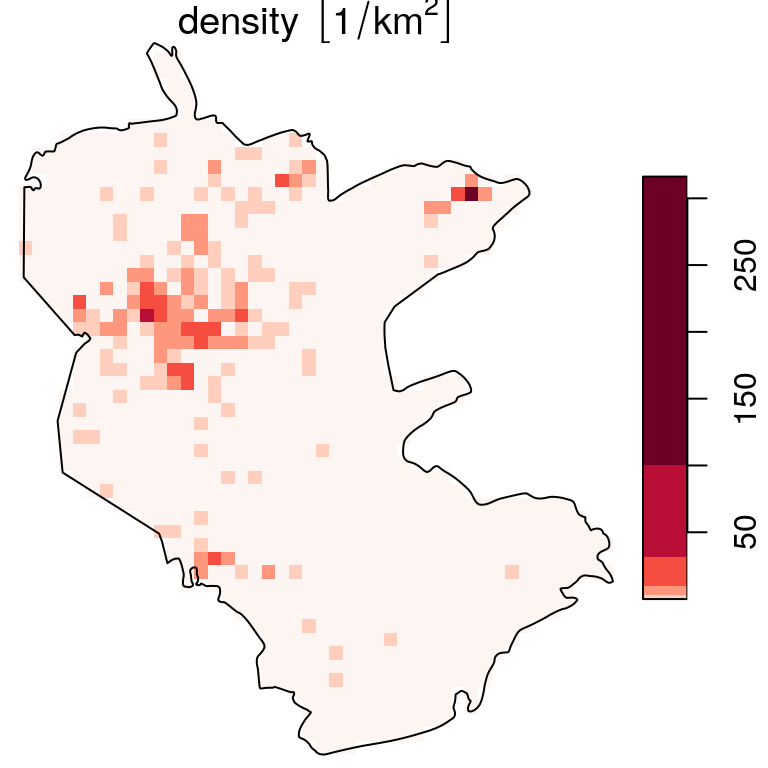

10.2.4 Standardizing density units

The units of measurement of the density raster are, at the moment, plants per pixel, which happens to have an area of 0.86 \(km^2\). We can find out the area of a pixel by applying the st_area function (Section 8.3.2.2) on the raster, which returns a raster of area values per pixel:

It is more convenient to work with counts per standard area unit, such as plants per 1 \(km^2\). To do that, we can calculate a raster with pixel areas a:

and then divide the plants count raster s by a:

The result is a raster with counts per unit area, in this case plant observations per \(km^2\) (Figure 10.12):

b = c(0, 10^(seq(0, 2.5, 0.5)))

plot(s, breaks = b, reset = FALSE, col = hcl.colors(6, "Reds", rev = TRUE))

plot(st_geometry(reserve), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.12: Density (observations per \(km^2\)) of rare plants in the nature reserve, with a logarithmic scale

10.3 Raster → Polygons

10.3.1 Raster to polygons conversion

The st_as_sf function makes the Raster→Polygons, using the (default) as_points=FALSE. The function ignores pixels that have a NA value in all layers. A useful option merge=TRUE dissolves all adjacent polygons that have the same raster value (in the first layer) into a single feature. The dissolve algorithm can be specified with the connect8 parameter: 4d, which is the default (connect8=FALSE) or 8d (connect8=TRUE). The attribute table of the polygon layer contains the raster values—with a separate attribute for each layer.

For example, let’s take a subset of the r:

- Rows 100-102

- Columns 200-202

- Layers 1-2

We will replace some of the pixel values with NA:

and also round the values to one digit:

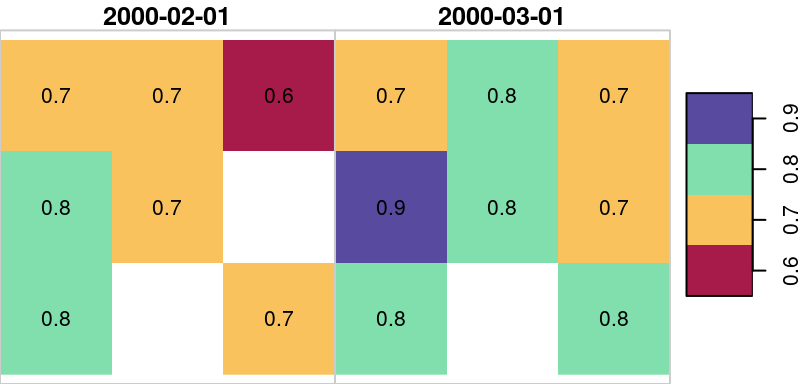

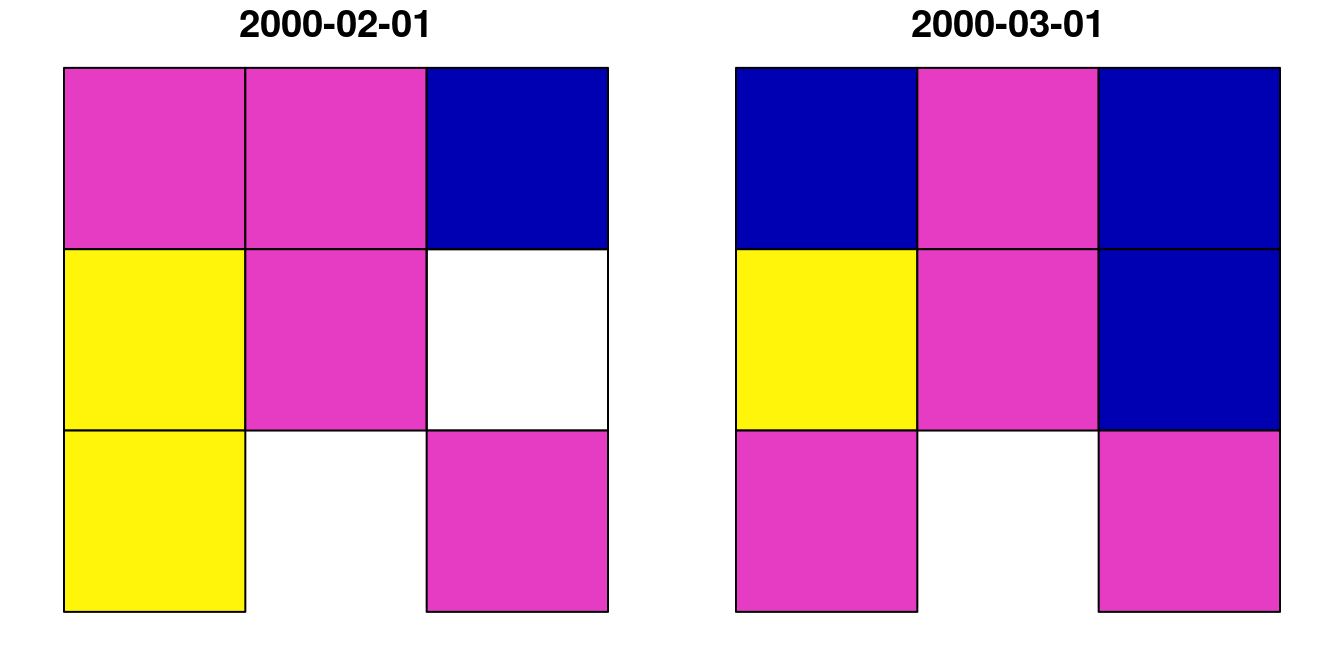

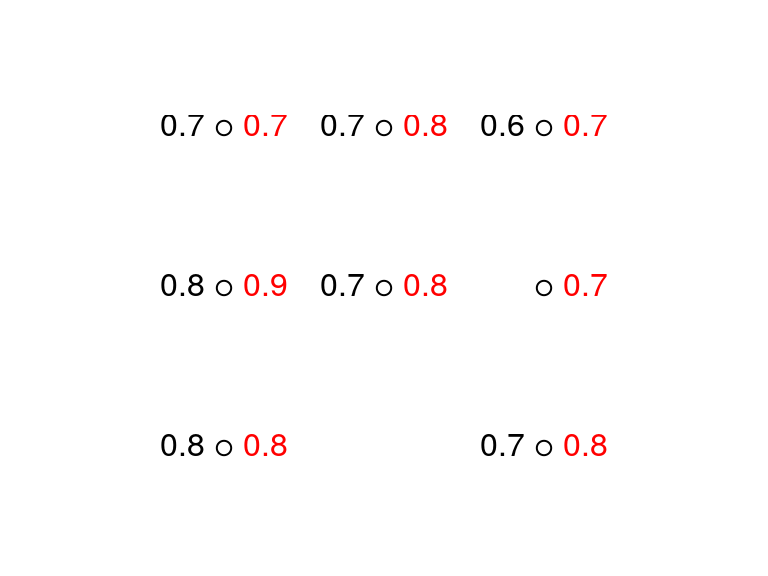

The resulting small raster u is visualized in Figure 10.13. Note that the raster has one pixel with NA in both layers and another pixel with NA in the first layer only.

