Chapter 7 Vector layers

Last updated: 2020-08-12 00:36:37

Aims

Our aims in this chapter are:

- Become familiar with data structures for vector layers: points, lines and polygons

- Examine spatial and non-spatial properties of vector layers

- Create subsets of vector layers based on their attributes

- Learn to transform a layer from one Coordinate Reference System (CRS) to another

We will use the following R packages:

sfmapviewstars

7.1 Vector layers

7.1.1 What is a vector layer?

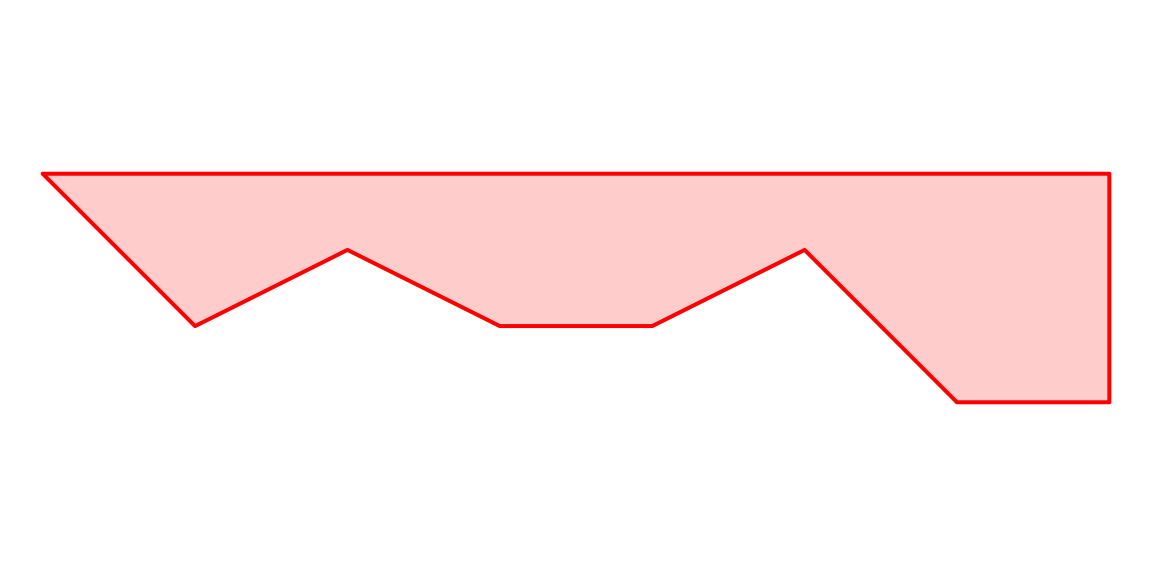

Vector layers are essentially sets of geometries associated with non-spatial attributes (Figure 7.1). The geometries are sequences of one or more point coordinates, possibly connected to form lines or polygons. The non-spatial attributes come in the form of a table.

![Geometry (left) and non-spatial attributes (right) of vector layers^[https://www.neonscience.org/dc-shapefile-attributes-r]](images/vector_layers.png)

Figure 7.1: Geometry (left) and non-spatial attributes (right) of vector layers32

7.1.2 Vector file formats

Commonly used vector layer file formats (Table 7.1) include binary formats (such as the Shapefile) and plain text formats (such as GeoJSON). Vector layers are also frequently kept in a spatial database, such as PostgreSQL/PostGIS.

| Type | Format | File extension |

|---|---|---|

| Binary | ESRI Shapefile | .shp, .shx, .dbf, .prj, … |

| GeoPackage (GPKG) | .gpkg |

|

| Plain Text | GeoJSON | .json or .geojson |

| GPS Exchange Format (GPX) | .gpx |

|

| Keyhole Markup Language (KML) | .kml |

|

| Spatial Databases | PostGIS / PostgreSQL |

7.1.3 Vector data structures (sp)

The first R package to establish a uniform vector layer class system was sp, released in 2005 (Figure 7.2). Together with rgdal and rgeos, this package dominated the landscape of spatial analysis in R for many years (Figure 7.3).

![Pebesma & Bivand, 2005, R News^[https://journal.r-project.org/archive/r-news.html]](images/lesson_07_paper2.png)

Figure 7.2: Pebesma & Bivand, 2005, R News33

![The network structure of CRAN; `sp` ecosystem shown in green^[blog.revolutionanalytics.com/2015/07/the-network-structure-of-cran.html]](images/cran_graph.png)

Figure 7.3: The network structure of CRAN; sp ecosystem shown in green34

Package sp has 6 main classes for vector layers (Table 7.2):

- One for each geometry type (points, lines, polygons)

- One for geometry only and one for geometry with attributes

| Class | Geometry type | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

SpatialPoints |

Points | - |

SpatialPointsDataFrame |

Points | data.frame |

SpatialLines |

Lines | - |

SpatialLinesDataFrame |

Lines | data.frame |

SpatialPolygons |

Polygons | - |

SpatialPolygonsDataFrame |

Polygons | data.frame |

7.1.4 Vector data structures (sf)

Package sf, released in 2016 (Figure 7.4), is a newer package for working with vector layers in R, which we are going to use in this book.

![Pebesma, 2018, The R Journal^[https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2018-1/]](images/lesson_07_paper1.png)

Figure 7.4: Pebesma, 2018, The R Journal35

Package sf defines a hierarchical class system with three classes (Table 7.3):

- Class

sfgis for a single geometry - Class

sfcis a set of geometries with a CRS - Class

sfis a layer with attributes

| Class | Hierarchy | Data |

|---|---|---|

sfg |

Geometry | type, coordinates |

sfc |

Geometry column | set of sfg + CRS |

sf |

Layer | sfc + attributes |

7.1.5 Vector layers in R: package sf

sf is a relative new (2016-) R package for handling vector layers in R. In the long-term, sf aims to replace rgdal (2003-), sp (2005-), and rgeos (2011-).

The main innovation in sf is a complete implementation of the Simple Features standard. Since 2003, Simple Features been widely implemented in spatial databases (such as PostGIS), commercial GIS (e.g., ESRI ArcGIS) and forms the vector data basis for libraries such as GDAL. When working with spatial databases, Simple Features are commonly specified as Well Known Text (WKT). A subset of simple features forms the GeoJSON standard.

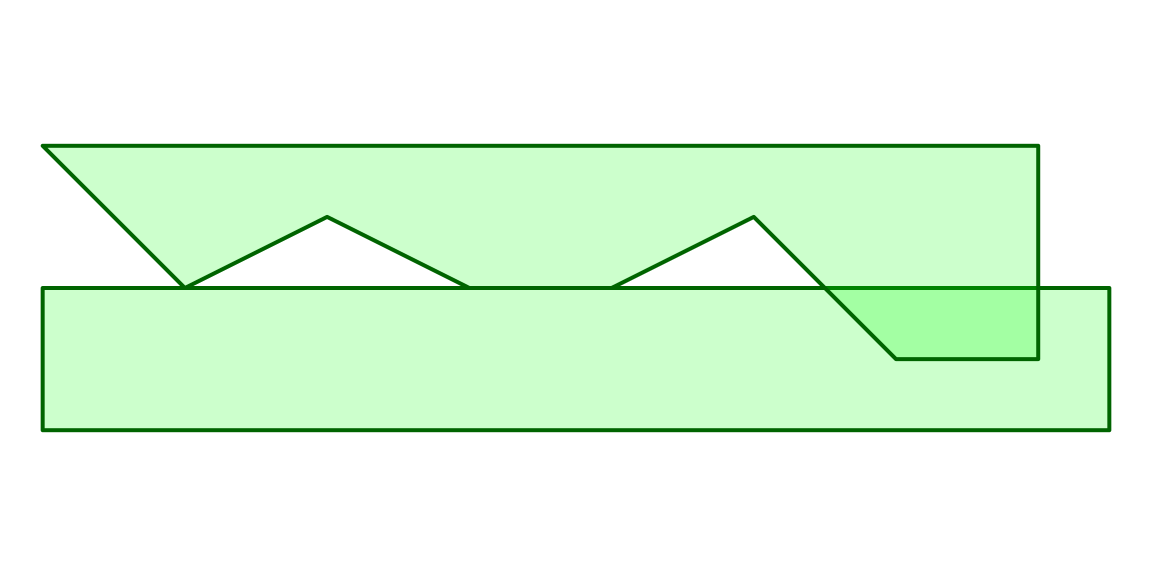

It is important to note that the sf package depends on several external software components (installed along with the R package), most importantly GDAL, GEOS and PROJ (Figure 7.5). These well-tested and popular open-source components are common to numerous open-source and commercial software for spatial analysis, such as QGIS and PostGIS.

![`sf` package dependencies^[https://github.com/edzer/rstudio_conf]](images/sf_deps.png)

Figure 7.5: sf package dependencies36

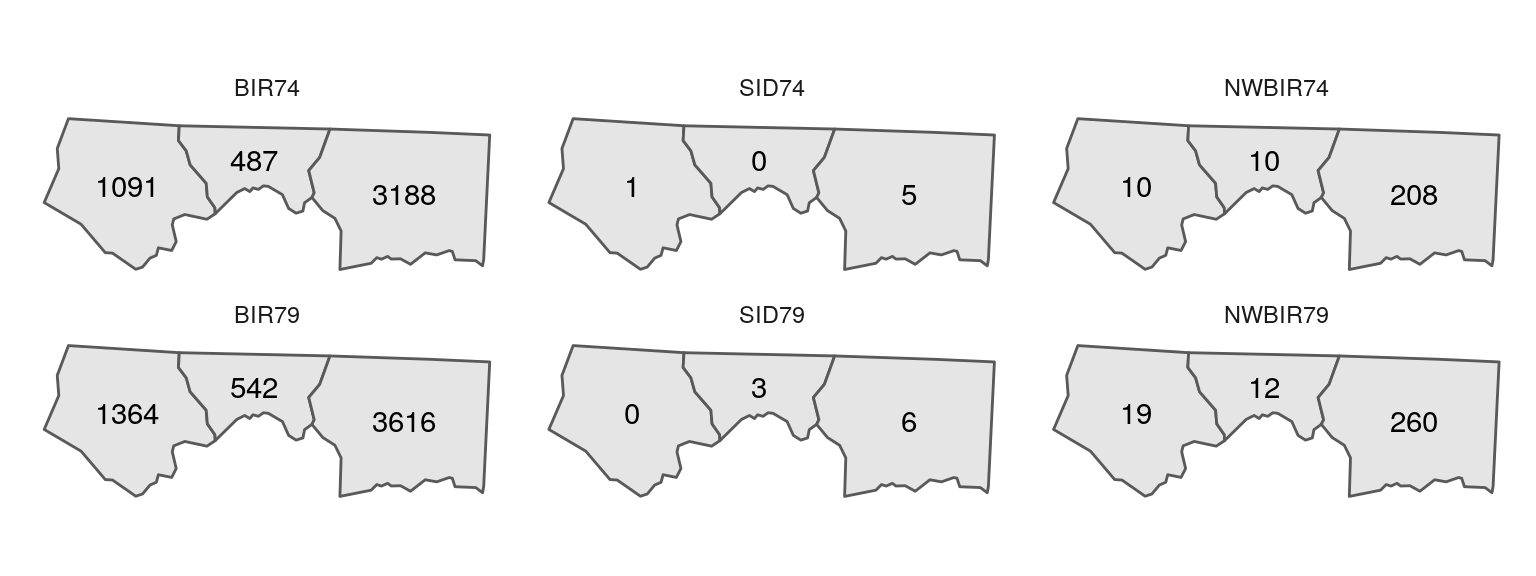

The sf class extends the data.frame class to include a geometry column. This is similar to the way that spatial databases are structured. For example, the sample dataset shown in Figure 7.6 represents a polygonal layer with three features and six non-spatial attributes. The attributes refer to demographic and epidemiological attributes of US counties, such as the number of births in 1974 (BIR74), the number of sudden infant death cases in 1974 (SID74), and so on. The seventh column is the geometry column, containing the polygon geometries.

![Structure of an `sf` object^[https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sf/vignettes/sf1.html]](images/sf.png)

Figure 7.6: Structure of an sf object37

Figure 7.7 shows what layer in Figure 7.6 would look like when mapped. We can see the outline of the three polygons, as well as the values of all six non-spatial attributes (in separate panels).

Figure 7.7: Visualization of the sf object shown in Figure 7.6

The sf class is actually a hierarchical structure composed of three classes:

sf—Vector layer object, a table (data.frame) with one or more attribute columns and one geometry columnsfc—Geometric part of the vector layer, the geometry columnsfg—Geometry of an individual simple feature

7.2 Vector layers from scratch

Let’s create a sample object for each of these classes to learn more about them.

Objects of class sfg, i.e., a single geometry, can be created using the appropriate function for each geometry type:

st_pointst_multipointst_linestringst_multilinestringst_polygonst_multipolygonst_geometrycollection

from coordinates passed as:

numericvectors—POINTmatrixobjects—MULTIPOINTorLINESTRINGlistobjects—All other geometries

7.2.1 Geometry (sfg)

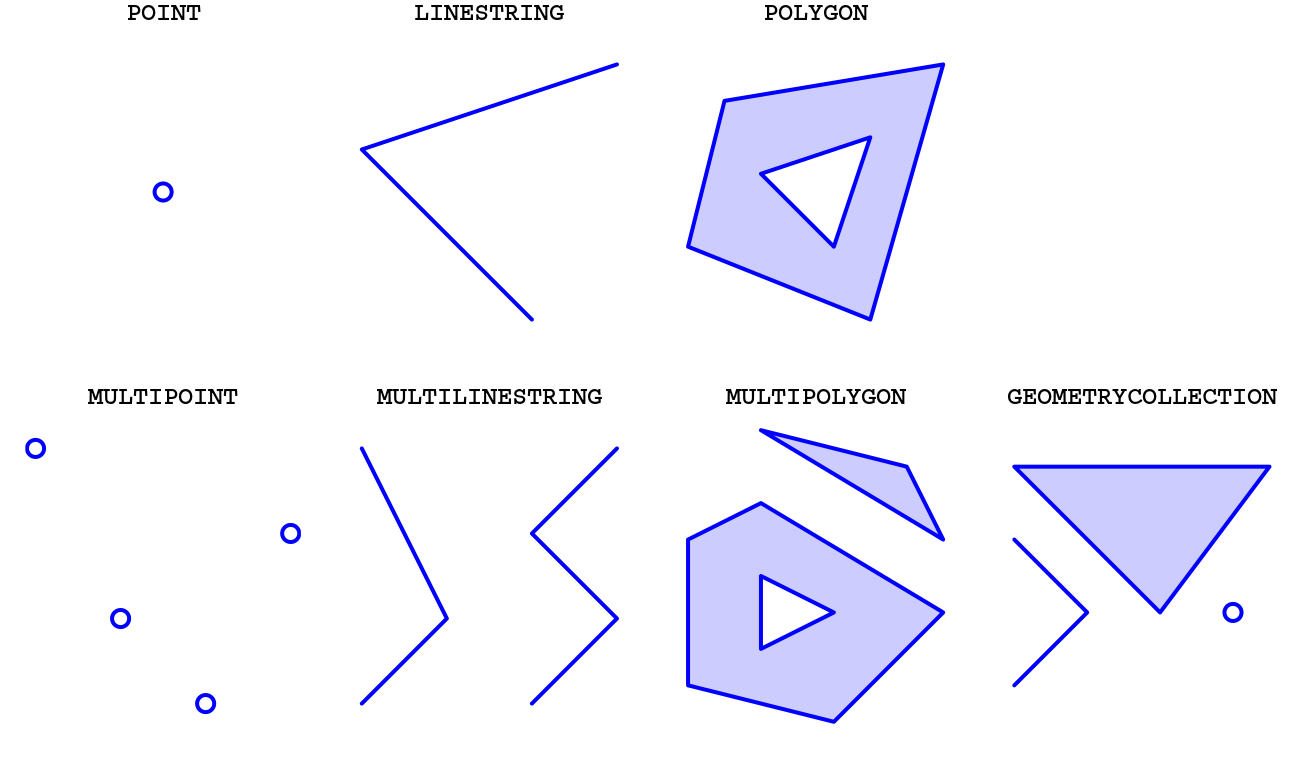

The seven most commonly used geometry types is displayed in Figure 7.8.

Figure 7.8: Simple feature geometry (sfg) types in package sf

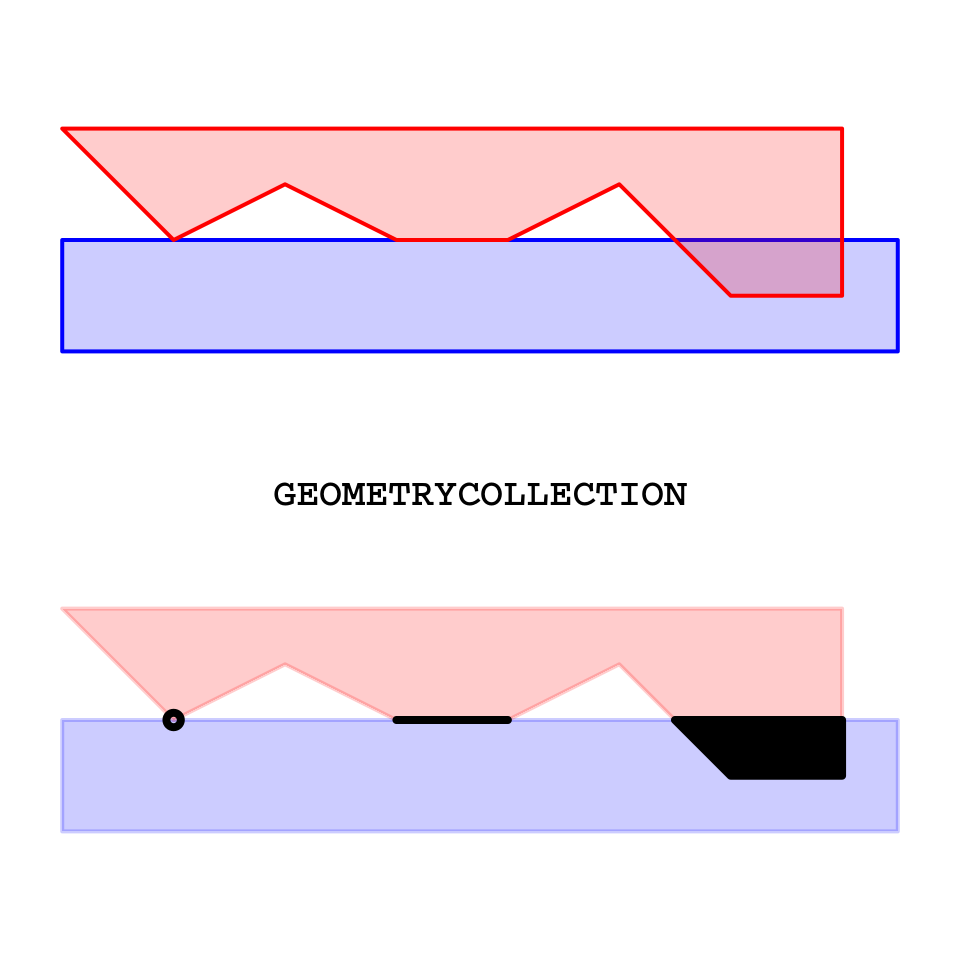

The GEOMETRYCOLLECTION is more rarely used and more difficult to work with. You may wonder why does it even exist. One of the reasons is that some spatial operations may produce a mixture of geometry types (Figure 7.9).

Figure 7.9: Intersection between two polygons may yield a GEOMETRYCOLLECTION

For example, we can create a point geometry object named pnt1, representing a POINT geometry, using the st_point function:

Printing the object in the console gives the WKT representation:

Note the class definition of an sfg (geometry) object is actually composed of three parts:

XY—The dimensions type (XY,XYZ,XYMorXYZM)POINT—The geometry type (POINT,MULTIPOLYGON, etc.)sfg—The general class (sfg= Simple Feature Geometry)

For example, the pnt1 object has geometry POINT and dimensions XY:

Here is another example of creating an sfg object. This time, we are creating a POLYGON with st_polygon. (We learn about list in Chapter 11).

The polygon is displayed in Figure 7.10:

Figure 7.10: An sfg object of type POLYGON

Another POLYGON:

The second polygon is shown in Figure 7.11.

Figure 7.11: Another sfg object of type POLYGON

The c function combines sfg geometries:

ab

## MULTIPOLYGON (((0 0, 0 -1, 7.5 -1, 7.5 0, 0 0)), ((0 1, 1 0, 2 0.5, 3 0, 4 0, 5 0.5, 6 -0.5, 7 -0.5, 7 1, 0 1)))What type of geometry is

c(a, b, pnt1)?

The multipolygon we created is shown in Figure 7.12:

Figure 7.12: An sfg object of type MULTIPOLYGON

A new geometry can be calculated applying various functions on an existing one(s). For example, the following example calculates the intersection of a and b. (We learn about st_intersection in Chapter 8.

The result happens to be a GEOMETRYCOLLECTION, as discussed above:

i

## GEOMETRYCOLLECTION (POINT (1 0), LINESTRING (4 0, 3 0), POLYGON ((5.5 0, 7 0, 7 -0.5, 6 -0.5, 5.5 0)))Figure 7.13 displays the GEOMETRYCOLLECTION:

Figure 7.13: An sfg object of type GEOMETRYCOLLECTION

7.2.2 Geometry column (sfc)

Let’s create a second point geometry named pnt2, representing a different point:

Geometry objects (sfg) can be collected into a geometry column (sfc) object. This is done with function st_sfc.

Geometry column objects contain a Coordinate Reference System (CRS) definition, specified with the crs parameter of function st_sfc. Two types of CRS definitions are accepted:

- An EPSG code (e.g.,

4326) - A WKT definition

Let’s combine the two POINT geometries pnt1 and pnt2 into a geometry column (sfc) object named geom:

Here is a summary of the resulting geometry column:

7.2.3 Layer (sf)

A geometry column (sfc) can be combined with non-spatial columns, or attributes, resulting in a layer (sf) object. In our case, the two points in the sfc geometry column geom represent the location of the two railway stations in Beer-Sheva. Let’s create a data.frame with:

- A

towncolumn specifying town name - A

stationcolumn specifying station name

Creating the attribute table:

dat = data.frame(

town = c("Beer-Sheva", "Beer-Sheva"),

station = c("North", "Center"),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)Note that the order of rows in the attribute table must match the order of the geometries!

Now we can combine the attribute table (data.frame) and the geometry column (sfc) to get a layer (sf), using function st_sf:

layer = st_sf(dat, geom)

layer

## Simple feature collection with 2 features and 2 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 34.79844 ymin: 31.24329 xmax: 34.81283 ymax: 31.26028

## geographic CRS: WGS 84

## town station geom

## 1 Beer-Sheva North POINT (34.81283 31.26028)

## 2 Beer-Sheva Center POINT (34.79844 31.24329)7.2.4 Interactive mapping with mapview

Function mapview is useful for inspecting vector layers:

7.3 Extracting layer components

In Section 7.2 we:

- Started from raw coordinates

- Convered them to geometry objects (

sfg) - Combined the geometries to a geometry column (

sfc) - Added attributes to the geometry column to get a layer (

sf)

which can be summarized as: coordinates → sfg → sfc → sf.