Figure 10.13: Sample raster

Now, let’s transform the raster u to a polygon layer p, using st_as_sf:

The resulting polygonal layer p has 8 polygons, even though the raster u had 9 pixels. That is because one of the pixels had NA in all layers and therefore was not converted to a polygon:

p

## Simple feature collection with 8 features and 2 fields

## geometry type: POLYGON

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 727089 ymin: 3610119 xmax: 729867.9 ymax: 3612898

## CRS: +proj=utm +zone=36 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

## 2000-02-01 2000-03-01 geometry

## 1 0.7 0.7 POLYGON ((727089 3612898, 7...

## 2 0.7 0.8 POLYGON ((728015.3 3612898,...

## 3 0.6 0.7 POLYGON ((728941.6 3612898,...

## 4 0.8 0.9 POLYGON ((727089 3611972, 7...

## 5 0.7 0.8 POLYGON ((728015.3 3611972,...

## 6 NA 0.7 POLYGON ((728941.6 3611972,...

## 7 0.8 0.8 POLYGON ((727089 3611046, 7...

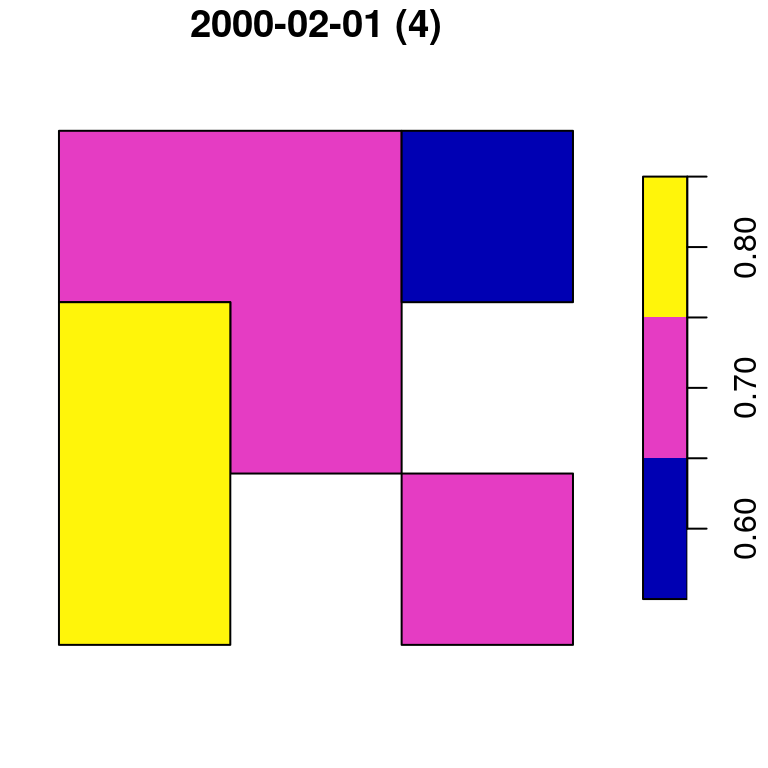

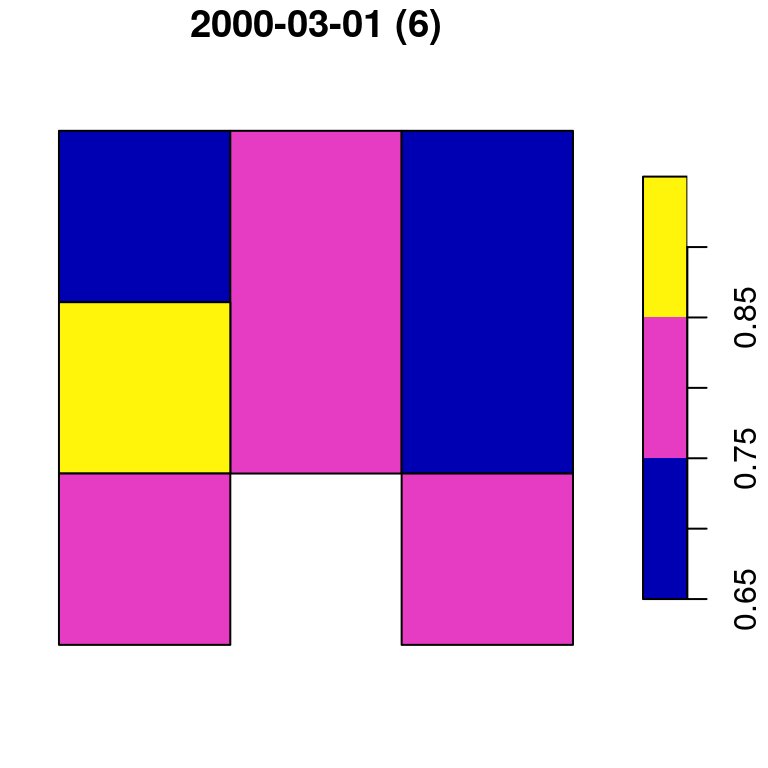

## 8 0.7 0.8 POLYGON ((728941.6 3611046,...The p layer is shown in Figure 10.14:

Figure 10.14: Polygon layer created from a raster

Let’s try the merge=TRUE option. Since merging is only affected by the first layer, it makes sense transform each of the layers separately:

As a result, we have two separate polygonal layers p1 and p2:

p1

## Simple feature collection with 4 features and 1 field

## geometry type: POLYGON

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 727089 ymin: 3610119 xmax: 729867.9 ymax: 3612898

## CRS: +proj=utm +zone=36 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

## NDVI geometry

## 1 0.7 POLYGON ((727089 3612898, 7...

## 2 0.6 POLYGON ((728941.6 3612898,...

## 3 0.8 POLYGON ((727089 3611972, 7...

## 4 0.7 POLYGON ((728941.6 3611046,...p2

## Simple feature collection with 6 features and 1 field

## geometry type: POLYGON

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 727089 ymin: 3610119 xmax: 729867.9 ymax: 3612898

## CRS: +proj=utm +zone=36 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

## NDVI geometry

## 1 0.7 POLYGON ((727089 3612898, 7...

## 2 0.8 POLYGON ((728015.3 3612898,...

## 3 0.7 POLYGON ((728941.6 3612898,...

## 4 0.9 POLYGON ((727089 3611972, 7...

## 5 0.8 POLYGON ((727089 3611046, 7...

## 6 0.8 POLYGON ((728941.6 3611046,...Figure 10.15 displays both p1 and p2:

plot(p1, main = paste0(colnames(p)[1], " (", nrow(p1), ")"))

plot(p2, main = paste0(colnames(p)[2], " (", nrow(p2), ")"))

Figure 10.15: Polygon layer created from a raster

Do you think there will there be a difference if we use

connect8=TRUE?

10.3.2 Example: segmentation

One example of a use case of raster to polygon conversion is the delineation of distinct inter-connected groups of pixels, sharing the same (or a similar) value. This operationis also known as segmentation. In it’s simplest form—detecting segments with exactly the same value—segmentation can be done using st_as_sf with merge=TRUE.

For example, we can derive segments of NDVI>0.2 in the reclassified NDVI raster l_rec_focal from Section 9.4.3. First, let’s recreate the l_rec_focal raster:

l = read_stars("landsat_04_10_2000.tif")

red = l[,,,3,drop=TRUE]

nir = l[,,,4,drop=TRUE]

ndvi = (nir - red) / (nir + red)

names(ndvi) = "NDVI"

l_rec = ndvi

l_rec[l_rec < 0.2] = 0

l_rec[l_rec >= 0.2] = 1

get_neighbors = function(m, pos) {

i = (pos[1]-1):(pos[1]+1)

j = (pos[2]-1):(pos[2]+1)

as.vector(t(m[i, j]))

}

focal2 = function(r, fun, ...) {

template = r

input = t(template[[1]])

output = matrix(NA, nrow = nrow(input), ncol = ncol(input))

for(i in 2:(nrow(input) - 1)) {

for(j in 2:(ncol(input) - 1)) {

v = get_neighbors(input, c(i, j))

output[i, j] = fun(v, ...)

}

}

template[[1]] = t(output)

return(template)

}

l_rec_focal = focal2(l_rec, max)Segments in the l_rec_focal raster represent distinct continuous areas with \(NDVI>0.2\). To detect them, we can convert the raster to polygons using st_as_sf with the merge=TRUE:

Then, we filter only those segments where raster value was 1:

The result is a polygon layer where each feature represents a single continuous area where \(NDVI>0.2\):

pol

## Simple feature collection with 536 features and 1 field

## geometry type: POLYGON

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 663975 ymin: 3459405 xmax: 687645 ymax: 3488145

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## First 10 features:

## NDVI geometry

## 1 1 POLYGON ((675615 3488145, 6...

## 2 1 POLYGON ((676455 3488145, 6...

## 5 1 POLYGON ((681945 3488145, 6...

## 8 1 POLYGON ((684765 3488145, 6...

## 12 1 POLYGON ((687195 3488145, 6...

## 13 1 POLYGON ((686985 3488085, 6...

## 17 1 POLYGON ((686505 3488145, 6...

## 18 1 POLYGON ((665865 3488145, 6...

## 23 1 POLYGON ((685545 3488145, 6...

## 26 1 POLYGON ((686835 3487905, 6...Figure 10.16) shows the segments on top of the NDVI raster:

plot(ndvi, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(11, "Spectral"), reset = FALSE)

plot(st_geometry(pol), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.16: Segments with NDVI>0.2

What is the exact number of segments in

pol? If we ran thest_as_sffunction onl_recinstead ofl_rec_focal, do you think the number of segments would be higher or lower?