Sometimes we are interested in the opposite process. We may need to extract the simpler components (geometry, attributes, coordinates) from an existing layer:

sf→ geometry column (sfc)sf→ attributes (data.frame)sf→ coordinates (matrix)

The geometry column (sfc) component can be extracted from an sf layer object using function st_geometry:

st_geometry(layer)

## Geometry set for 2 features

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 34.79844 ymin: 31.24329 xmax: 34.81283 ymax: 31.26028

## geographic CRS: WGS 84

## POINT (34.81283 31.26028)

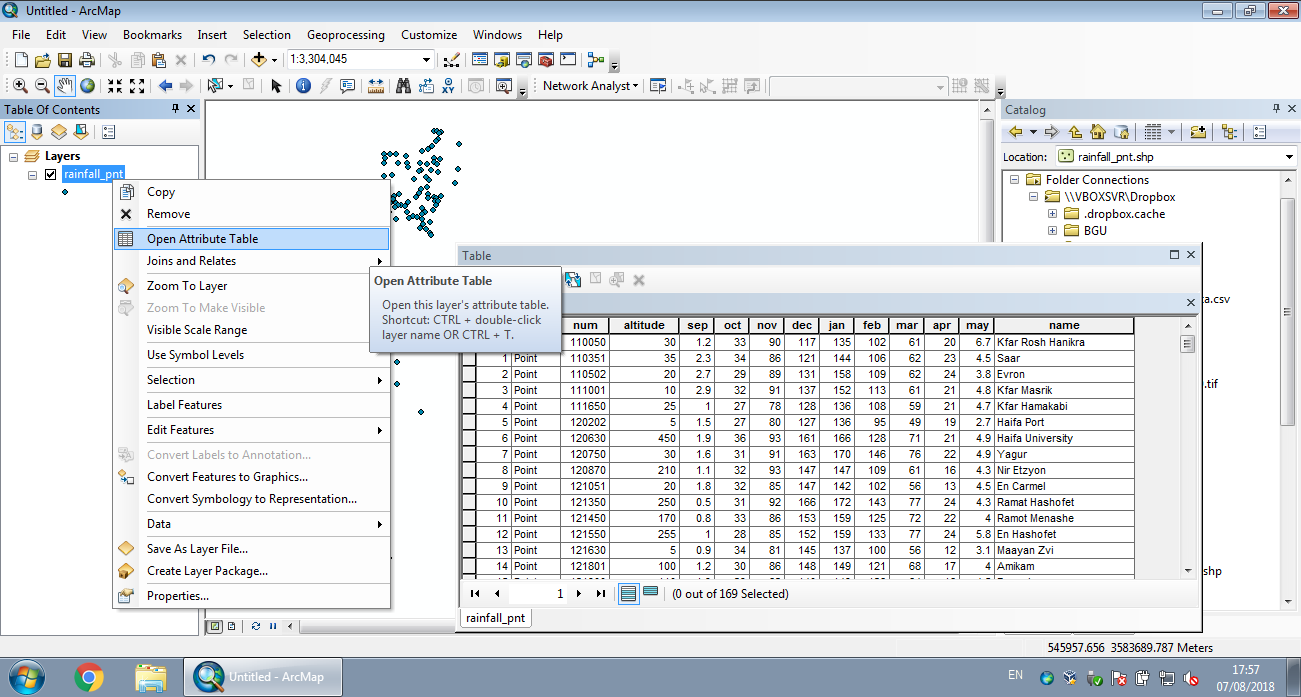

## POINT (34.79844 31.24329)The non-spatial columns of an sf layer, i.e., the attribute table, can be extracted from an sf object using function st_drop_geometry:

This is analogous to opening an attribute table of a vector layer in GIS software (Figure 7.14).

Figure 7.14: Attribute table in ArcGIS

The coordinates of sf, sfc or sfg objects can be obtained with function st_coordinates. The coordinates are returned as a matrix:

7.4 Creating point layer from table

A common way of creating a point layer is to transform a table which has X and Y coordinate columns. Function st_as_sf can transform a table (data.frame) into a point layer (sf). In st_as_sf we specify:

x—Thedata.frameto be convertedcoords—Columns names with the coordinates (X, Y)crs—The CRS (NAif left unspecified)

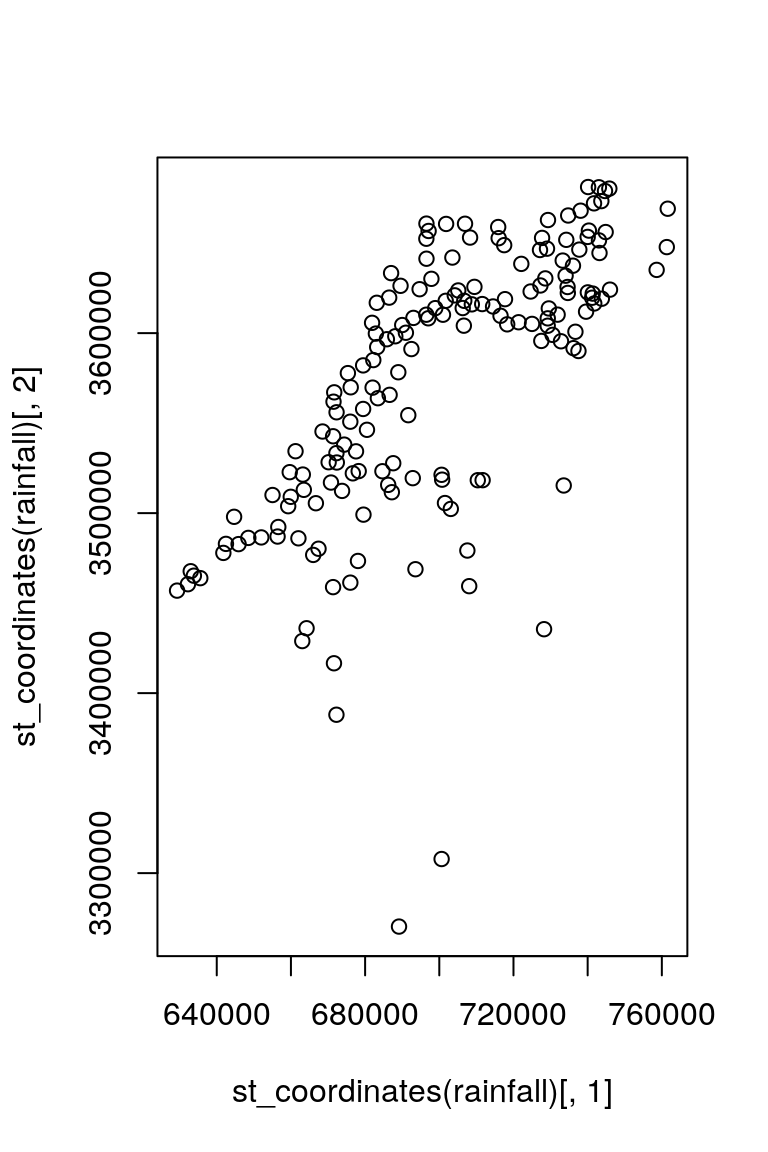

Let’s take the rainfall.csv table as an example. This table contains UTM 36N coordinates in the columns named x_utm and y_utm:

The table can be converted to an sf layer using st_as_sf as follows:

Note:

- The order of

coordscolumn names corresponds to X-Y! 32636is the EPSG code of the UTM 36N projection (Table 7.4)

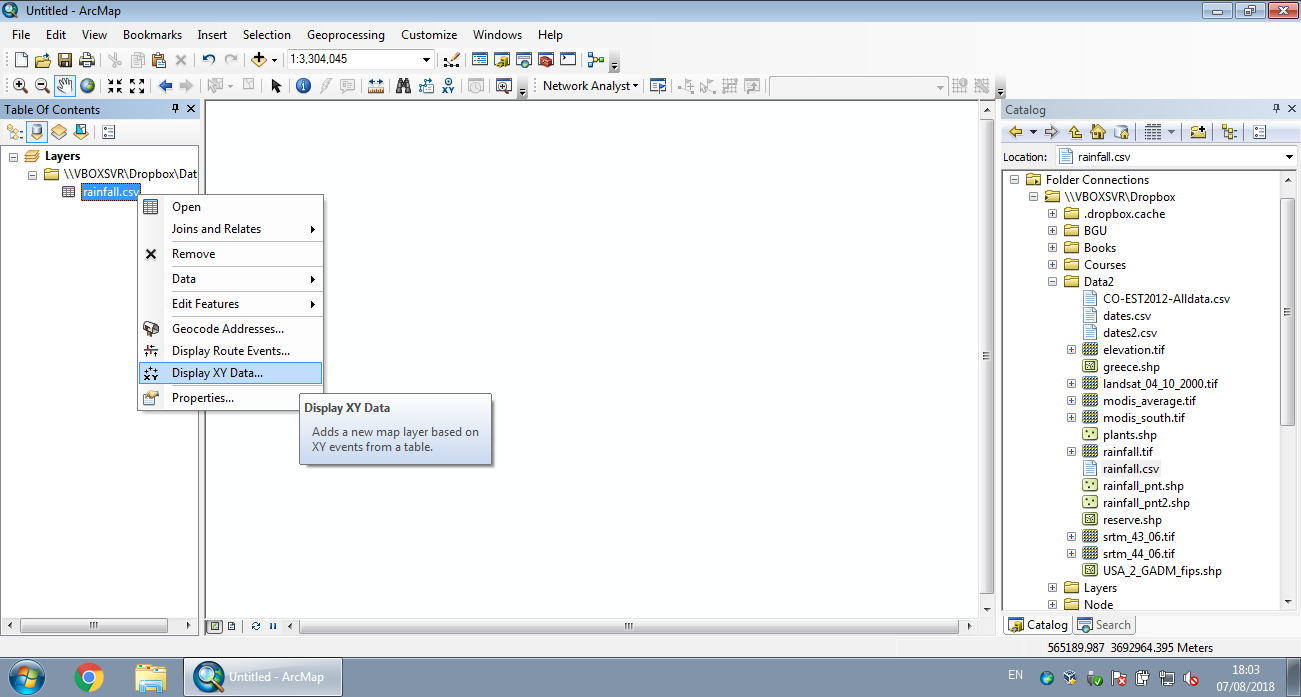

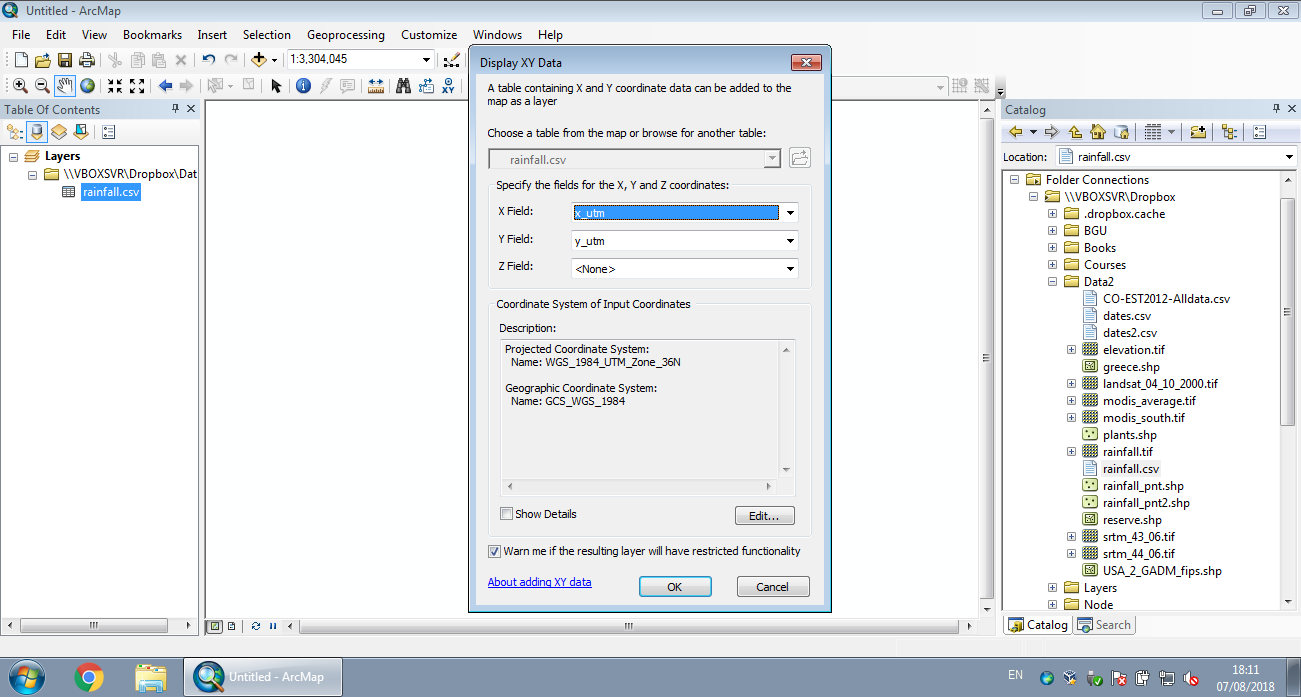

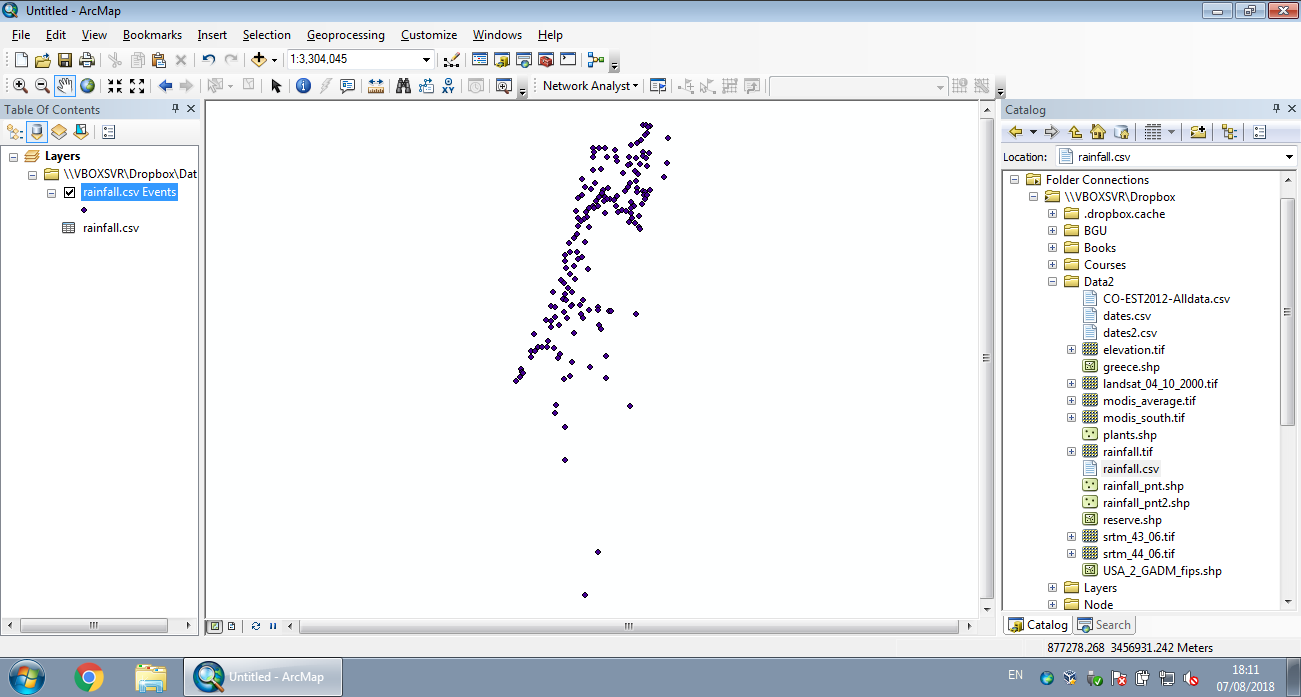

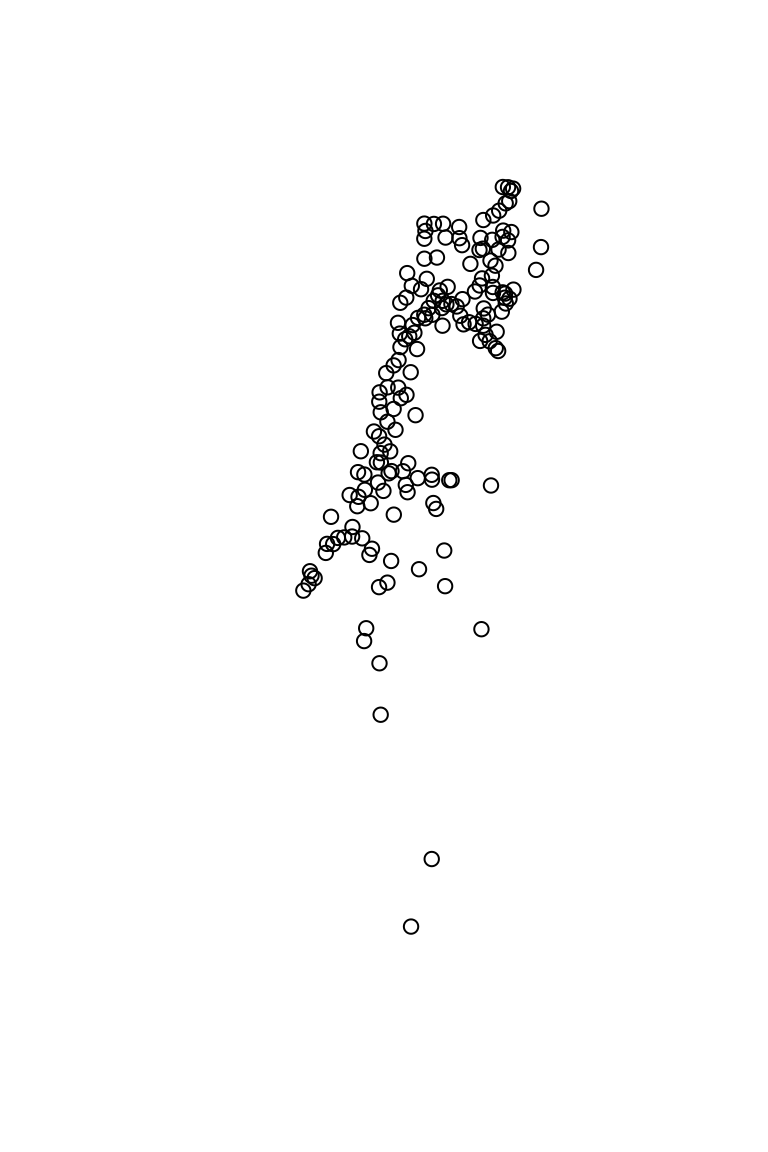

The analogous operation in ArcGIS is the Display XY Data menu (Figures 7.15–7.17).

Figure 7.15: Displaying XY data from CSV in ArcGIS (Step 1)

Figure 7.16: Displaying XY data from CSV in ArcGIS (Step 2)

Figure 7.17: Displaying XY data from CSV in ArcGIS (Step 3)

Here is the resulting sf layer:

rainfall

## Simple feature collection with 169 features and 12 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 629301.4 ymin: 3270290 xmax: 761589.2 ymax: 3681163

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## First 10 features:

## num altitude sep oct nov dec jan feb mar apr may name

## 1 110050 30 1.2 33 90 117 135 102 61 20 6.7 Kfar Rosh Hanikra

## 2 110351 35 2.3 34 86 121 144 106 62 23 4.5 Saar

## 3 110502 20 2.7 29 89 131 158 109 62 24 3.8 Evron

## 4 111001 10 2.9 32 91 137 152 113 61 21 4.8 Kfar Masrik

## 5 111650 25 1.0 27 78 128 136 108 59 21 4.7 Kfar Hamakabi

## 6 120202 5 1.5 27 80 127 136 95 49 19 2.7 Haifa Port

## 7 120630 450 1.9 36 93 161 166 128 71 21 4.9 Haifa University

## 8 120750 30 1.6 31 91 163 170 146 76 22 4.9 Yagur

## 9 120870 210 1.1 32 93 147 147 109 61 16 4.3 Nir Etzyon

## 10 121051 20 1.8 32 85 147 142 102 56 13 4.5 En Carmel

## geometry

## 1 POINT (696533.1 3660837)

## 2 POINT (697119.1 3656748)

## 3 POINT (696509.3 3652434)

## 4 POINT (696541.7 3641332)

## 5 POINT (697875.3 3630156)

## 6 POINT (687006.2 3633330)

## 7 POINT (689553.7 3626282)

## 8 POINT (694694.5 3624388)

## 9 POINT (686489.5 3619716)

## 10 POINT (683148.4 3616846)7.5 sf layer properties

7.5.1 Dimensions

An sf layer is basically a special type of data.frame, where one of the columns is a special geometry column. Therefore, many of the functions we learned when working with data.frame tables (Chapter 4) also work on sf layers.

For example, we can get the number of rows / features with nrow:

the number of columns (including geometry column) with ncol:

or both with dim:

What is the result of

st_geometry(rainfall)?st_drop_geometry(rainfall)?

7.5.2 Spatial properties

The st_bbox function returns the bounding box coordinates, just like for stars objects (Section 5.3.8.3):

The st_crs function returns the Coordinate Reference System (CRS), also the same way as for stars objects (Section 5.3.8.3):

st_crs(rainfall)

## Coordinate Reference System:

## User input: EPSG:32636

## wkt:

## PROJCRS["WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N",

## BASEGEOGCRS["WGS 84",

## DATUM["World Geodetic System 1984",

## ELLIPSOID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,

## LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]]],

## PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,

## ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

## ID["EPSG",4326]],

## CONVERSION["UTM zone 36N",

## METHOD["Transverse Mercator",

## ID["EPSG",9807]],

## PARAMETER["Latitude of natural origin",0,

## ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433],

## ID["EPSG",8801]],

## PARAMETER["Longitude of natural origin",33,

## ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433],

## ID["EPSG",8802]],

## PARAMETER["Scale factor at natural origin",0.9996,

## SCALEUNIT["unity",1],

## ID["EPSG",8805]],

## PARAMETER["False easting",500000,

## LENGTHUNIT["metre",1],

## ID["EPSG",8806]],

## PARAMETER["False northing",0,

## LENGTHUNIT["metre",1],

## ID["EPSG",8807]]],

## CS[Cartesian,2],

## AXIS["(E)",east,

## ORDER[1],

## LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]],

## AXIS["(N)",north,

## ORDER[2],

## LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]],

## USAGE[

## SCOPE["unknown"],

## AREA["World - N hemisphere - 30°E to 36°E - by country"],

## BBOX[0,30,84,36]],

## ID["EPSG",32636]]An interactive map, showing the spatial locations of the rainfall stations, can be created using mapview. Here, we are using the additional zcol parameter to choose which attribute will be used for the color scale:

Question: what is the difference between the two plots in Figure 7.18, created using the following expressions?