10.4 Raster → Points

The Raster→Points transformation is done using function st_as_sf with the as_points=TRUE option. Pixel centers—except for pixels with NA in all layers—become points. The attribute table of the point layer contains the raster values.

For example, here is how we can transform the small raster u to a point layer:

The resulting point layer p has 8 points, even though the raster has 9 pixels, because one of the pixels had NA in all layers and therefore was not converted to a point:

p

## Simple feature collection with 8 features and 2 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 727552.1 ymin: 3610583 xmax: 729404.8 ymax: 3612435

## CRS: +proj=utm +zone=36 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

## 2000-02-01 2000-03-01 geometry

## 1 0.7 0.7 POINT (727552.1 3612435)

## 2 0.7 0.8 POINT (728478.4 3612435)

## 3 0.6 0.7 POINT (729404.8 3612435)

## 4 0.8 0.9 POINT (727552.1 3611509)

## 5 0.7 0.8 POINT (728478.4 3611509)

## 6 NA 0.7 POINT (729404.8 3611509)

## 7 0.8 0.8 POINT (727552.1 3610583)

## 8 0.7 0.8 POINT (729404.8 3610583)The point layer p is shown in Figure 10.17, with the first and second attribute values in black and in red, respectively:

plot(st_geometry(p))

text(st_coordinates(p), as.character(round(p$`2000-02-01`, 2)), pos = 2)

text(st_coordinates(p), as.character(round(p$`2000-03-01`, 2)), pos = 4, col = "red")

Figure 10.17: Point layer created from a raster

10.5 Distance to nearest point

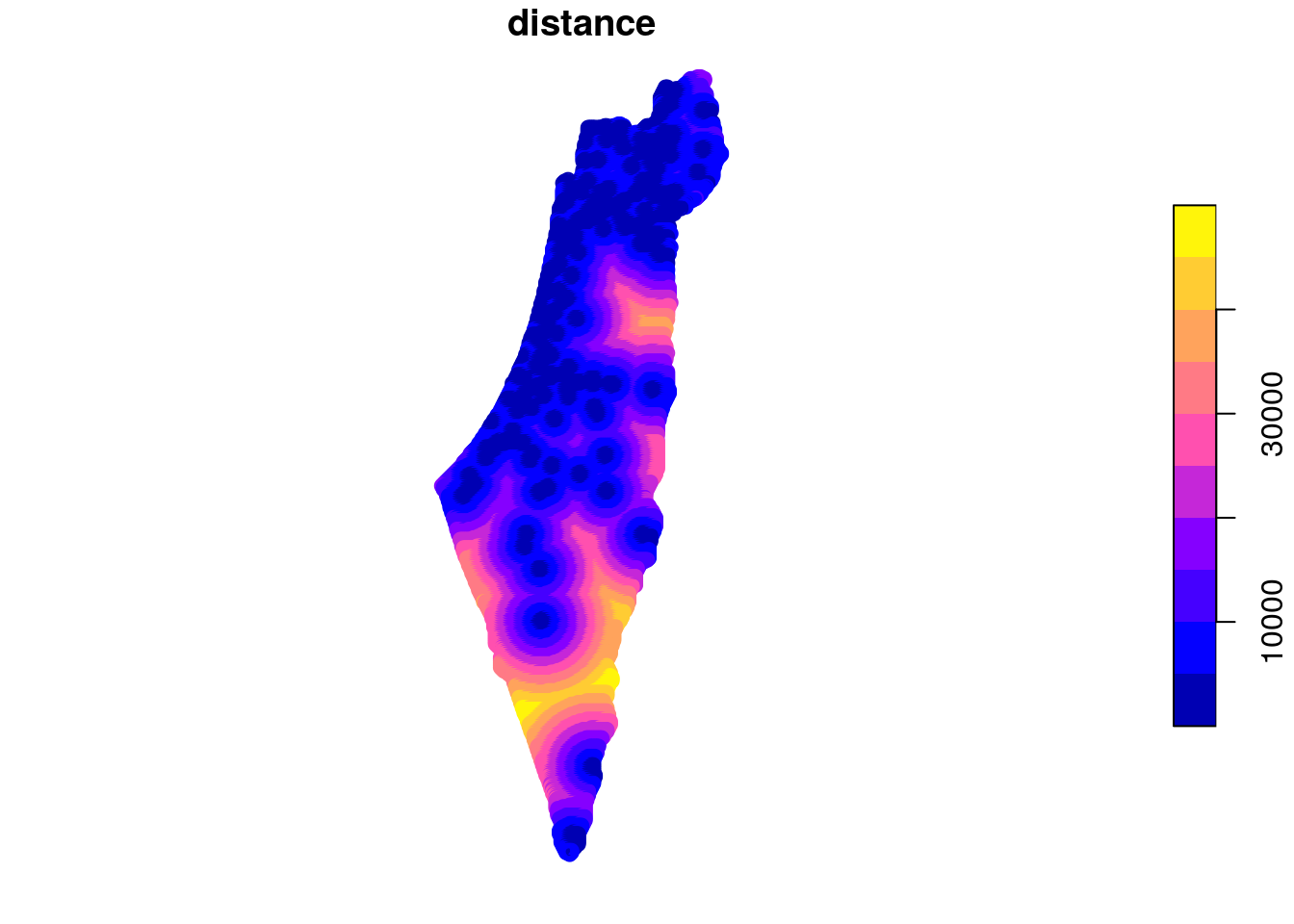

Another example of a spatial operator involving a raster and a vector layer is the calculation of a raster of distances to nearest point. For example, we may be interested in mapping the distances to nearest meteorological stations in Israel, perhaps to evaluate where coverage is too sparse and reliable meteorological data are missing.

Since the st_distance function (Section 8.3.2.3) expects vector layers as input, to calculate a raster of distances from nearest point we first need to convert the “template” raster to a point later. Our “template” for the distances raster, hereby grid is the \(926\times926\) \(m^2\) MODIS NDVI raster r_avg, but we could similarly use any other raster:

grid = st_as_sf(r_avg, as_points = TRUE)

grid$NDVI = NULL

grid

## Simple feature collection with 32858 features and 0 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 616395.6 ymin: 3262292 xmax: 770162.2 ymax: 3692097

## CRS: +proj=utm +zone=36 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

## First 10 features:

## geometry

## 1 POINT (757193.9 3691171)

## 2 POINT (758120.2 3691171)

## 3 POINT (759046.5 3691171)

## 4 POINT (753488.7 3690245)

## 5 POINT (754415 3690245)

## 6 POINT (755341.3 3690245)

## 7 POINT (756267.6 3690245)

## 8 POINT (757193.9 3690245)

## 9 POINT (758120.2 3690245)

## 10 POINT (759046.5 3690245)Given the grid point layer, we can use the st_distance to calculate pairwise distances between every grid point (grid) and meteorological station (rainfall):

rainfall = read.csv("rainfall.csv", stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

rainfall = st_as_sf(rainfall, coords = c("x_utm", "y_utm"), crs = 32636)

distance = st_distance(grid, rainfall)The result is a distance matrix named distance. Its rows correspond to grid points and its columns correspond to rainfall points:

In this example, we are interested in the minimal distance, per grid point, among the distances to the various meteorological stations. Therefore we apply the min function on the distance matrix rows, which refer to grid points. The result is a numeric vector of minimal distances, which we assign as an attribute in grid:

The grid point layer now has a new distance attribute:

grid

## Simple feature collection with 32858 features and 1 field

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 616395.6 ymin: 3262292 xmax: 770162.2 ymax: 3692097

## CRS: +proj=utm +zone=36 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

## First 10 features:

## geometry distance

## 1 POINT (757193.9 3691171) 15727.60

## 2 POINT (758120.2 3691171) 16408.58

## 3 POINT (759046.5 3691171) 17112.60

## 4 POINT (753488.7 3690245) 12556.66

## 5 POINT (754415 3690245) 13141.12

## 6 POINT (755341.3 3690245) 13763.17

## 7 POINT (756267.6 3690245) 14417.92

## 8 POINT (757193.9 3690245) 15101.13

## 9 POINT (758120.2 3690245) 15809.11

## 10 POINT (759046.5 3690245) 16538.68The distance attribute values reflect distance to nearest station, as is shown in Figure 10.18:

Figure 10.18: Distance to nearest meteorological station (point grid)

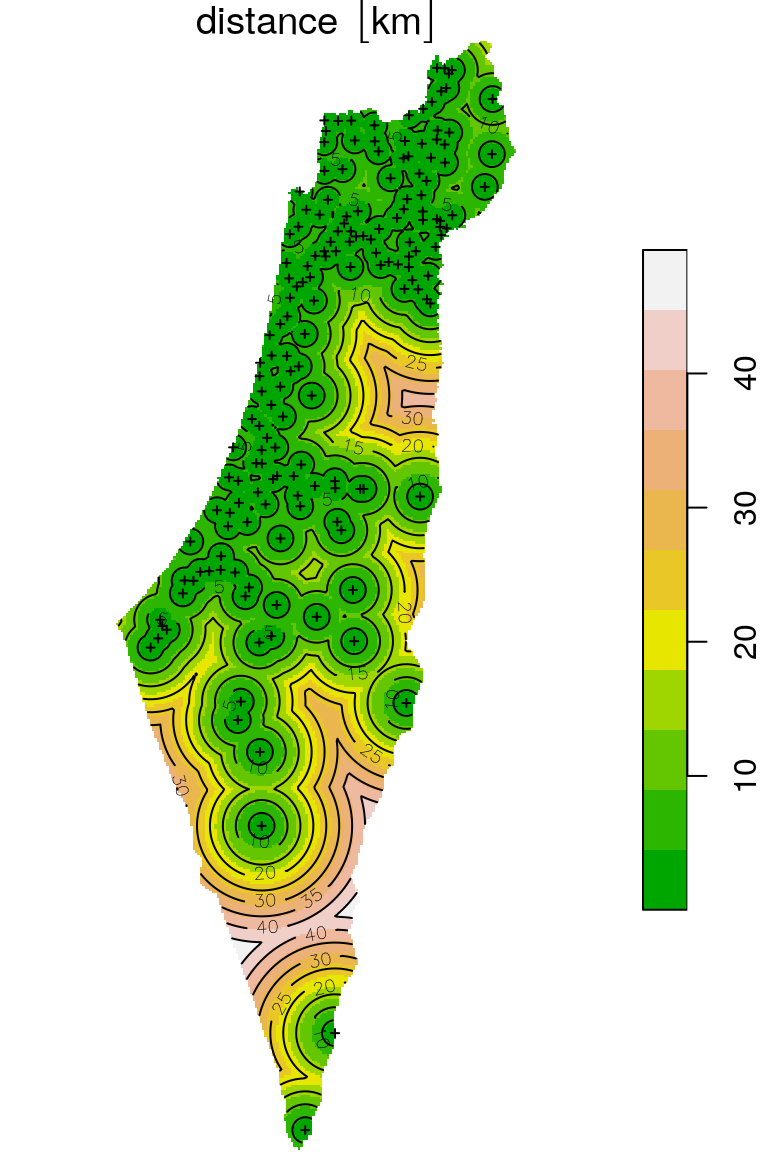

To have the results back as a raster, we can rasterize the points (Section 10.2). We use the same raster which we started with as template—this guarantees that every point corresponds exactly to one pixel:

It is also useful to set the raster value measurement units, for example to easily convert the distances from \(m\) to \(km\):

The final raster with distances to the nearest stations is shown in Figure 10.19. The locations of the meteorological stations and contour lines are shown on top of the raster, to emphasize the distance gradient.

plot(distance, breaks = "equal", col = terrain.colors(11), reset = FALSE)

plot(st_geometry(rainfall), add = TRUE, pch = 3, cex = 0.4)

contour(drop_units(distance), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.19: Distance to nearest meteorological station (raster)

10.6 Raster → Lines (contours)

We already saw how a raster can be converted to points or polygons, which simply results in a layer of cell centroids or outlines, respectively. Another common transformation is to calculate contour lines of equal raster values.

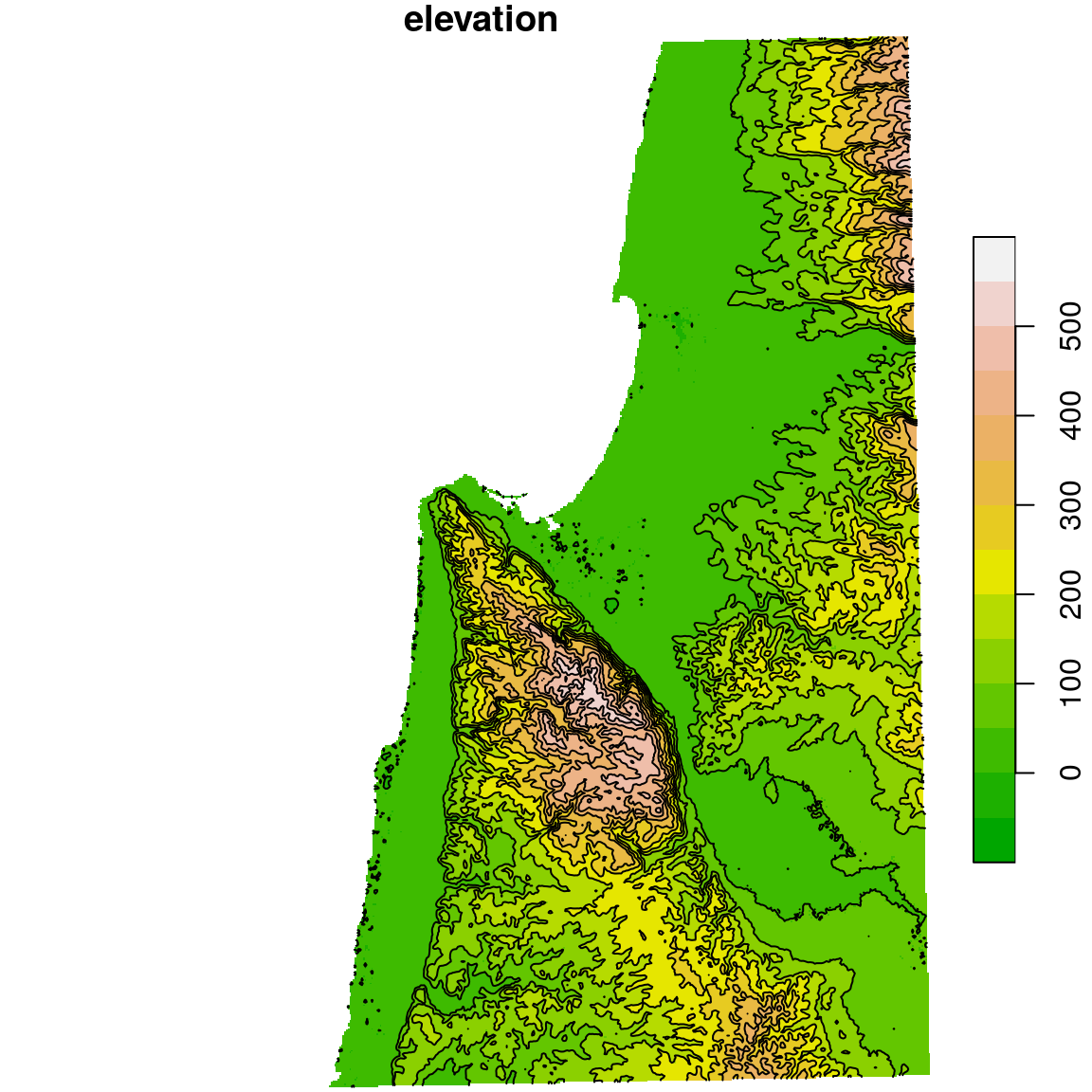

To illustrate contour lines calculation, we will reconstruct the Haifa DEM from Chapter 9:

dem1 = read_stars("_book/data/srtm_43_06.tif")

dem2 = read_stars("_book/data/srtm_44_06.tif")

dem = st_mosaic(dem1, dem2)

names(dem) = "elevation"

dem = dem[, 5687:6287, 2348:2948]

dem = st_normalize(dem)

dem = st_warp(src = dem, crs = 32636, method = "near", cellsize = 90)Raster contours can be created using the st_contour function. The function can accept a breaks argument, which determines the break points where contours are generated. Another parameter named contour_lines determines whether contours are returned as a line layer (TRUE) or polygon layer (FALSE, the default).

To decide on breaks values we are interested in, it is useful to examine the range of values in the raster:

According to the above result, we will use breaks from -100 to 600 meters, in steps of 50 meters:

The result, dem_contour, is a LINESTRING layer with one feature per contour line:

dem_contour

## Simple feature collection with 612 features and 1 field

## geometry type: LINESTRING

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 678607.1 ymin: 3602252 xmax: 710107.1 ymax: 3658412

## CRS: +proj=utm +zone=36 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

## First 10 features:

## elevation geometry

## 1 (100,150] LINESTRING (704500.1 365832...

## 2 (100,150] LINESTRING (704680.1 365832...

## 3 (150,200] LINESTRING (707113.3 365841...

## 4 (50,100] LINESTRING (701332.1 365823...

## 5 (300,350] LINESTRING (708883.5 365841...

## 6 (100,150] LINESTRING (706102.1 365802...

## 7 (50,100] LINESTRING (702198.3 365823...

## 8 (0,50] LINESTRING (700342.1 365746...

## 9 (150,200] LINESTRING (704932.1 365719...

## 10 (400,450] LINESTRING (709117.1 365728...The contours are shown in Figure 10.20:

plot(dem, breaks = b, col = terrain.colors(length(b)-1), key.pos = 4, reset = FALSE)

plot(st_geometry(dem_contour), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.20: Contour lines

10.7 Extracting raster values

10.7.1 Introduction

It is often necessary to “extract” raster values according to overlapping vector features, such as points, lines or polygons (Figure 10.21). For example, given an NDVI raster, we may be interested to calculate the NDVI value observed in particular point locations, or the average NDVI observed over an administrative area polygon.