Figure 7.18: Two plots

7.6 Subsetting based on attributes

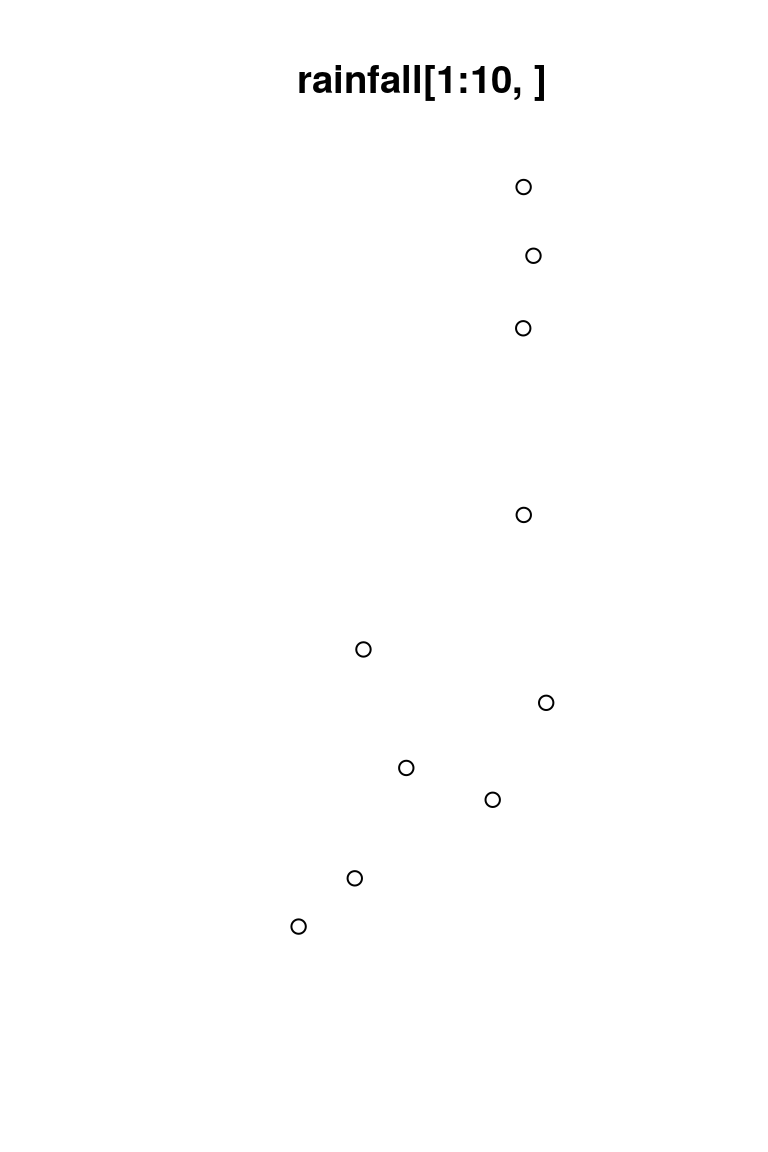

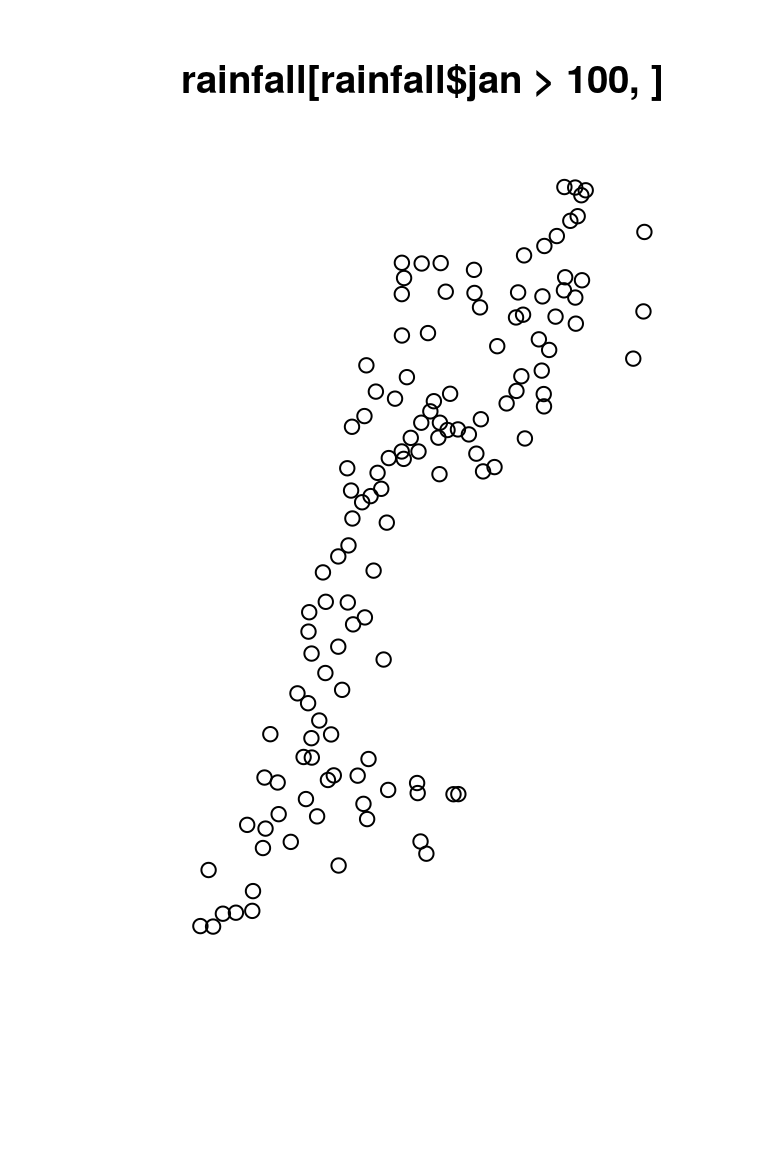

Subsetting of features in an sf vector layer is exactly the same as filtering rows in a data.frame. Remember: an sf layer is a data.frame. For example, the following expressions subset the rainfall layer:

Which meteorological stations are being selected in the last two expressions?

Figure 7.19 shows the resulting subsets:

plot(

st_geometry(rainfall[1:10, ]),

main = "rainfall[1:10, ]"

)

plot(

st_geometry(rainfall[rainfall$jan > 100, ]),

main = "rainfall[rainfall$jan > 100, ]"

)

Figure 7.19: Subsets of the rainfall layer

Note that the geometry column “sticks” to the subset, by default, even if we do not select it, so that the resulting subset remains an sf object:

rainfall[1:2, c("jan", "feb")]

## Simple feature collection with 2 features and 2 fields

## geometry type: POINT

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 696533.1 ymin: 3656748 xmax: 697119.1 ymax: 3660837

## projected CRS: WGS 84 / UTM zone 36N

## jan feb geometry

## 1 135 102 POINT (696533.1 3660837)

## 2 144 106 POINT (697119.1 3656748)In case we need to omit the geometry column and get a data.frame, we can apply st_drop_geometry (Section 7.3) on the subset:

7.7 Reading and writing vector layers

7.7.1 Reading vector layers

In addition to creating from scratch (Section 7.2) and transforming a table to point layer (Section 7.4), often we want to read existing vector layers from a file or from a spatial database (Section 7.1.2)38. This can be done with the st_read function.

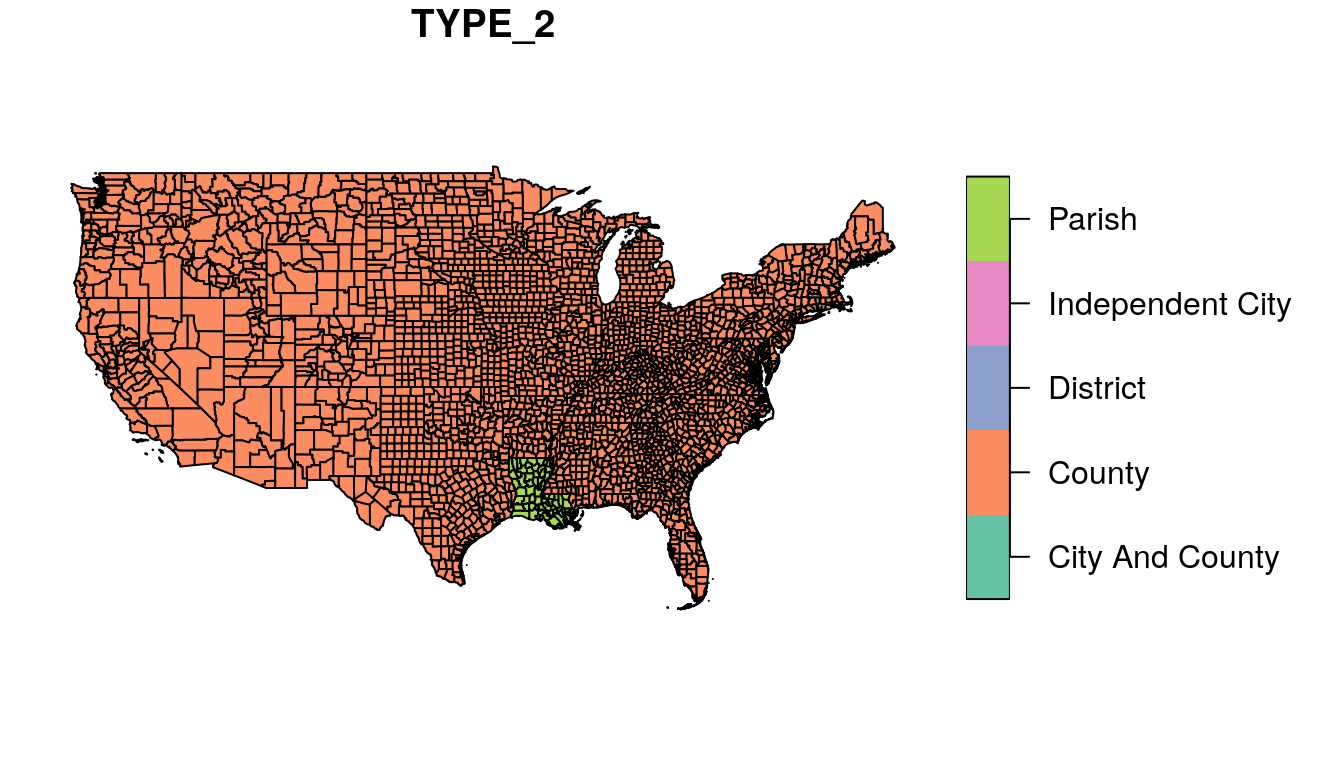

For example, we will read the Shapefile of US county boundaries, named USA_2_GADM_fips.shp, from the course materials. In case the Shapefile is located in the working directory, we only need to specify the name of the .shp file. We can also specify stringsAsFactors=FALSE to avoid conversion of character to factor (Section 4.4.1):

Let’s also read a GeoJSON file with the location of three particular airports in New Mexico:

7.7.2 Writing vector layers

Writing an sf object to a file can be done with st_write. Before writing the rainfall layer back to disk, let’s calculate a new column called annual (Section 4.5):

m = c("sep", "oct", "nov", "dec", "jan", "feb", "mar", "apr", "may")

rainfall$annual = apply(st_drop_geometry(rainfall[, m]), 1, sum)In the last expression, why did we use

st_drop_geometry(rainfall[, m])as the first argument inapply, instead ofrainfall[, m]?

The sf object can be written to a Shapefile with st_write, as follows:

The format is automatically determined based on the .shp file extension. To overwrite an existing file, use delete_dsn=TRUE.