Figure 10.21: Extracting raster values50

In the next few sections, we will see examples of extracting raster values:

10.7.2 Extracting to points: single-band

10.7.2.1 NDVI in meteorological stations

Raster values can be extracted to points by:

- Converting the raster to a polygon layer (Section 10.4); and then

- spatially joining the polygon attributes to the points (Section 8.1).

The spatial join is one-to-one, because each point falls in exactly one raster pixel (or none, if it is beyond raster extent)51.

For example, we can determine the average NDVI (r_avg) in the pixel where each meteorological station (rainfall) falls in as follows:

As a result, the rainfall layer now has an additional attribuite named NDVI:

rainfall

## Simple feature collection with 169 features and 13 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 629301.4 ymin: 3270290 xmax: 761589.2 ymax: 3681163

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## First 10 features:

## num altitude sep oct nov dec jan feb mar apr may name

## 1 110050 30 1.2 33 90 117 135 102 61 20 6.7 Kfar Rosh Hanikra

## 2 110351 35 2.3 34 86 121 144 106 62 23 4.5 Saar

## 3 110502 20 2.7 29 89 131 158 109 62 24 3.8 Evron

## 4 111001 10 2.9 32 91 137 152 113 61 21 4.8 Kfar Masrik

## 5 111650 25 1.0 27 78 128 136 108 59 21 4.7 Kfar Hamakabi

## 6 120202 5 1.5 27 80 127 136 95 49 19 2.7 Haifa Port

## 7 120630 450 1.9 36 93 161 166 128 71 21 4.9 Haifa University

## 8 120750 30 1.6 31 91 163 170 146 76 22 4.9 Yagur

## 9 120870 210 1.1 32 93 147 147 109 61 16 4.3 Nir Etzyon

## 10 121051 20 1.8 32 85 147 142 102 56 13 4.5 En Carmel

## NDVI geometry

## 1 0.4357747 POINT (696533.1 3660837)

## 2 0.3544532 POINT (697119.1 3656748)

## 3 0.3196541 POINT (696509.3 3652434)

## 4 0.4238691 POINT (696541.7 3641332)

## 5 0.3745760 POINT (697875.3 3630156)

## 6 NA POINT (687006.2 3633330)

## 7 0.4580601 POINT (689553.7 3626282)

## 8 0.3732974 POINT (694694.5 3624388)

## 9 0.5153764 POINT (686489.5 3619716)

## 10 0.4521039 POINT (683148.4 3616846)The attribute values are shown as text labels in Figure 10.22:

plot(r_avg, breaks = "equal", col = hcl.colors(11, "Spectral"), reset = FALSE)

text(st_coordinates(rainfall), as.character(round(rainfall$NDVI, 2)), cex = 0.5)

Figure 10.22: Raster values extracted to points

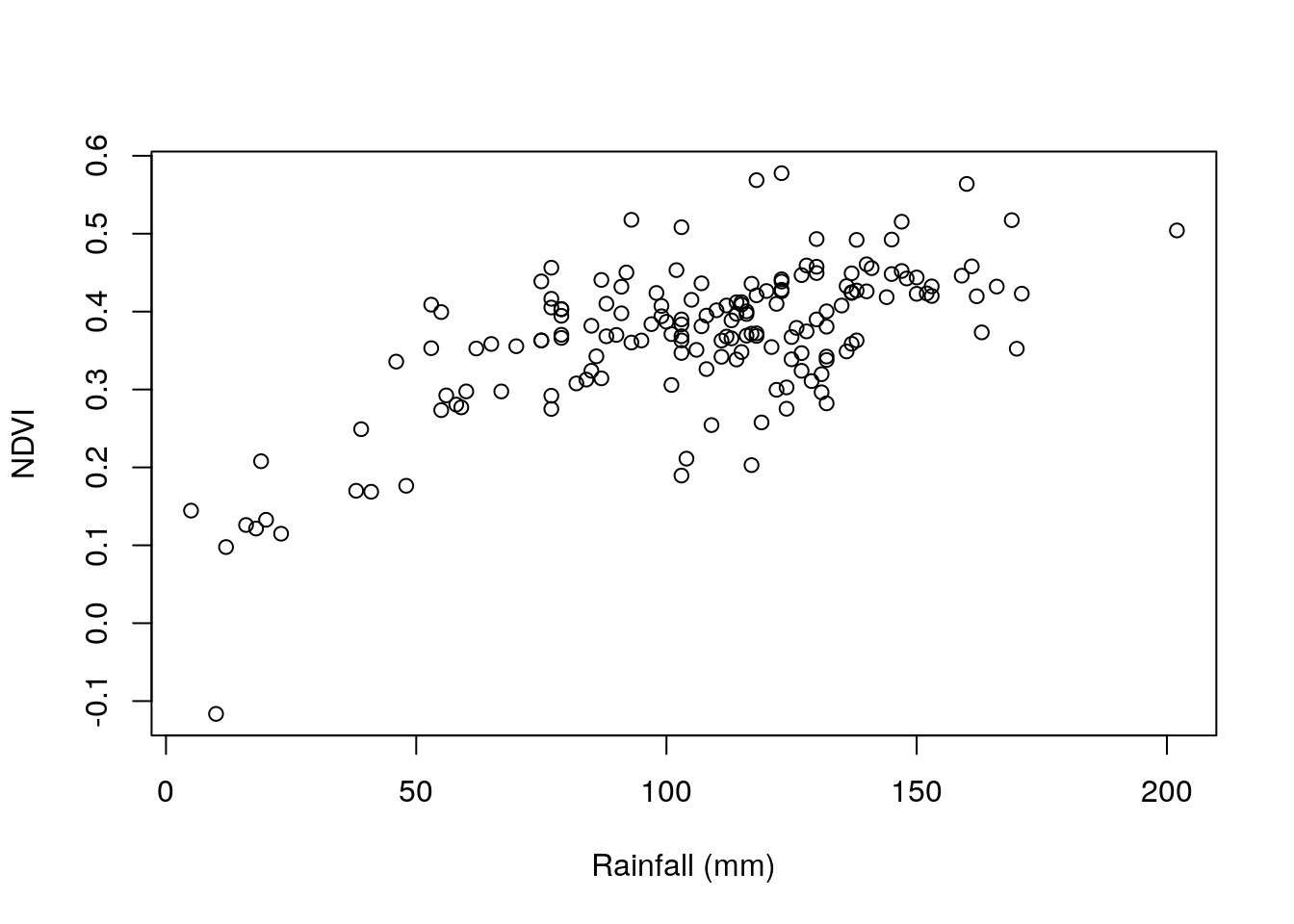

Now that we know the average NDVI for each meteorological station location, we can examine, for instance, the association between NDVI and rainfall in December (Figure 10.23):

Figure 10.23: Average NDVI as function of average rainfall in December

What is the number and proportion of

rainfallpoints that have anNAvalue in theNDVIattribute? Why did those stations getNA?

10.7.2.2 Elevation along GPS track

The following example uses a GPX (GPS Exchange Format) file. A GPX file contains one or more layers, of the following types:

waypointstracks(recorder track as line)routestrack_points(recorder track as points)route_points

When reading a file format that contains more than one layer, such as GPX, we may first need to find out which layers the file contains. This can be done using st_layers:

which returns the list of layers contained in the GPX file:

## Driver: GPX

## Available layers:

## layer_name geometry_type features fields

## 1 waypoints Point 0 23

## 2 routes Line String 0 12

## 3 tracks Multi Line String 1 13

## 4 route_points Point 0 25

## 5 track_points Point 5091 26Once we know which layer we want to read, we can specify at as the second argument in st_read:

Next, we will prepare a \(1\times1\) \(km^2\) elevation raster named dem1km. The methods we use should be familiar from Chapter 9:

dem1 = read_stars("_book/data/srtm_43_06.tif")

dem2 = read_stars("_book/data/srtm_44_06.tif")

dem = st_mosaic(dem1, dem2)

names(dem) = "elevation"

grid = st_transform(st_as_sfc(st_bbox(dem)), st_crs(32636))

grid = st_as_stars(grid, dx = 1000, dy = 1000)

dem1km = st_warp(dem, grid, method = "average", use_gdal = TRUE)

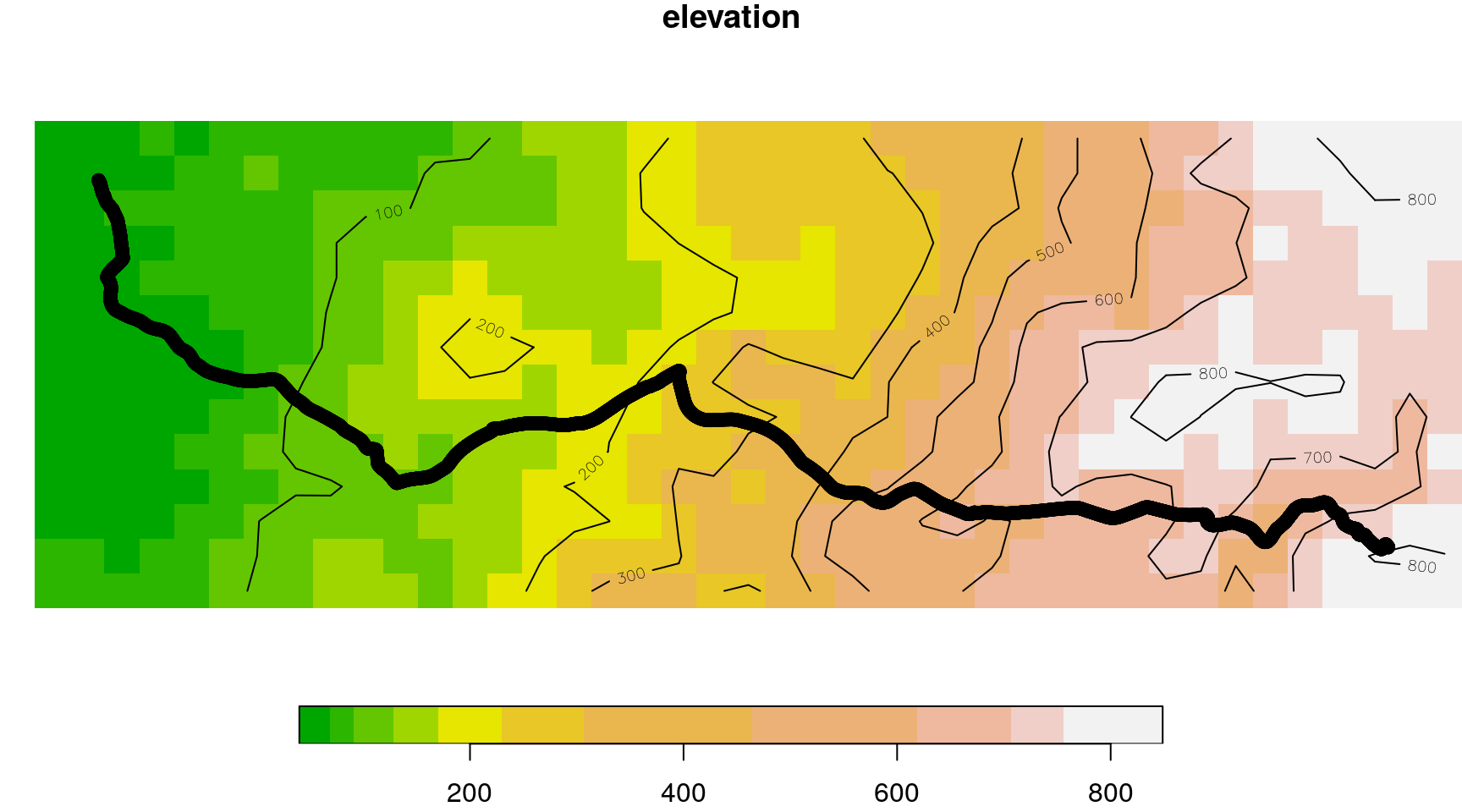

names(dem1km) = "elevation"We will also reproject the track point layer to UTM and crop the raster according to its extent, plus a 2 \(km\) buffer:

track = st_transform(track, 32636)

ext = st_as_sfc(st_bbox(st_buffer(track, 2000)))

dem1km = dem1km[ext]The elevation raster and the GPS track are shown in Figure 10.24:

plot(dem1km, col = terrain.colors(11), reset = FALSE)

contour(dem1km, add = TRUE)

plot(st_geometry(track), add = TRUE)

Figure 10.24: GPS track and elevation

To extract the elevation values per GPS point, we convert the raster to a polygon layer, then join the polygon attributes (elevation) with the track point:

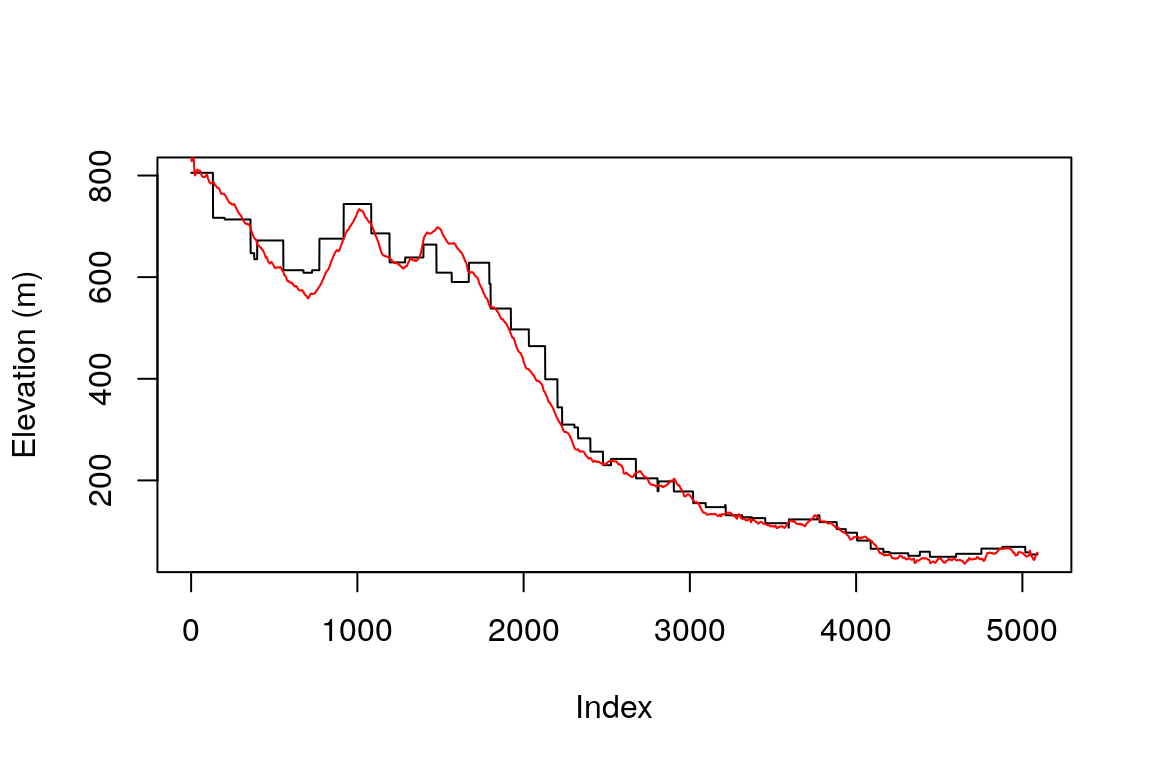

The track layer contains a field named ele, which contains elevation recorded by the GPS device. Figure 10.25 shows the elevation profile recorded by the GPS (ele, in red) and the elevation profile extracted from the DEM (elevation, in black):

Figure 10.25: Elevation profile, based on GPS measurements (in red) and a DEM raster (in black)

What is the reason for the stairs-like shape of the black line in Figure 10.25?

10.7.3 Extracting to points: multi-band

As another example, we can extract the NDVI values for different dates from the multi-band raster r. For simplicity, let’s create a subset rainfall1, with just three meteorological stations from the rainfall layer:

Also, we will remove all non-spatial attributes, by creating a new sf layer with nothing but the geometry from rainfall1:

rainfall1 = st_sf(geometry = st_geometry(rainfall1))

rainfall1

## Simple feature collection with 3 features and 0 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 671364.1 ymin: 3307819 xmax: 717491.2 ymax: 3648872

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## geometry

## 1 POINT (717491.2 3648872)

## 2 POINT (671364.1 3458877)

## 3 POINT (700626.3 3307819)To extract the NDVI values from the first five bands of r, we transform the raster to a polygon layer and perform a spatial join:

As a result, five new attributes were joined:

rainfall1

## Simple feature collection with 3 features and 5 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 671364.1 ymin: 3307819 xmax: 717491.2 ymax: 3648872

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## 2000-02-01 2000-03-01 2000-04-01 2000-05-01 2000-06-01

## 1 0.4314 0.4485 0.5396 0.5234 0.4772

## 2 NA 0.1587 0.1618 0.1541 0.1489

## 3 0.1440 0.1254 0.1251 0.1122 0.1092

## geometry

## 1 POINT (717491.2 3648872)

## 2 POINT (671364.1 3458877)

## 3 POINT (700626.3 3307819)To work with the data, we can rearrange them to a more convenient form. For example, the geometry column can be discarded:

rainfall1 = st_drop_geometry(rainfall1)

rainfall1

## 2000-02-01 2000-03-01 2000-04-01 2000-05-01 2000-06-01

## 1 0.4314 0.4485 0.5396 0.5234 0.4772

## 2 NA 0.1587 0.1618 0.1541 0.1489

## 3 0.1440 0.1254 0.1251 0.1122 0.1092Then, we can rely on the fact that row and column order matches the vector layer feature and raster layer order, respectively, to assign names. For example, rainfall1 rows correspond to the selected station names:

rownames(rainfall1) = sel

rainfall1

## 2000-02-01 2000-03-01 2000-04-01 2000-05-01 2000-06-01

## Horashim 0.4314 0.4485 0.5396 0.5234 0.4772

## Beer Sheva NA 0.1587 0.1618 0.1541 0.1489

## Yotveta 0.1440 0.1254 0.1251 0.1122 0.1092Columns in

rainfall1are already named according to image dates. Where did these names come from?