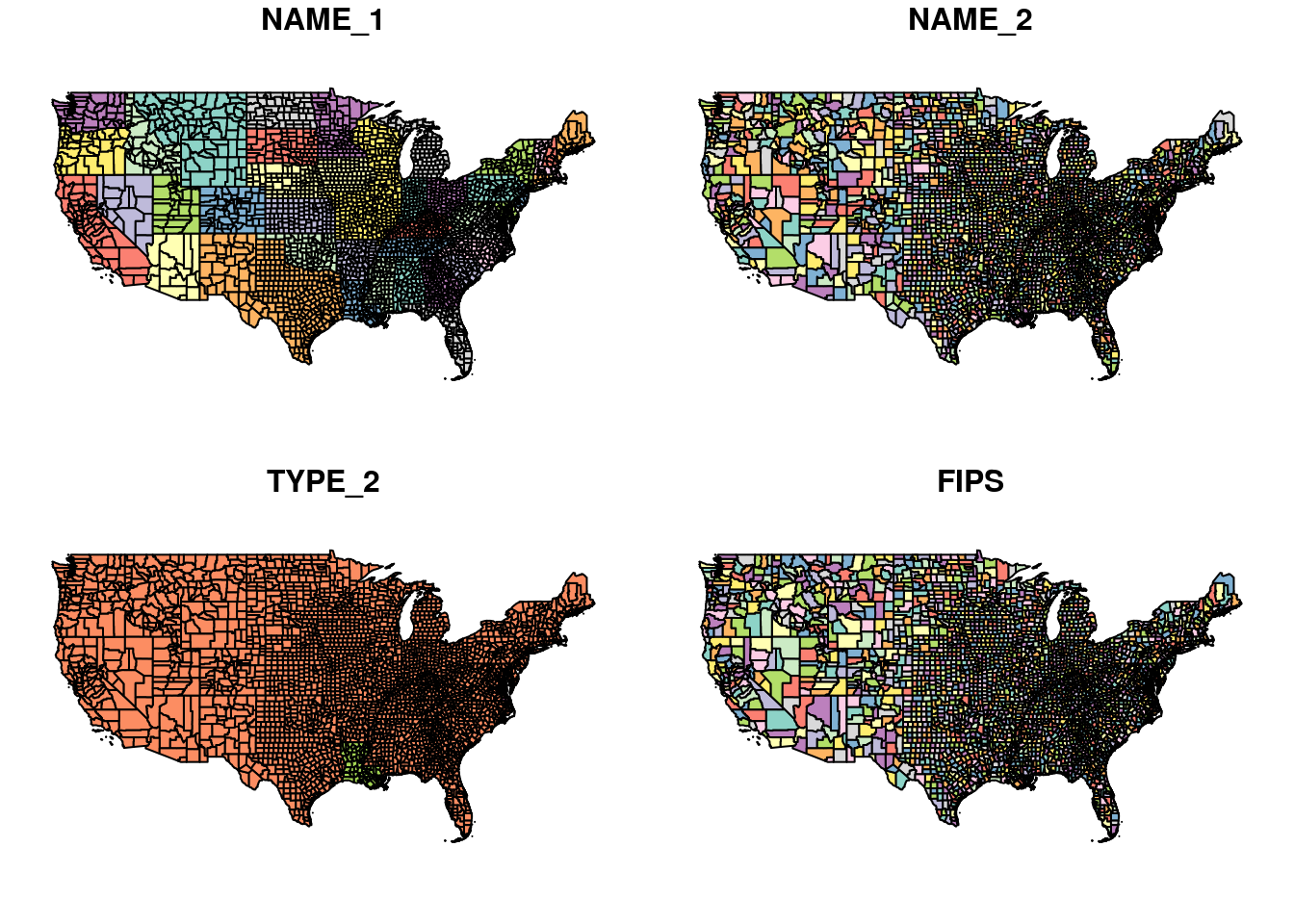

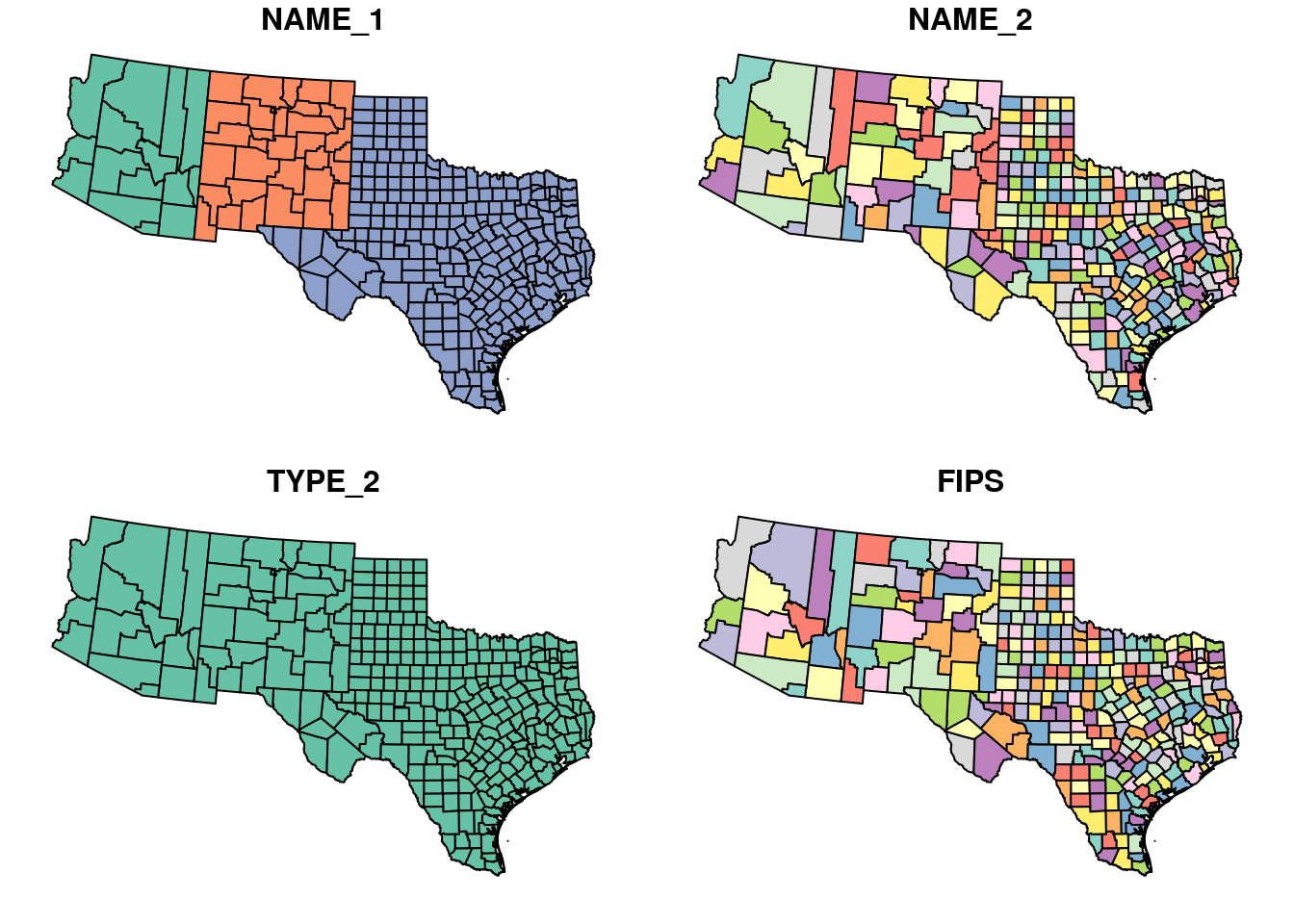

7.8 Basic plotting

When plotting an sf object with plot, we get multiple small maps—one map for each attribute. This can be useful to quickly examine the types of spatial variation in our data. For example (Figure 7.20):

Figure 7.20: Plot of sf object

Plotting a single attribute adds a legend (Figure 7.21). The key.width and key.pos let us control the amount of space the legend takes and its placement, respectively:

Figure 7.21: Plot of sf object, single attribute with legend

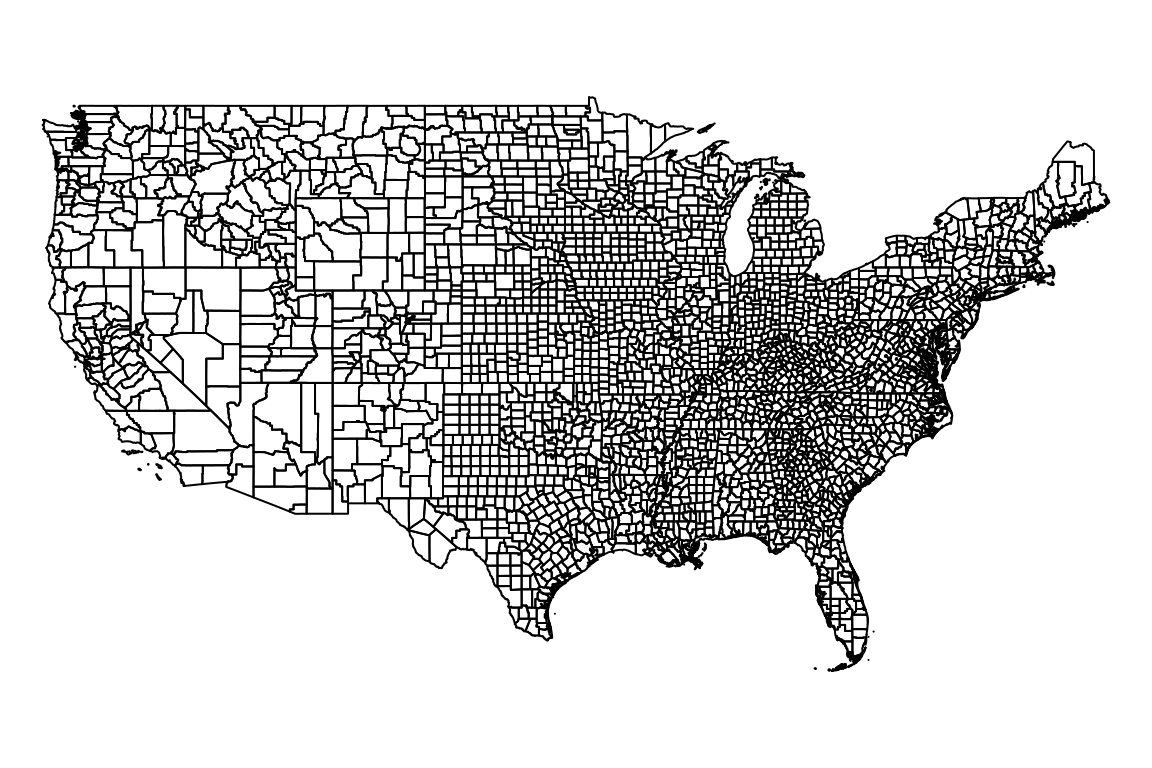

Plotting an sfc or an sfg object shows just the geometry (Figure 7.22):

Figure 7.22: Plot of sfc object

We can use graphical parameters to control the appearance of plotted geometries, such as:

col—Fill colorborder—Outline colorpch—Point shapecex—Point size

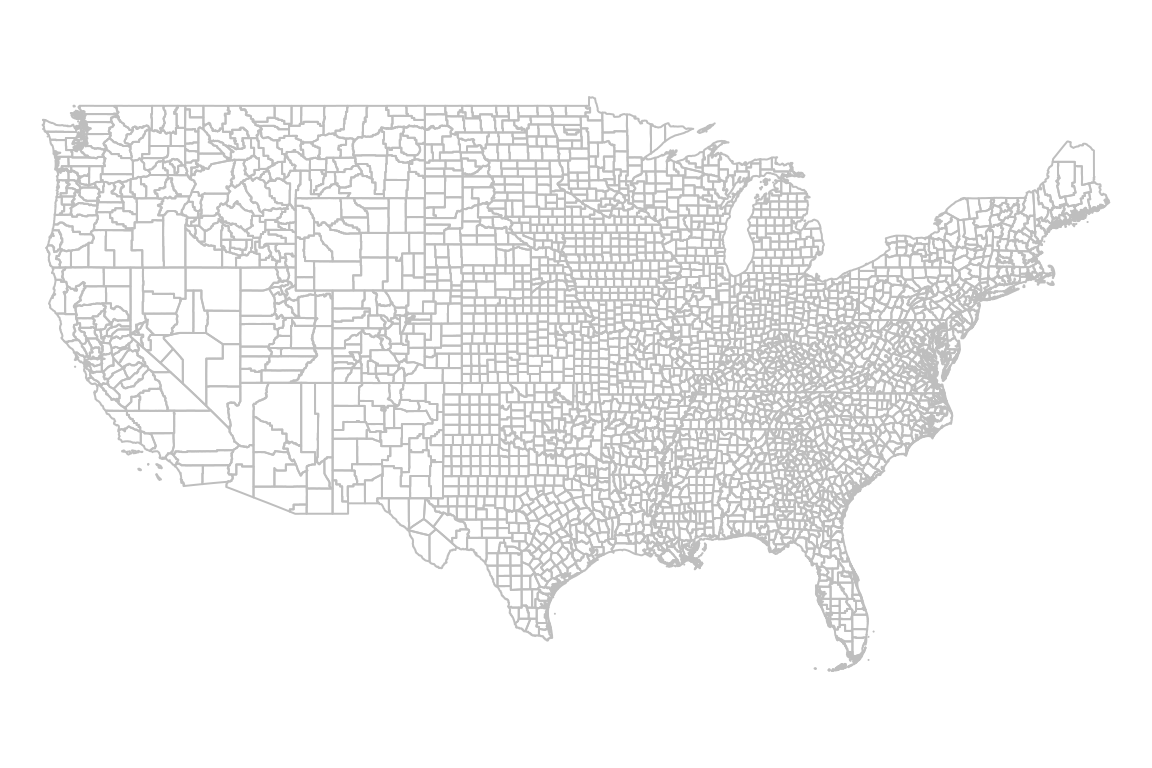

For example, the following expression draws county borders in grey (Figure 7.23):

Figure 7.23: Basic plot of sfc object

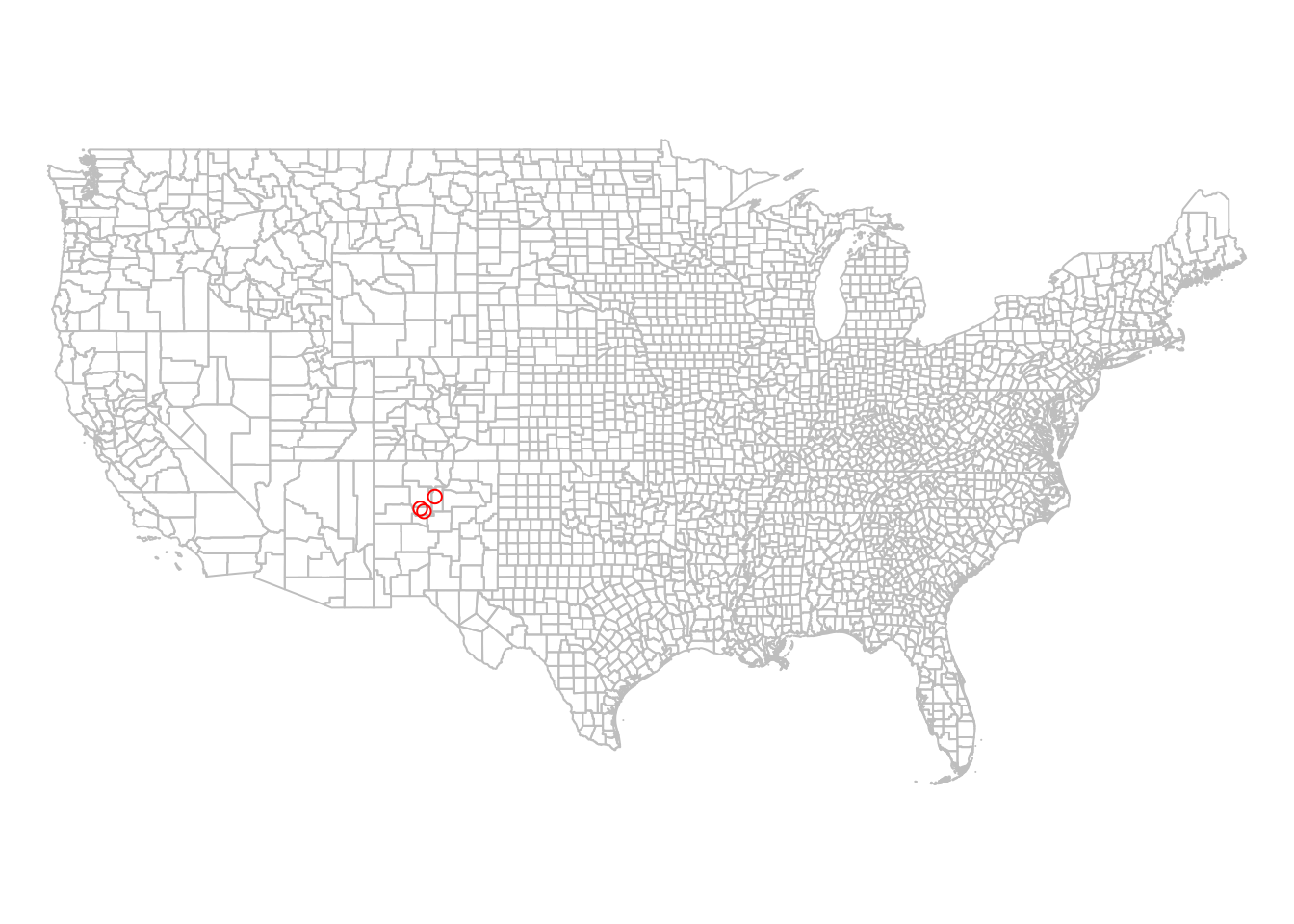

Additional vector layers can be drawn in an existing graphical window using add=TRUE. For example, the following expressions draw both county and airports geometries (Figure 7.24). Note how the second expression uses add=TRUE:

Figure 7.24: Using add=TRUE in plot

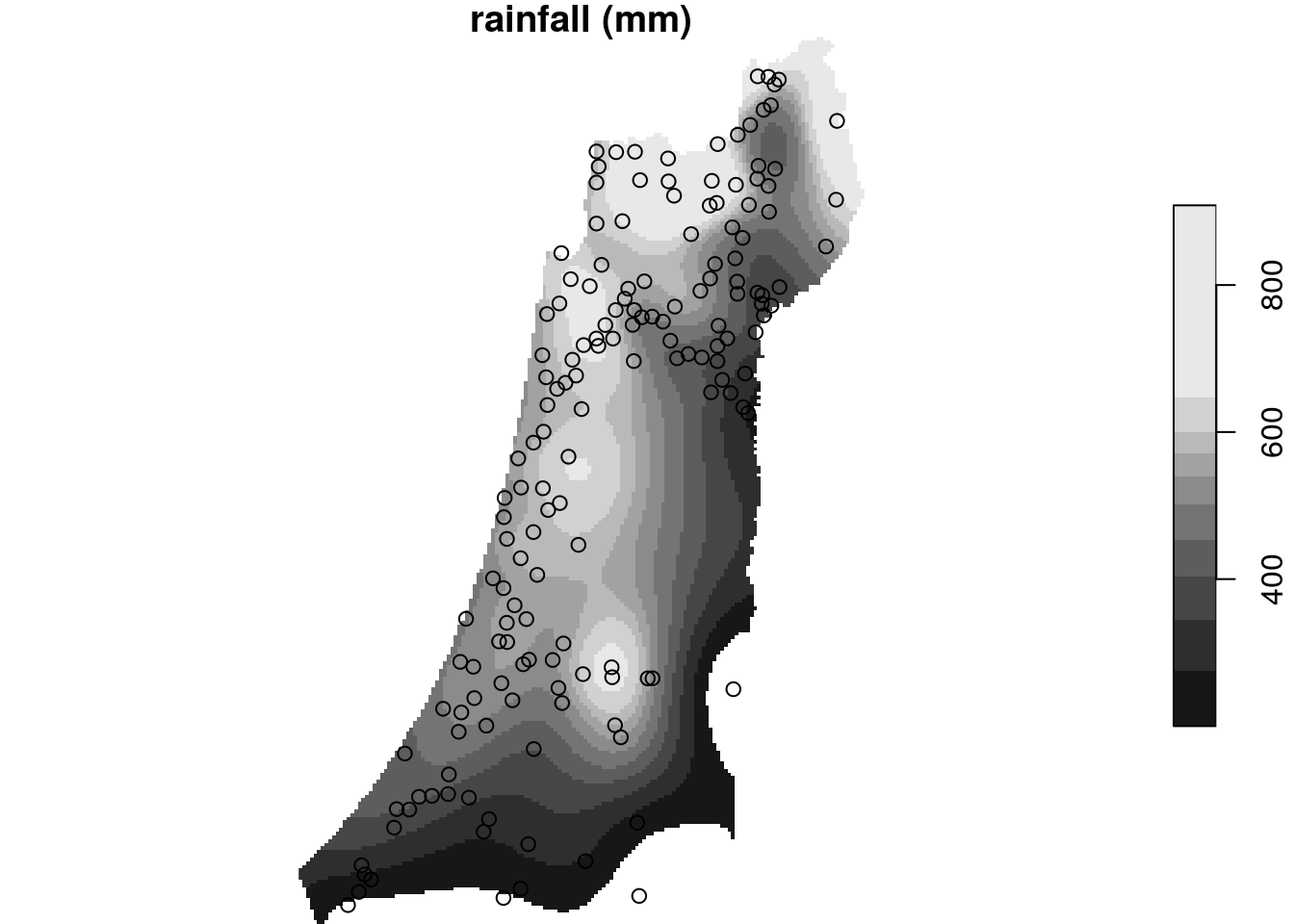

We can also use add=TRUE to combine sfg or sfc geometries with rasters in the same plot. For example, let’s plot the rainfall layer on top of the rainfall.tif raster, which is an interpolated rainfall surface we met in Chapter 1. First we will read the raster file:

and then plot (Figure 7.25):

Figure 7.25: sfc layer on top of a raster

Note that we need to use the additional argument reset=FALSE whenever we are adding more layers to a stars raster plot.

7.9 Coordinate Reference Systems (CRS)

A Coordinate Reference System (CRS) defines how the coordinates in the data relate to the surface of the Earth. There are two main types of CRS:

- Geographic—longitude and latitude, in degrees

- Projected—implying flat surface, usually in units of true distance (e.g., meters)

In geographic CRS, the units of measurement are degrees (longitude and latitude). In projected CRS, the units of measurement usually refer to real distances, commonly meters.