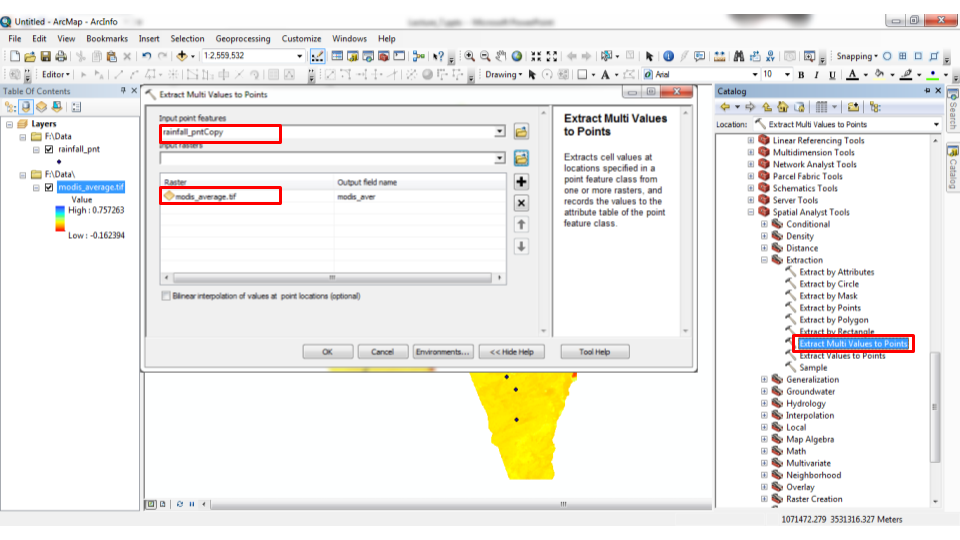

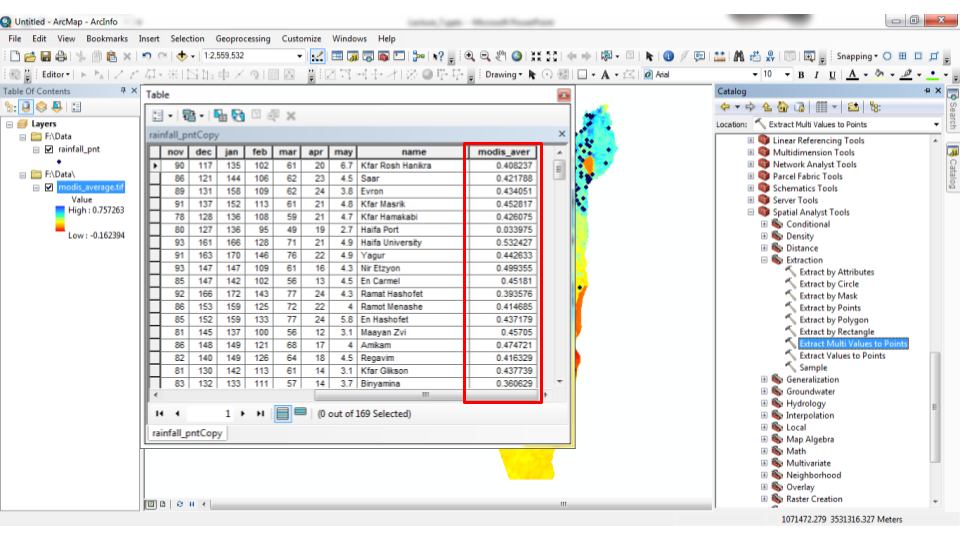

The analogous operation in ArcGIS is the “Extract Multi Values to Points” tool (Figures 10.26–10.27).

Figure 10.26: “Extract Multi Values to Points” tool in ArcGIS

Figure 10.27: “Extract Multi Values to Points” tool in ArcGIS

10.7.4 Extracting to polygons: single-band

Extracting raster values to polygons (or to lines) is different from extracting to points. When extracting raster values to polygons (or to lines), each vector feature is potentially associated with more than one pixel value (Figure 10.21). Moreover, the number of pixels may vary between features. For example, a large polygon may cover many more pixels than a small polygon. Therefore, it is often convenient to summarize the raster values per polygon feauture by applying a function on them and obtaining a single number, such as the average. This is done by aggregating the raster based on a vector layer using function aggregate52.

When summarizing raster values per polygon feature, the aggregate function accepts53:

x—Thestarsraster to summarizeby—Ansflayer determining areasFUN—The function to be applied on each set of extracted pixel values fromx

For example, we can calculate the average (mean) NDVI value (r_avg) per administrative area (nafot) as follows:

The result is a special type of a stars object, with just one dimension for the vector geometries:

ndvi_nafot

## stars object with 1 dimensions and 1 attribute

## attribute(s):

## NDVI

## Min. :0.1263

## 1st Qu.:0.3376

## Median :0.3845

## Mean :0.3554

## 3rd Qu.:0.4001

## Max. :0.4317

## dimension(s):

## from to offset delta refsys point

## geometry 1 15 NA NA WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N FALSE

## values

## geometry POLYGON ((739780.1 3686007,...,...,POLYGON ((674110.3 3549169,...It can be converted to the more familiar sf structure using st_as_sf:

Now we have a polygon layer of the administrative areas, with an NDVI attribute containing the average NDVI value according to the r_avg raster:

ndvi_nafot

## Simple feature collection with 15 features and 1 field

## geometry type: POLYGON

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 620662.1 ymin: 3263494 xmax: 770624.4 ymax: 3691834

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## First 10 features:

## NDVI geometry

## 1 0.4208889 POLYGON ((739780.1 3686007,...

## 2 0.3845475 POLYGON ((672273.8 3518394,...

## 3 0.3093089 POLYGON ((745560 3649860, 7...

## 4 0.3874892 POLYGON ((702283.1 3628046,...

## 5 0.4317472 POLYGON ((702725.9 3630513,...

## 6 0.4051780 POLYGON ((759304.4 3691202,...

## 7 0.3949261 POLYGON ((701391.6 3631170,...

## 8 0.4124200 POLYGON ((706537.1 3602188,...

## 9 0.3937370 POLYGON ((692687.3 3583974,...

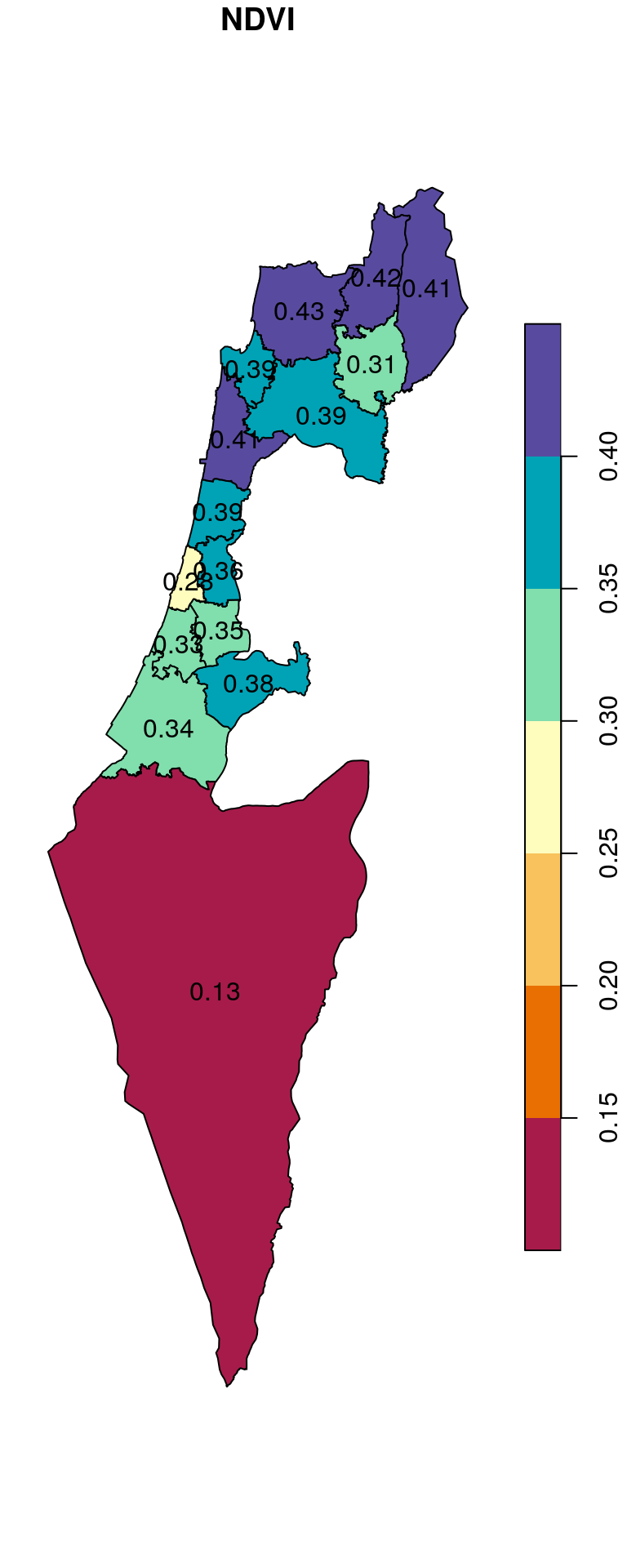

## 10 0.3468470 POLYGON ((672841.5 3544808,...The result can be visualized as follows (Figure 10.28):

plot(ndvi_nafot, pal = function(x) hcl.colors(x, "Spectral"), reset = FALSE, key.pos = 4)

text(st_coordinates(st_centroid(ndvi_nafot)), as.character(round(ndvi_nafot$NDVI, 2)))

Figure 10.28: Average NDVI per “Nafa”

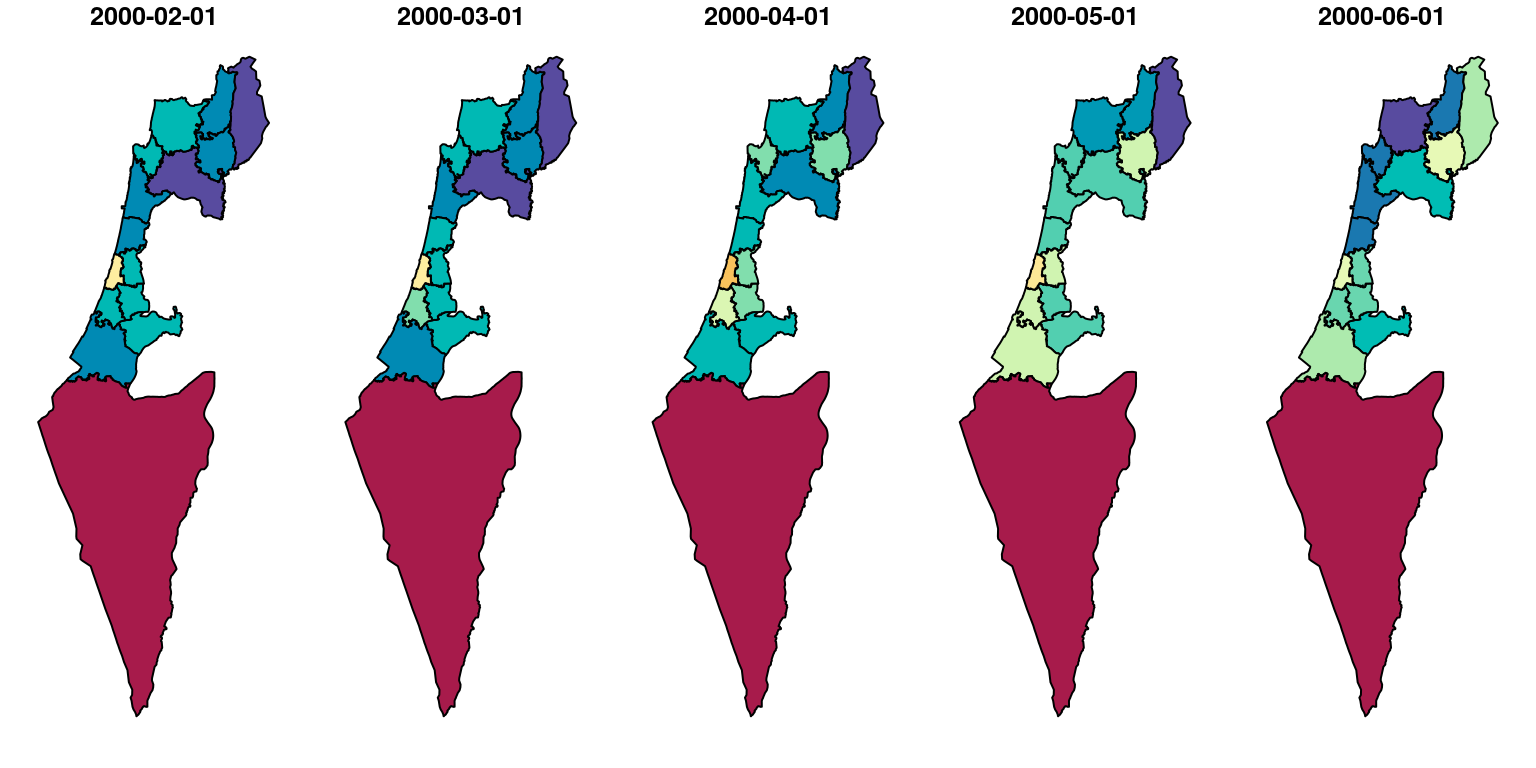

10.7.5 Extracting to polygons: multi-band

Extracting raster values from a multi-band raster works the same way as extracting from a multi-band raster. The difference is that the resulting stars object has two dimensions: one for the geometries and one for the input raster bands.

For example, the following expression calculates the average r value for each nafot feature over five months starting from 2000-02-01, based on the first five layers of r:

ndvi_nafot = aggregate(r[,,,1:5], nafot, FUN = mean, na.rm = TRUE)

ndvi_nafot

## stars object with 2 dimensions and 1 attribute

## attribute(s):

## NDVI

## Min. :0.1083

## 1st Qu.:0.3148

## Median :0.4408

## Mean :0.4023

## 3rd Qu.:0.4873

## Max. :0.5906

## dimension(s):

## from to offset delta refsys point

## geometry 1 15 NA NA WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N FALSE

## time 1 5 NA NA Date NA

## values

## geometry POLYGON ((739780.1 3686007,...,...,POLYGON ((674110.3 3549169,...

## time 2000-02-01,...,2000-06-01When transformed to an sf layer, the values extracted from each raster layer are placed in separate attributes:

ndvi_nafot = st_as_sf(ndvi_nafot)

ndvi_nafot

## Simple feature collection with 15 features and 5 fields

## geometry type: POLYGON

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 620662.1 ymin: 3263494 xmax: 770624.4 ymax: 3691834

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## First 10 features:

## 2000-02-01 2000-03-01 2000-04-01 2000-05-01 2000-06-01

## 1 0.5061847 0.5270644 0.5319248 0.4432705 0.3478298

## 2 0.4692342 0.4604232 0.4568367 0.3757161 0.3096993

## 3 0.5395486 0.5398781 0.4491296 0.3011687 0.2440450

## 4 0.5616802 0.5826193 0.5475469 0.3978501 0.3062216

## 5 0.4718739 0.4840480 0.4993016 0.4304506 0.3796581

## 6 0.5518223 0.5851435 0.5905808 0.4905159 0.2675451

## 7 0.4593590 0.4520991 0.4388301 0.3730517 0.3468060

## 8 0.5061774 0.5087029 0.4809899 0.3971890 0.3509476

## 9 0.5104205 0.4970106 0.4763348 0.3797437 0.3421975

## 10 0.4709000 0.4675206 0.4407848 0.3536589 0.2844259

## geometry

## 1 POLYGON ((739780.1 3686007,...

## 2 POLYGON ((672273.8 3518394,...

## 3 POLYGON ((745560 3649860, 7...

## 4 POLYGON ((702283.1 3628046,...

## 5 POLYGON ((702725.9 3630513,...

## 6 POLYGON ((759304.4 3691202,...

## 7 POLYGON ((701391.6 3631170,...

## 8 POLYGON ((706537.1 3602188,...

## 9 POLYGON ((692687.3 3583974,...

## 10 POLYGON ((672841.5 3544808,...The result reflects the average NDVI, for the first five months in the MODIS NDVI series, for each “Nafa” (Figure 10.29):

Figure 10.29: NDVI per “Nafa” for five months

In rare cases, the point may fall exactly on the border between two raster pixels, in which case it will be joined to two different raster values. Therefore, to be safe, the join result may be filtered to remove duplicated points.↩

Recall that we already used

aggregatefor a different use case: dissolving vector layers by attribute (Section 8.4).↩Note that using

aggregateto extract raster values by polygons is only appropriate for non-overlapping polygons. For polygons that are potentially overlapping, useraster::extract.↩