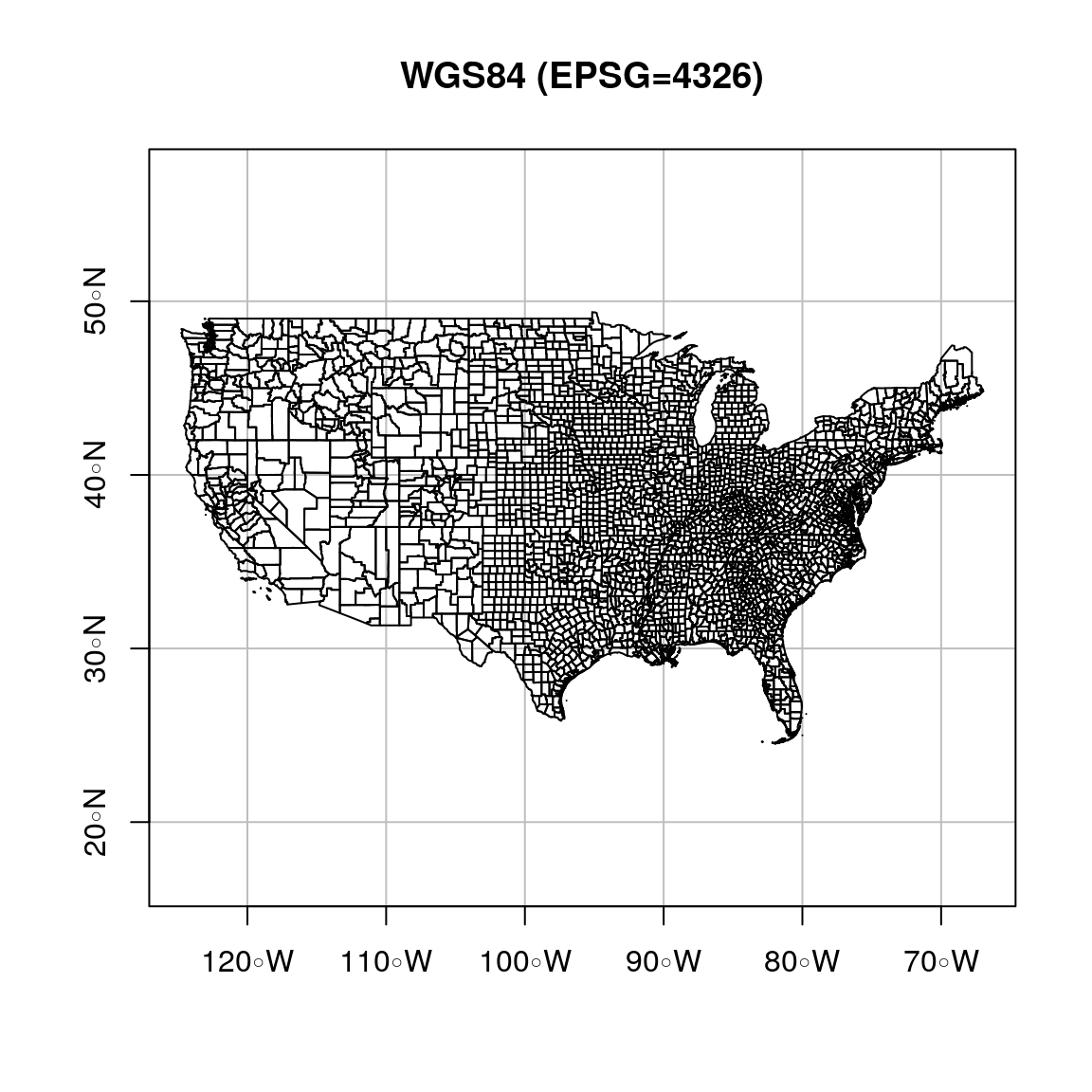

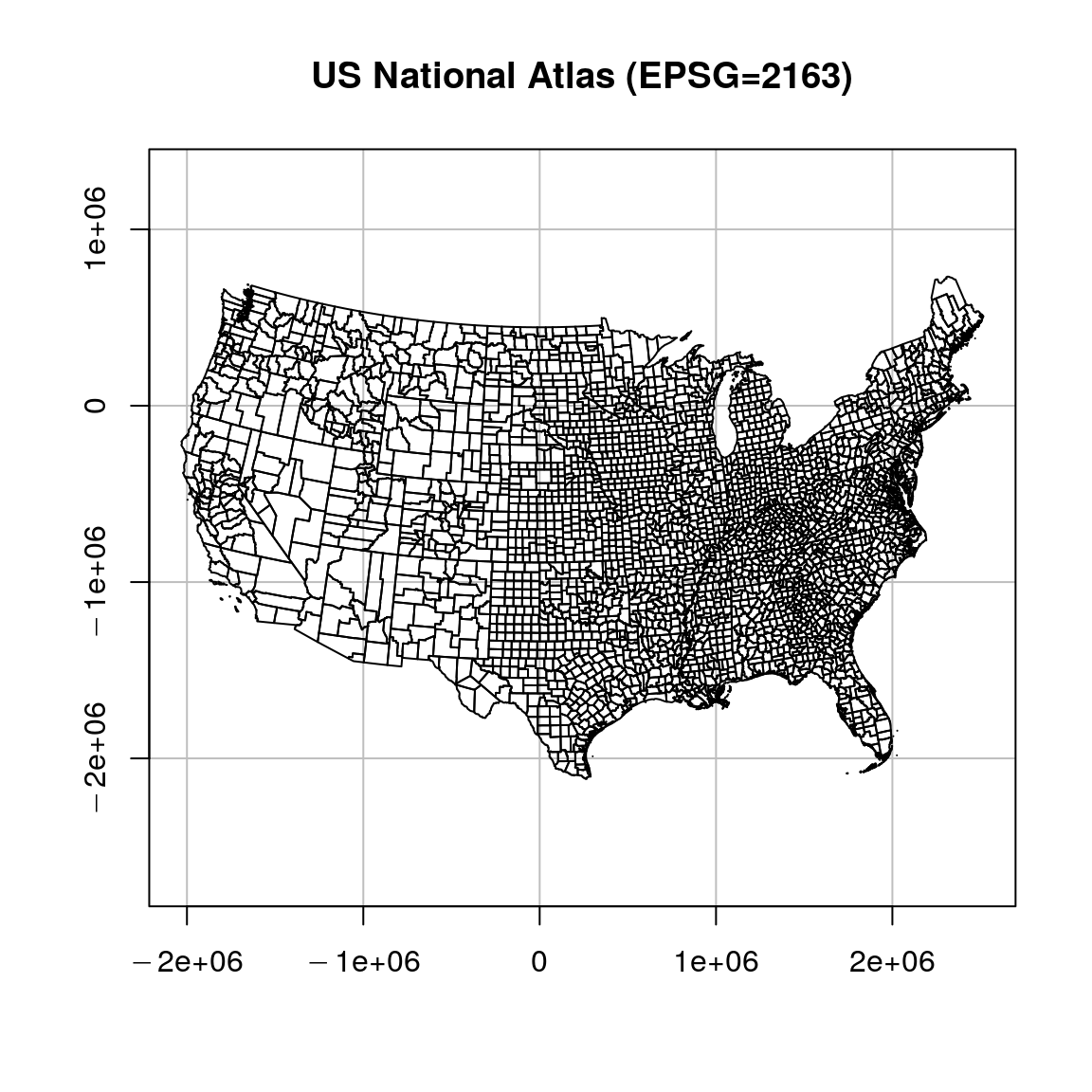

For example, Figure 7.26 shows the same polygonal layer (U.S. counties) in two different projection. On the left, the county layer is in the WGS84 geographic projection. Indeed, we can see that the axes are given in degrees of longitude and latitude. For example, we can see how the nothern border of U.S. follows the 49° latitude line. On the right, the same layer is displayed in the US National Atlas projection, where units are arbitrary but reflect true distance (meters). For example, the distance between every two consecutive grid lines is 1,000,000 meters or 1,000 kilometers.

Figure 7.26: US counties in WGS84 and US Atlas projections

7.10 Vector layer reprojection

Reprojection is an important part of spatial analysis workflow since as we often need to:

- Transform several layers into the same projection

- Switch between un-projected and projected data

A vector layer can be reprojected with st_transform. The st_transform function has two important parameters:

x—The layer to be reprojectedcrs—The target CRS

Question: why don’t we need to specify the origin CRS?

The CRS can be specified in one of two ways:

- An EPSG code (e.g.,

4326) - A WKT definition

For example, Figure 7.27 shows a map of the US in four different projections.

![Map of the US using different projections^[https://datacarpentry.org/r-raster-vector-geospatial/09-vector-when-data-dont-line-up-crs/index.html]](images/lesson_07_projections.jpg)

Figure 7.27: Map of the US using different projections39

Where can we find EPSG codes and WKT definitions?

- The internet, such as http://spatialreference.org

- The

make_EPSGfunction from packagergdalin R

During the course we will encounter just five projections: WGS84, Sinusoidal, UTM 36N, ITM and US National Atlas (Table 7.4). We are going to specify them using EPSG code since it is easier.

| Name | Type | Area | Units | EPSG code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGS84 | Geographic | World | degrees | 4326 |

| Sinusoidal | Projected | World | meters | - |

| UTM 36N | Projected | Israel | meters | 32636 |

| ITM | Projected | Israel | meters | 2039 |

| US National Atlas | Projected | USA | meters | 2163 |

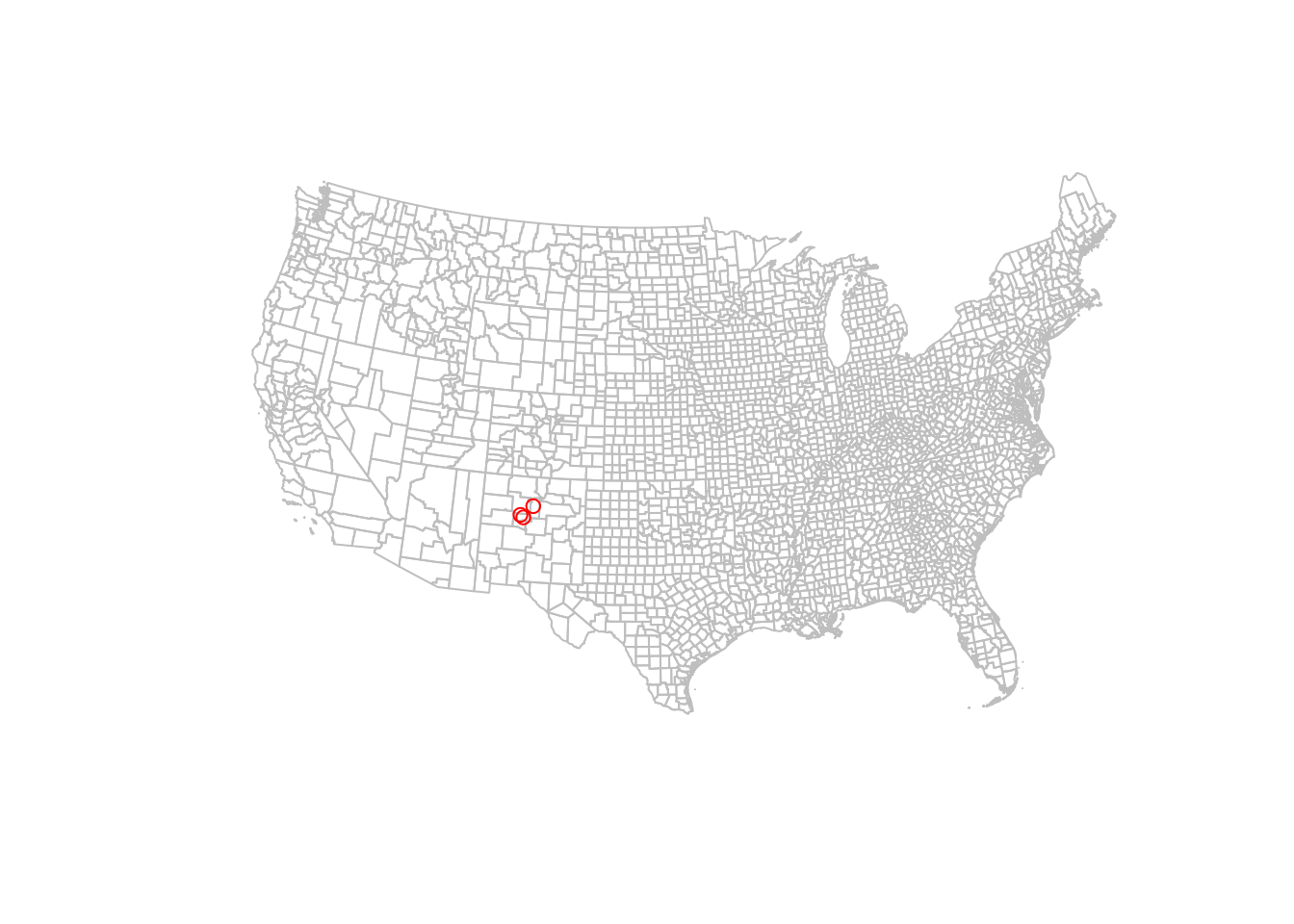

For example, in the following code section we are reprojecting both the county and airports layers. The target CRS is the US National Atlas Equal Area projection (EPSG code 2163):

The results are shown in Figure 7.28:

Figure 7.28: The county and airports layers in the US National Atlas Projection (EPSG=2163)

Examnining the layer coordinates shows they indeed change with reprojecton:

st_coordinates(st_transform(airports, 4326)) # WGS84

## X Y

## 1 -106.6169 35.04807

## 2 -106.7947 35.15559

## 3 -106.0892 35.61621st_coordinates(st_transform(airports, 2163)) # US National Atlas

## X Y

## 1 -603868.2 -1081605

## 2 -619184.5 -1068431

## 3 -551689.8 -1022366Create a subset of

countywith the counties of New-Mexico, Arizona and Texas only, and plot the result (Figure 7.29).

Figure 7.29: Subset of three states from the county layer

blog.revolutionanalytics.com/2015/07/the-network-structure-of-cran.html↩

https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sf/vignettes/sf1.html↩

For a complete list of vector formats that can be read with

st_read, runst_drivers(what="vector").↩https://datacarpentry.org/r-raster-vector-geospatial/09-vector-when-data-dont-line-up-crs/index.html↩